The Perseverance rover is the fifth robotic explorer sent by NASA to journey across the Martian surface, but it’s going to land in a spot that has never been attempted by the agency: Jezero Crater.

The crater is incredibly intriguing to scientists because it’s possible that life may have existed in an ancient lake that filled the crater 3.9 billion years ago. But it’s also a dangerous site full of hazards – especially when thinking about landing an SUV-size rover on the Martian surface.

While Mars may look like one big red frozen desert from space, the surface is incredibly varied and dotted with craters, canyons, mountains, glaciers and features that speak of its ancient past.

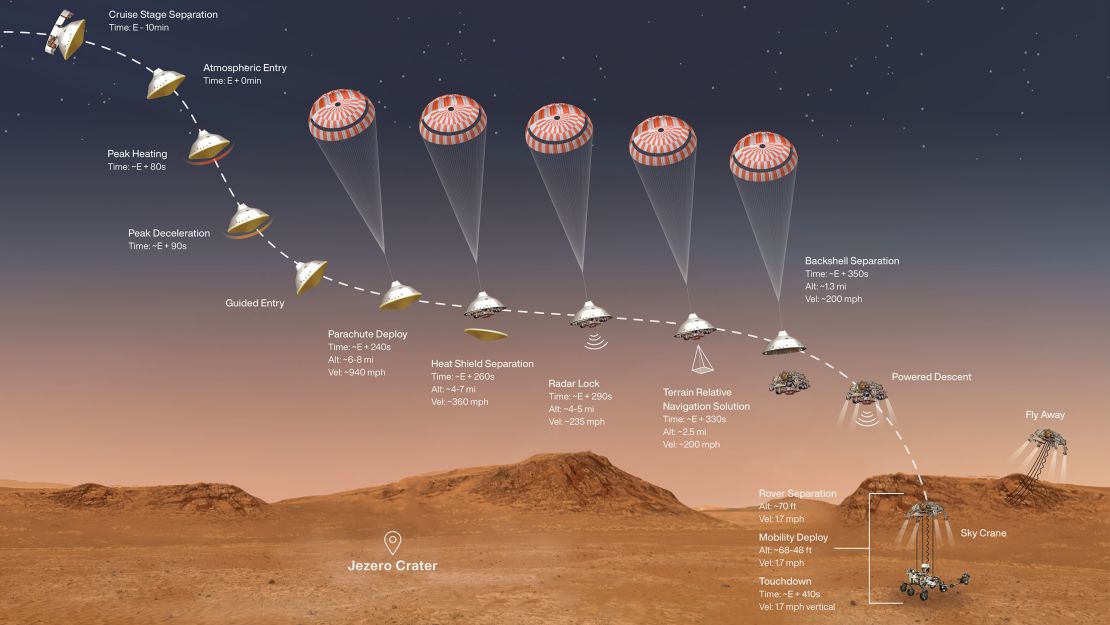

The spacecraft will streak across the Martian sky like a meteor on February 18 as it enters the atmosphere, moving at 12,000 miles per hour, said Allen Chen, Mars 2020 entry, descent and landing lead at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

About seven minutes later, the rover will slow down to softly land in Jezero Crater. This is known as the “seven minutes of terror” at NASA because a time delay between Earth and Mars means that the agency can’t interfere if something goes wrong during the landing.

