In Oslo, the street lamps are powered by renewables. To conserve energy, the smart lights dim when nobody is around. The Norwegian capital, like the rest of the country, is proud of its exceptional green credentials. Its public transportation system too is powered entirely by renewable energy. Two thirds of new cars sold in the city are electric. There’s even a highway for bees.

There’s just one problem. Much of the environmental innovation that Norway is so proud of is financed by its oil money. Because Norway, apart from being a forward-thinking climate champion, is also a major fossil fuels exporter. And it plans to keep it that way for a long time to come.

Norway isn’t the only country preaching sustainability while simultaneously cashing in on the very thing that is causing climate change. The UK is hosting a major climate summit later this year. At the same time, it is contemplating opening a new coal mine. Canada, a self-proclaimed climate leader, is pouring tax dollars into a doomed oil pipeline project.

The math doesn’t add up

Many countries produce fossil fuels despite committing to combat climate change. But Canada, Norway and the UK stand out because they are doing that while positioning themselves as climate champions.

“The UK is leading the world in the fight against climate change,” a spokesperson from the UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, told CNN in an email. “We were the first major economy to legislate for net zero emissions by 2050, and have cut emissions by 43% since 1990 – the best in the G7.”

The UK government can make these claims, because under international agreements, each country is only responsible for greenhouse gas emissions produced within its territory. That means the UK, Canada, Norway and others don’t need to worry about the emissions caused by the burning of their oil, gas and coal in other places around the world.

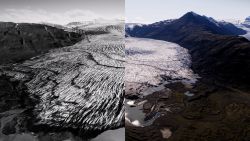

Burning fossil fuels emits CO2, which traps solar radiation in the atmosphere, just like glass traps heat in a greenhouse. This causes temperatures to rise, which in turn drives more extreme weather, ice melt and sea level rise.

It’s a simple equation: The more fossil fuels we burn, the more CO2 is released into the atmosphere and the larger the greenhouse effect.

The goal of the Paris Climate Accord is to limit warming to below 2 degrees Celsius and as close as possible to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. To achieve that, the world needs to cut fossil fuel production by roughly 6% per year between 2020 and 2030. Yet current projections show an annual increase of 2%.

“We just can’t afford to burn the majority of existing fossil fuel reserves in order to stay below 1.5 degrees Celsius,” said Ploy Achakulwisut, a scientist at the Stockholm Environment Institute.

Interactive: The pandemic gave the world an opportunity to fix the climate crisis

Climate scientists have estimated the amount of greenhouse gases we can still add to the atmosphere without breaching the critical threshold of 1.5 degrees. At the start of 2018, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated this so-called carbon budget to be around 420 gigatons (billion tons) of CO2 for a two-in-three chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees.

A more recent estimate published in the journal Nature earlier this year puts the figure at a range from 230 gigatons for a two-in-three chance of meeting the target to 670 gigatons for a two-in-three chance of missing it.

The world produced roughly 34 gigatons of CO2 last year, which means the remaining carbon budget could last for just over six years, unless emissions start declining fast.

Canada, the UK and Norway have all set ambitious targets. The UK and Canada pledged to reduce their territorial emissions to net zero by 2050. Norway wants to be carbon neutral by 2030. The “net” zero means that if they can’t eliminate all emissions completely, they can make up for the difference by removing carbon from the atmosphere, for example by planting more trees.

Professor Niklas Höhne, founding partner at the NewClimate Institute, a climate think tank, told CNN the decision to focus on territorial emissions goes back to the early days of climate negotiations. “There was a long discussion on whether to do it this way and this agreement was reached and it’s not covering the issue of exports, or the issues of consumption of goods that are produced elsewhere … and I agree, it doesn’t 100% make sense,” he said.

It makes a huge difference. Norway’s annual domestic emissions reached around 53 million tons in 2017, according to its statistical office. The emissions from the oil and gas Norway sold abroad reached roughly 470 million tons in 2017, according to the UN Emission Gap Report.

Norway’s minister of climate and environment, Sveinung Rotevatn, told CNN in a statement that the country’s commitments are based on territorial climate targets. “Emissions related to the consumption of exported oil and gas products in other countries are covered by the importers’ emission accounts and targets,” he said. Asked about the country’s oil and gas export plans, he said “Norway strongly supports a transition from the use and production of fossil energy to renewable energy.”

