Donald Trump ends his tumultuous presidency with the nation confronting the greatest strain to its fundamental cohesion since the Civil War.

The January 6 assault on the US Capitol capped four years in which Trump relentlessly stoked the nation’s divisions and simultaneously provided oxygen for the growth of White nationalist extremism through his open embrace of racist language and conspiracy theories.

In the process, Trump has not only shattered the barriers between the Republican Party and far-right extremists but also enormously intensified a trend that predated him: a growing willingness inside the GOP’s mainstream to employ anti-small-d-democratic means to maintain power in a country demographically evolving away from the party.

The result has been to raise the stakes in the ideological polarization of the parties that has been reshaping American politics for decades.

Particularly since the 1990s, the parties have steadily pulled apart, with Republicans rallying the voters who are most uneasy with the way America is changing demographically, culturally and economically and Democrats mobilizing those most comfortable with the changes.

The Trump presidency, especially its chaotic final months, has shown that both the leaders and rank-and-file voters of the parties are now divided not only by their policy preferences but also by their assessments of the nation’s underlying realities, and even their commitment to the traditional norms of democracy.

In one sense, the two parties are moving away from each other in mirror image: Vast majorities of voters in each party now say in polls that they view the other side as a threat to the nation’s future.

But that assessment is provoking a more extreme reaction inside the GOP than among Democrats, as different elements of the Republican coalition have embraced a succession of anti-democratic actions culminating in the widespread support among GOP elected officials for Trump’s efforts to subvert the November election and in last week’s unprecedented assault on the Capitol by a pro-Trump mob.

All of this is unfolding against the backdrop of a pandemic that has staggered the economy, plunged millions of families into financial peril, overwhelmed America’s health care system and widened the nation’s political divisions – as Republican-leaning jurisdictions, partly because of pressure from Trump, have resisted the measures, like masking, that public health professionals consider crucial.

Coalescing at the transition point between the presidencies of Donald Trump and Joe Biden, these pressures have produced a level of internal division and cracks in the constitutional order that most experts agree exceeds even the unrest of the 1960s – and probably has only one full parallel in American history.

“It is pretty clear that this is the worst since the Civil War, and I say that without difficulty,” says Princeton University historian Sean Wilentz, the author of “The Rise of American Democracy,” a monumental history of America’s development in the 19th century. “And on top of that, what happened on the 6th was the saddest day for American democracy since April 12, 1861.”

That was the day Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, beginning the Civil War.

The great sorting out

Few experts anticipate a reprise of that experience: a formal attempt at dissolving the nation accompanied by widespread armed conflict (even if they aren’t quite as quick to dismiss the possibility as a few years ago). For one thing, today’s lines of political conflict wouldn’t allow as neat a division as the sectional North-South split over slavery in the Civil War: Our modern Mason-Dixon line separates Democratic-leaning metropolitan centers from red rural and small-town areas in every state, an impractical pattern for any actual separation.

Susan Stokes, a political scientist who directs the Chicago Center on Democracy at the University of Chicago, notes that civil wars typically also require a split in the armed forces or the emergence of a full-scale rebel army, dynamics not yet evident in America.

And Stokes, Wilentz and others point out that, for all of the pressure Trump imposed, the November 3 election and its aftermath demonstrated enormous resiliency in our political system, with voter turnout soaring to a record level despite the pandemic and courts and local election officials – including Republicans in each case – rejecting the President’s groundless claims of fraud.

“Let’s not forget we had the largest national election in American history amid the pandemic and it went off without a hitch,” says Wilentz. “November 3 was a day that will not in infamy but will live in fame for the exercise of democracy, and we ought not to forget that. There’s a lot of strength in the system.”

To most experts, all of these mitigating factors make it extremely unlikely that America will follow the path of modern countries that collapsed into full-on civil war, like Yugoslavia after communism, Spain before World War II or Latin American nations during the 1980s. But a few years ago, those comparisons would have been unthinkable, and raising them now, even to dismiss them, underscores the fractures in our political structure.

“I think we are a long way from choose your outright civil war: We’re not Yugoslavia; we’re not Spain,” says Stokes. “But we are definitely in danger of a kind of a lower-level violence, decentralized because that’s our country’s middle name, constant outbreaks, for years to come.”

