Christine Lloyd-Jones was at work when the first call came: One of her friends, Annette, 62, had died of coronavirus. The following day, as she ate breakfast, her phone flashed again. This time it was news of another friend, Lloyd, dead at 58. The next day, another call. Her friend Haydon, 51, was in the hospital. He died the following day. In the space of just five days, Lloyd-Jones lost three loved ones to Covid-19.

One month on, the social care manager, who lives in London, has become a one-woman publicity machine for members of the Black community, encouraging everyone she knows to get vaccinated, so she won’t have to say goodbye to another friend or family member.

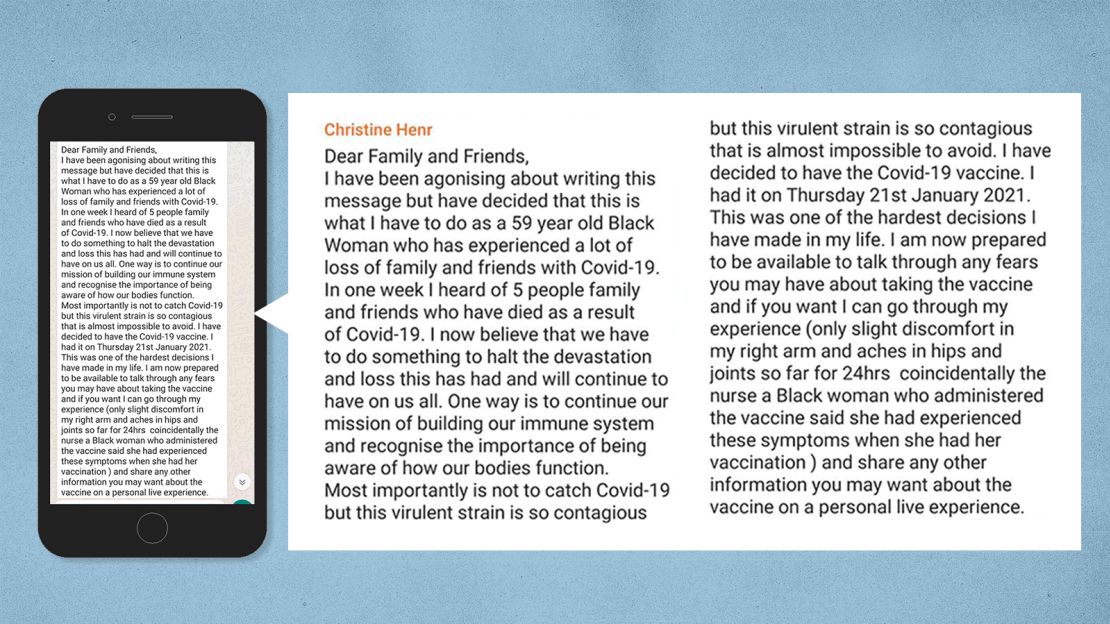

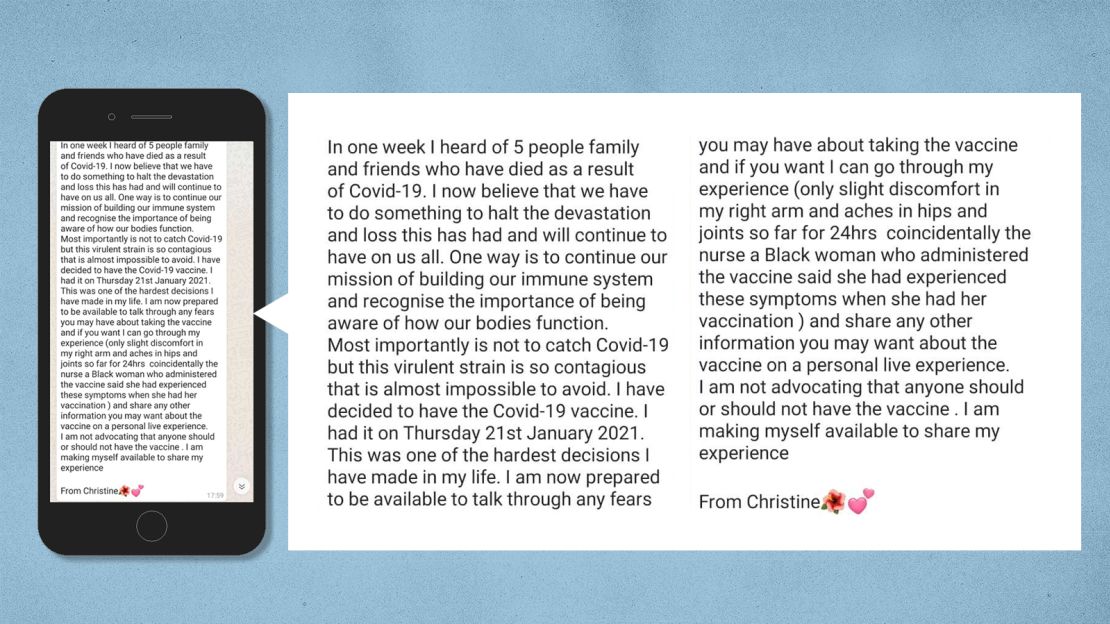

“I have been agonizing about writing this message but have decided that this is what I have to do as a 59-year-old Black woman,” read the message she sent to everyone in her WhatsApp contact book. “I now believe we must do something to halt the devastation and loss.

“I have decided to have the Covid-19 vaccine,” she wrote. “This was one of the hardest decisions I have made in my life.”

Lloyd-Jones’s uncle died from coronavirus four days after the UK locked down last March, and the twin sister of her friend Annette, called Paulette, also lost her life in 2020. The twins are buried together. Yet Lloyd-Jones is far from being the only member of Britain’s Black community or other ethnic minorities to feel unsure about taking a Covid-19 shot.

A report released by the UK Household Longitudinal Study earlier this year found that 72% of Black British respondents said they were unlikely or very unlikely to get a coronavirus vaccine.

According to the same survey, those from Britain’s Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities were also hesitant, with 42% saying they were unlikely or very unlikely to get vaccinated.

The data the report was based on was carried out in November, prior to any vaccines being approved, and those numbers are likely to have dipped in recent weeks, as the shots are rolled out with few, if any, reports of serious side effects.

But Black people and those from minority groups are still thought to be less willing to get vaccinated than their White counterparts – a factor which concerns health authorities and community leaders alike.

According to data from OpenSAFELY – an electronic platform from the UK’s National Health Service that documents coronavirus vaccine uptake – Black people over 80 were around half as likely to be vaccinated as their White counterparts, as of January 27.

Skepticism fueled by injustice

From the outset, it has been clear that people from ethnic minority backgrounds have been disproportionately impacted by Covid-19.