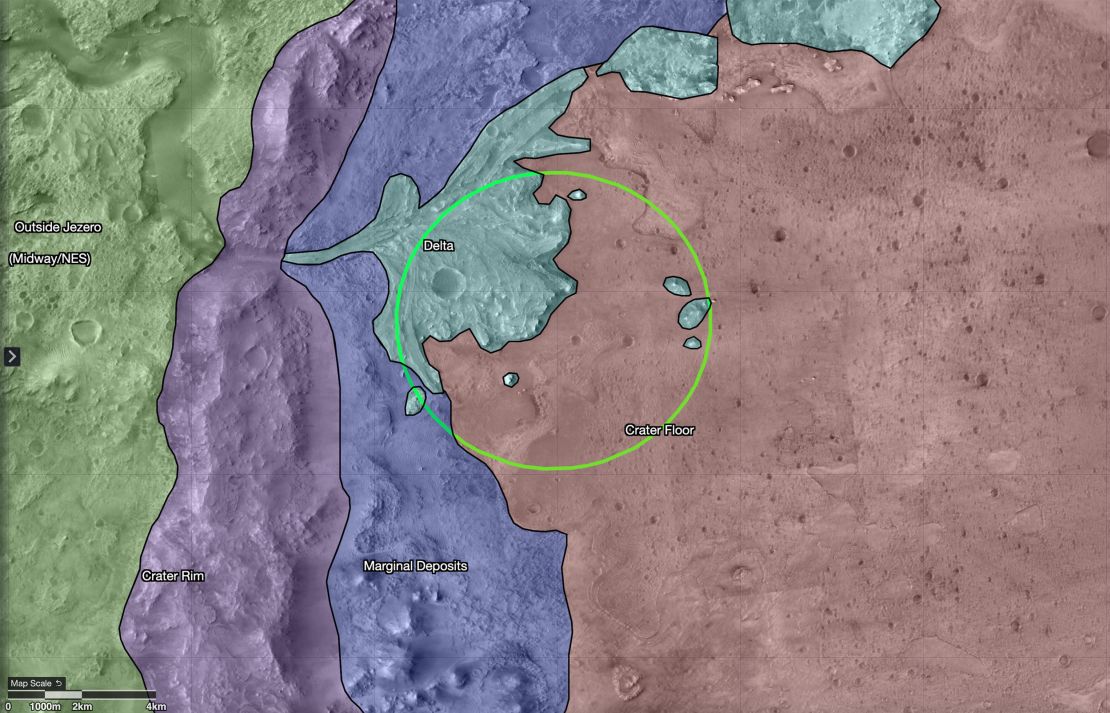

Perseverance is targeting a 28-mile-wide ancient lake bed and river delta, the most challenging site yet for a NASA spacecraft landing on Mars. Rather than being flat and smooth, the small landing site is littered with sand dunes, steep cliffs, boulders and small craters.

“Entry, descent and landing is the most critical and most dangerous part of the mission,” Chen said. “Success is never sure, and that’s especially true when we’re trying to land the biggest, heaviest and most complicated rover we’ve ever built at the most dangerous site we’ve ever attempted to land at.

“It is a magnificent place for science. But when I look at it from a landing perspective, I see danger. It’s a formidable challenge.”

Just thinking about it is enough to get Chen’s blood pumping, he said. However, when scientists selected the site, engineers worked to make sure landing there was possible.

Armed with new technology, which builds and improves upon what the Curiosity rover had when it landed, “she’s ready,” Chen said of the Perseverance rover.

And oh, the places she’ll go.

Meet Jezero Crater

Billions of years ago, Mars was a warm, wet place and likely at its most habitable – meaning that life could have existed on Mars. Over time, Mars lost its atmosphere and much of its water to become the dry, cold and inhospitable place it is today.

If we could stand on ancient Mars, as it was 3.9 billion years ago, it may have even looked a bit like Earth, with rivers and lakes cutting into its surface.

Something knocked into Mars, creating Jezero Crater, which then filled with water. It’s empty today, but scars on the surface help paint a picture of what it once looked like.