These pressures emerge from the convergence of two tectonic developments in American politics, one long-gestating, the other more recent.

The longer-term process is the ideological separation of the two parties, a process that I called “the great sorting out” in my 2007 book, “The Second Civil War.” For most of American history, our political parties have been ramshackle coalitions of disparate ideological views. But starting in the 1960s, and accelerating since the 1990s, conservatives (especially Southern evangelical Whites and Northern working-class Whites) have migrated out of the Democratic Party, while moderates and liberals (especially college-educated Whites and secular voters) have migrated out of the Republican coalition.

This process has both encouraged – and been accelerated by – the development of overtly partisan media since the 1980s, which has allowed voters on each side to retreat from a shared set of understandings about the nation’s condition. The rise of social media in this century has only intensified the withdrawal from shared experience.

All of this has narrowed the differences within each party’s coalition but widened the distance between them. Both among elected officials and voters, a huge chasm now separates the parties on almost all major issues. The distance is especially foreboding on attitudes toward the big structural changes remaking American life, culturally, demographically and economically.

Republicans now dominate among the voters who polls show are most uneasy about those changes – particularly Whites who are non-urban, identify as evangelical Christians or lack college degrees.

In recent polling by the nonpartisan Public Religion Research Institute, a larger share of Republicans say Whites and Christians face significant discrimination than say the same about Blacks and Hispanics; more than three-fourths of Republicans say the values of Islam are incompatible with American values; three-fifths say American society punishes men just for acting like men; and nearly three-fifths agree with the harshly worded statement that “immigrants are invading our country and replacing our cultural and ethnic background.”

Democrats in the poll were far less likely to agree with any of those propositions. That reflects the composition of their competing coalition, which revolves around the groups generally most comfortable with the emerging America: people of color, young people, secular adults who don’t identify with any religious tradition, and college-educated White voters, particularly women.

Growing political antagonism

This demographic divide has widened the geographic separation between the parties. The GOP has been virtually exiled from the fast-growing metro areas that are driving population growth and economic dynamism: While George H.W. Bush won 57 of the nation’s 100 largest counties as recently as 1988, Trump carried just 9 of the 100 largest in November, struggling not only in heavily minority central cities but also in prosperous, well-educated inner suburbs.

Simultaneously, the GOP has solidified its control of the nation’s more uniformly White exurban, small-town and rural regions: While Bill Clinton won about half of the nation’s counties in his 1992 and 1996 presidential wins, Biden carried only about one-sixth of American counties, even while comfortably winning the popular vote.

In Congress, these hardening lines of division have made it much more difficult for presidents in either party to secure meaningful cooperation from the other; the parties now vote in lockstep against each other much more routinely than in earlier generations.

At the grassroots level, this separation has seeded rising reciprocal antagonism. In the Public Religion Research Institute polling, about four-fifths of Democrats say the Republican Party has been taken over by racists, while a virtually identical share of Republicans say the Democratic Party has been taken over by socialists. Pew polling before the election found that an even higher percentage – roughly 9-in-10 on each side – said that if the other party’s presidential candidate won in November, it would produce “lasting harm” to the nation.

This is an unusually pitched level of political antagonism, and it has unquestionably made it more difficult for Washington to make progress on big problems. But as Wilentz notes, in a country as diverse as America, “there are always tons of divisions.”

And while those divisions have contributed to dysfunction in Congress, they had not until recently raised real questions about America’s underlying political stability. Those doubts have emerged only since the long-standing polarization of the parties has been reinforced by a more recent second factor: the increasing willingness of the Republican Party to employ extreme and anti-democratic tactics to maintain power.

Trump White House

This pattern has gathered momentum for years but it’s tremendously accelerated since Trump’s emergence as the party’s leader. Signposts of this shift have come steadily over the past decade: the wave of voter identification and other laws in Republican states making it tougher to vote after the GOP’s gains in the 2010 election; the 2013 party-line Shelby County decision by Republican appointees on the Supreme Court to gut the Voting Rights Act; Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s unprecedented machinations in 2016 to prevent then-President Barack Obama from appointing a Supreme Court justice who would have tipped the majority to liberals; and the congressional Republican acquiescence to Trump’s regular threats to the rule of law, from openly extorting the government of Ukraine to manufacture dirt on Biden to attempting, for the first time in American history, to tilt the census results to the advantage of one party.