The carbon lock-in

Andrew Grant, the head of climate, energy and industry research at Carbon Tracker, a think tank, points out that that many producers rely economically on revenues from fossil fuels. They know the world will need to wean itself off them soon, but no one wants to be the first one to get out.

“Everyone has reasons why they think it should be them that continues producing and no one else,” Grant told CNN. “In the Middle East, it’s because it’s very low cost, in Canada, they talk about their human rights record, in Norway, they talk about the low carbon intensity of their production, in the UK, it’s because we’ve got mature fields of infrastructure … in the USA, they were even saying they’re gonna export their molecules of freedom.”

Producing fossil fuels can be expensive and many governments argue that stopping now would be a waste of money, often public, already spent on existing projects and explorations.

Höhne said the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline that runs from Russia to Germany is a good example. “It’s 95% done. And people now argue whether we should do it or not and there’s a pressure to have it operating because people invested a lot of money into it. So now that it’s almost there, shouldn’t we just build it and then use it?” he said. “I say no. This is not Paris-compatible, we need less fossil fuel infrastructure and not more. This is not necessary and it’s actually counterproductive.”

Canada, Norway and the UK all plan to keep producing fossil fuels, investing in new projects and explorations.

According to Canada Energy Regulator, the country’s crude oil production is expected to keep increasing until 2039. Canada’s proven oil reserves stand at roughly 168 billion barrels, according to government data. If all of that is extracted and burned, it would add an estimated 72 gigatons of CO2 into the atmosphere, based on a calculation using IPCC’s figures for default carbon contents. That’s almost a third of the world’s remaining carbon budget. The Canadian government has not responded to repeated requests for comment.

If Norway also continues to drill as planned, the total emissions from its known oil and gas reserves will amount to roughly 15 gigatons of CO2, according to CICERO, a Norwegian climate research institute. That would eat up 6.5% of the remaining carbon budget for the whole world.

Meanwhile, the UK Oil and Gas Authority estimates that as of the end of 2019, UK petroleum reserves stood at 5.2 billion barrels, enough to continue production for two more decades. If that happens, subsequent combustion of these extracted fuels would add a further 2.2 gigatons of CO2 into the atmosphere. The UK as a whole produced 454 million tons of CO2 equivalent in 2019, the latest figures available. Its plan is to reduce this to 193 millionmillion tons of CO2 annually by 2033.

The numbers are estimates but they illustrate a major problem: National plans to cut emissions don’t add up to the global total needed.

Höhne said climate plans cannot stop at emission-cutting targets and should also set deadlines for phasing out internal combustion engines, reaching 100% renewables, and fossil fuels exit dates. “So far, only a few small producers have stopped permitting new fossil fuel sites, Denmark was one in the last few months, and that kind of a decision needs to happen in Norway and Canada and the US and UK as well.”

Public pressure

While the current international agreements do not prevent countries from exporting fossil fuels emissions elsewhere, there’s a new, powerful force that the governments need to think about: Voters.

Public opinion has shifted in recent years, with climate protesters flooding the streets. When the UK government green-lit a plan to build its first deep coal mine in 30 years in Cumbria, northwest England, earlier this year, the decision sparked a wave of protests, including a 10-day hunger strike by two teenage activists.

The mine was approved despite the UK’s commitment to stop burning coal by 2025, because it would produce high-quality metallurgical coal used to make steel. It’s a similar argument made by Australia and other coal producers: Coal is bad, but our coal is better.

“That’s one trend that you see across sectors that are going to be impacted by climate regulation,” said Edward Collins, the director of corporate lobbying at InfluenceMap, a think tank studying climate lobbying. “It’s the ‘We’re special and though we support your climate ambition, this project, you know, we need this because of any number of reasons like jobs or the economy,’ and every single sector makes these claims,” he added.

The UK Climate Change Committee (CCC), an independent government advisory body, estimated the Cumbria mine’s operation and coal production would emit around 9 million tons of CO2 every single year, and noted that metallurgical coal too is scheduled to be phased out in the UK by 2035.

James Hansen, one of the world’s leading climate scientists, has written a personal letter to Prime Minister Boris Johnson urging him to reconsider the plan and telling him he risks being “vilified” and “humiliated” by young people if the mine goes ahead.

The action forced Cumbria County Council, the local authority – which has previously approved the new mine three times – to make a U-turn earlier this month. It said it will now reassess the plan.