According to the latest report from the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS), from October, Black men in England and Wales had the highest rate of death involving Covid-19, which was 2.7 times higher than White men. Women of Black Caribbean background had a death rate that was twice that of White women in England and Wales. Additionally, the ONS found that all ethnic minority groups, other than Chinese, were dying from Covid-19 at a disproportionately higher rate than the White population.

Kamlesh Khunti, an expert in Black and minority healthcare at the UK’s University of Leicester, believes that – despite higher death rates – vaccine hesitancy in Black, Asian and other minority communities was predictable.

“We should have prepared for this, since we have seen low uptakes in flu vaccinations among minority communities,” he told CNN. “People are concerned about the contents of the vaccine because of religious and cultural concerns.”

Khunti said part of the problem was a lack of deliberate effort to reach out to people from minorities: “We don’t see the messaging coming down to the channels that most ethnic minorities listen to, especially in the languages they speak.”

Other experts say skepticism around vaccines is down to a lack of trust in medical and governmental institutions – the roots of which can be traced back to colonialism and slavery.

“People can’t disentangle where we are, in terms of medicine today, from the experimentation on colonized and indigenous people,” said Dr. Annabel Sowemimo, founder of the organization Decolonising Contraception, and author of the upcoming book “Decolonising Healthcare.”

“People think that these behaviors in minority communities are irrational or erratic, but amongst the community it is well known that these things have happened,” Sowemimo said.

For 40 years, from 1932 until 1972, the US Public Health Service conducted tests on hundreds of Black men with syphilis in Alabama. The men, many of whom were faculty and staff from Tuskegee Institute, were deliberately untreated to assess the progress of the disease.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the study became unethical in the 1940s when penicillin was recognized as the recommended drug for syphilis treatment. Penicillin was not offered to the subjects of the decades-long study.

Ever since this incident researchers must get informed consent from all persons taking part in studies.

In another case, the US-based pharmaceutical giant Pfizer paid compensation to the families of 11 children who died, and dozens more who were harmed, in Kano State, Nigeria, after some were given an experimental anti-meningitis drug, Trovan, during trials in 1996.

The suit alleged that the drug company did not obtain parental consent and did not explain that the proposed treatment was experimental. The Nigerian government said the drug caused deaths and deformities among children and had been used without approval from Nigerian regulatory agencies. Pfizer maintained that the trial was conducted with the approval of the Nigerian government and consent of the participants’ parents or guardians.

And there has been at least one suggestion to experiment on Black people during the current pandemic too.