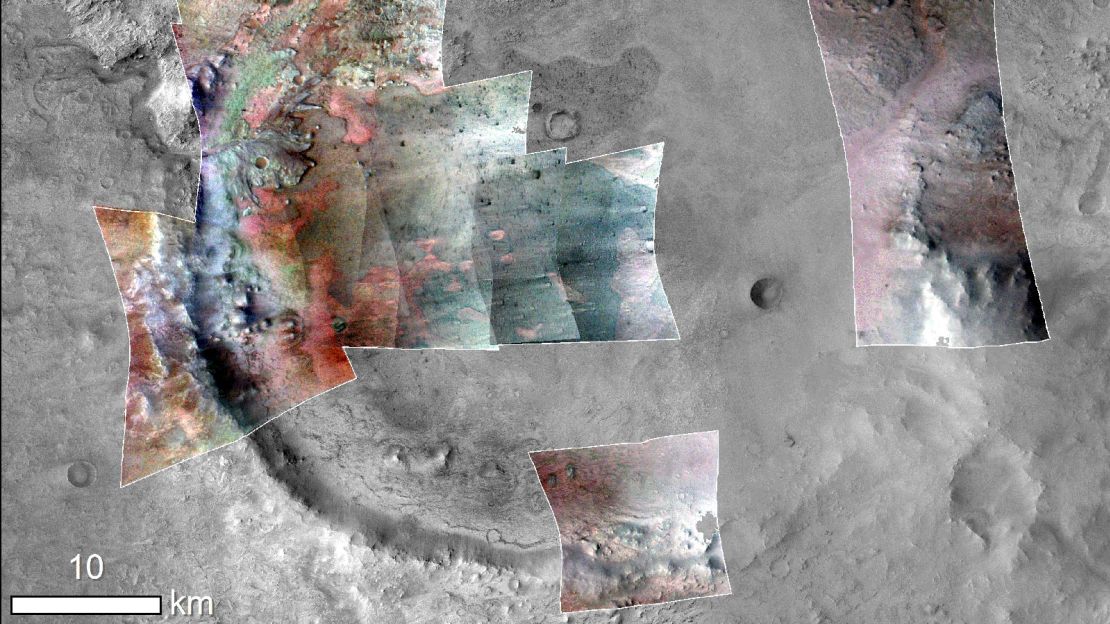

Aerial views of the site show a big river delta that looks like a fan, like where the Nile River meets the Mediterranean Sea, that flows as a channel into the ancient lake basin. That lake overflowed out the other side, creating a channel moving away from the lake in the opposite direction, said Briony Horgan, associate professor of planetary science at Purdue University and a Perseverance science team member.

Multiple aspects of Jezero appeal to scientists, said Horgan, who has led a study of the mineralogy of the site that helped lead to the selection of the crater as the landing site. Horgan is also on the team that designed one of Perseverance’s science cameras.

The delta itself is fascinatingbecause this means ancient rivers were flowing into the lake and possibly depositing organics and other potential signs of life into the lake from other areas. Deltas and lake bottoms can preserve muddy sediments that lock in evidence of ancient life or other organic material.

Boundaries between land and water are also a key place to look for evidence of past life.

While there are other ancient lake and delta sites on Mars, Jezero has special mineral deposits that make it especially attractive from a science perspective – especially for a mission that aims to collect Martian samples and return them to Earth by the 2030s.

These mineral deposits, called carbonates, are all over the crater – but they also form a feature likened to a bathtub ring around the inside of the crater and up against the rim behind the river delta, Horgan said.

Carbonates are common on Earth and form due to interactions of water and rocks. This bathtub ring is thought to correspond with ancient shorelines or beaches of the lake – places for evaporating water to create minerals.

It’s possible that the lake once had beautiful white sandy beaches, Horgan said.

In lakes on Earth, microbes like to grow in big colonies that essentially form mats just under the surface of the water. As carbonate minerals evaporatedout of the water, they could have essentially trapped those microbial mats, and biosignatures of life, in place, Horgan said.

These would act like microfossils of life on Mars.

“It’s the holy grail of Mars astrobiology exploration,” Horgan said. “This could be our only chance to do a really detailed search for ancient life on Mars, learn more about the history of Mars, and even gain insight about our solar system and Earth.

Before Mars lost most of its atmosphere to space, which scientists are still trying to understand, the planet likely had a thick atmosphere. Carbon dioxide in the air, along with water on the ground, would have formed the carbonates that the rover team is eager to investigate.

But carbonates are largely shockingly missing from the Martian surface – consider it the case of the missing carbonate. However, they dominate in Jezero Crater.

“Think about places like the Bahamas, where you have reefs teeming with life and the formation of carbonate minerals,” said Katie Morgan Stack, Perseverance deputy project scientist. “Life is using these minerals as part of biological processes.”

Jezero is a “slam dunk” because of its potential to shed light on the minerals, rocks and possible ancient life on Mars, Stack said.

A historic mission

Perseverance will land in an area it can immediately begin exploring. The rover is armed with a set of sophisticated science instruments and cameras that will not only allow it to collect samples of interest to return to Earth, but tools that can investigate the chemistry and composition of the rocks and other material Perseverance encounters.

“The rocks exposed in and around Jezero are really old and we’re tapping into a period in the solar system record that isn’t well preserved,” Stack said.

Stack is part of the three-person leadership team for the mission, which leads a team of 450 scientists around the world. Together, they will look at the images sent back by the rover to determine where and what to explore along the way.

“On the one hand, we’re seeking signs of ancient life, but we’re also thinking about diversity for the samples we’ll return to Earth,” Stack said.

Volcanic rock on Mars could provide the best absolute ages for when things happened on Mars.

After the crater has been thoroughly explored within the first two to three years, Perseverance can set off for even older ground: Isidis Basin. Jezero, which is between 3.5 and 4 billion years old, is located on the inner rim of Isidis.

Scientists suspect the massive Isidis crater was created by an even older impact 4 billion years ago, which launched some of the most ancient rocks on Mars up onto the surface. And the Perseverance team wants to explore those, too – which could open up more possibilities and even answers.

“I believe Perseverance is the best suited of any Mars mission to find potential evidence of life on Mars,” Stack said.