In April 2020, two French doctors – Dr. Jean-Paul Mira, head of ICU services at the Cochin hospital in Paris, and Camille Locht, research director at France’s National Institute of Health and Medical Research – suggested during a TV debate that Covid-19 vaccines should be tested in Africa. The pair later apologized after WHO’s Director-General condemned the remarks, calling them a “hangover from a colonial mentality.”

‘Health inequalities have been ignored’

These historical and modern injustices have fueled mistrust among some in Britain’s Black and minority communities.

A lack of trust in public health providers was shown in a report by the UK’s Joint Committee on Human Rights, which found that more than 60% of Black people in the UK do not believe their health is as equally protected by the country’s National Health Service (NHS) compared to White people. Women (78%) are much more likely than men (47%) to feel that their health was not equally protected by the NHS compared to the White population, according to the research.

“Health inequalities have been ignored for a significant amount of time and that breeds resentment,” Sowemimo said. “It appears to members of minority communities that the only reason they want to address it now is because a failure to take the vaccine impacts everyone.”

The speed of the vaccination’s development has also fueled misinformation about the coronavirus vaccine.

“We need to counter misinformation with the facts as we know them in the various ways of communication at our disposal,” Dr. Tom Kenyon, chief health officer at the Project HOPE organization, told CNN. “Eventually, the facts will prevail and increased vaccination uptake will result.”

The British government has offered local councils in England more than £23 million ($31 million) to help fight misinformation around vaccines and encourage those from high-risk communities to take the shot.

But many believe that vaccine hesitancy must be fought by empowering local and community voices.

“I have people that I know who are suffering,” Lloyd-Jones told CNN. “The fact is, if we want things to move on in terms of how the vaccine is seen and received, the more people from Black and minority communities take the vaccine, the more it will spur others on to do it.”

Empowering community leaders

In more than 100 mosques across the UK, imams are delivering sermons aiming to reassure worshippers about the safety and legitimacy of Covid-19 vaccines, part of an initiative from the Mosques and Imams National Advisory Board (Minab).

In his mosque in Leeds, northern England, imam and Minab chair Qari Asim told CNN he is working to spread the message because he doesn’t want to lose another community member to the virus.

“We all have to play our part in this pandemic … I have attended so many funeral prayers and I see the trauma, pain [and] suffering that all of us have gone through. Now we see light in the darkest of moments and that light is the vaccine,” he said.

Asim believes that the messenger is just as important as the message. He told CNN that due to a lack of trust in public institutions among the Muslim community, the information needs to come from trusted local experts, such as faith leaders or doctors.

The imam says that misinformation is common and has found it is often younger generations that urge older relatives not to get a shot.

“Among young people it’s a serious concern that they don’t trust the vaccine,” Asim explained. “With the elder generations, sometimes we feel there is a language or a culture barrier and the only source of information they have is their own family members.”

The Minab initiative uses experts from varied scientific fields – from nanochip experts to fertility experts – from within the Muslim community. They address everything from common concerns, such as vaccine side-effects, to conspiracy theories around the shot.

“In this pandemic, what has really come to the fore is love, compassion and being there for each other, so as an imam I feel I need to be there for my community to help them make the right choice,” Asim said.

Better representation to encourage uptake

Vaccine hesitancy is not unique to minority communities in Britain.

A survey released on February 4 by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases found that more than half of Black adults in the United States remain hesitant to get a Covid-19 shot. The research found that only 49% of Black adults plan to get the vaccine with 19% of those people saying they will get it right away and 31% preferring to wait.

The survey, which was conducted in December 2020, showed that older Black adults and men are more willing to get the Covid-19 vaccine than respondents in other groups.

For example, 68% of adults age 60 and older said they planned to get the shot, while only 38% of Black adults age 18-44 planned to take it. Many of the younger respondents expressed distrust in the health care system saying it treats people unfairly based on race and ethnic background, according to the survey findings.

On both sides of the Atlantic, experts say that authorities must work with community leaders to help build confidence in coronavirus vaccines.

The Right Reverend Rose Hudson-Wilkin, Britain’s first Black female bishop and an ambassador for the Your Neighbour campaign, a UK Church response to the pandemic, believes better representation is one of the best ways to encourage vaccine uptake in Black, Asian and other minority communities.

“If they can begin showing Black people and Black people of note, Muslim people of note, taking the vaccine – as well as the ongoing message that we can keep one another safe – that would go a long way,” Hudson-Wilkin said.

“There also has to be some recognition that in the past things have not been right and there has been a level of distrust,” she added.

“But, as a people, if we are not showing any sense of care and responsibility for our own well-being, why should anyone else? We need to play our part, that is why it’s imperative we see people like us taking the vaccine.”

Salma Abdelaziz and Li-Lian Ahlskog Hou contributed to this report.