The widespread Republican support for Trump’s efforts to steal the election – which persisted to the point of a majority of House Republicans voting to overturn the results even after the mob of his supporters ransacked the Capitol – has placed a dramatic exclamation point on this retreat from democracy in the GOP, many experts agree.

“Fifty years from now when people read about [this era] they are not going to say there were two parties that were small-d democratic,” says Stokes. “They are going to say that this is a political party that was captured by autocrats, by not-democratic people.”

Desire to maintain power at all costs

To Stokes, the Republican focus on alleged fraud in the 2020 election “is sort of a big distraction” from the underlying change that’s reshaping the party. While the mass of Trump followers might accept his allegations of fraud, she notes, those claims have been disproved so thoroughly it’s hard to imagine that they are believed by many of the party leaders joining his efforts to overturn the election. And that points to a deeper, and darker, meaning for the post-election maneuvering among Republican senators, House members and state attorneys general to subvert the results.

“Pretty clearly they are not really democrats,” she says, referring to believers in democracy, not the opposing political party. “They are people who think they should win no matter what. I almost want to say to them: Why don’t you have the courage of your convictions and explain to us why the United States should not be a democracy now? Because what they are really saying is that no matter what happens, Trump needs to stay in power.”

Biden Transition

These efforts have found widespread support among Republican voters, with three-fourths or more of them routinely telling pollsters they believe the election was stolen and a majority in last week’s ABC/Washington Post survey saying GOP leaders should have done even more to try to overturn the result. Those attitudes bring to a point years of surveys showing a retreat from democratic values in a significant portion of the GOP base.

In one recent Public Religion Research Institute study, for instance, nearly three-fifths of Republicans agreed that “because things have gotten so far off track in this country, we need a leader who is willing to break some rules if that’s what it takes to set things right.” In another national survey organized by political scientist Larry Bartels, a majority of Republican voters agreed “the traditional American way of life is disappearing so fast that we may have to use force to save it.”

Many analysts believe these attitudes are inextricably linked to the anxieties about demographic and cultural change evident among GOP voters in the polling by the Public Religion Research Institute and others: At its core, the fear of demographic eclipse is eroding the commitment to democracy among both leaders and followers in the Republican Party. As Bartels, now at Vanderbilt University, noted in his paper, “The strongest predictor by far of these antidemocratic attitudes is ethnic antagonism—especially concerns about the political power and claims on government resources of immigrants, African-Americans, and Latinos.”

Republicans have lost the popular vote in seven of the past eight presidential elections, something no party had done since the formation of the modern party system in 1828. And, according to calculations by Lee Drutman, a senior fellow at New America, a centrist think tank, if you allocate half of each state’s population to each senator, GOP senators have represented a majority of the population only once in the past 40 years despite controlling the actual Senate majority about half of that time. (Today Republicans hold exactly half the Senate seats while representing only about 44% of the population, Drutman calculates.)

The determination to continue exercising majority power while attracting support from only a minority of the population, many experts agree, is the force that has pushed Republicans to retreat step by step from small d-democratic traditions – a trend raised to a visceral extreme by the literal assault on the Capitol, a core symbol of American democracy.

The widespread inroads into the GOP among the forces hostile to democratic traditions mark a key difference from the 1960s, another period of intense social discord. While America in that era also experienced enormous strain – with massive protest movements, large-scale urban unrest and riots, and anti-war radicals who regularly set off bombs at military recruiting or corporate offices – the radical elements on that continuum never achieved as much influence inside the Democratic Party as the Trump forces skeptical of democracy have established in the modern GOP.

Columbia University sociologist Todd Gitlin, who participated in the student left during the 1960s and has written one of the definitive histories of the period, notes that while “there were a lot of bombs, that’s for sure,” radicals such as the Weathermen group “were never a threat” to the nation’s core institutions because they lacked any leverage within the political system.

“Imagine if the Weathermen had had a caucus of 10 Democrats in the House who basically supported them and they in turn were allied with state Democratic parties all over the place, state legislators, etc., and so on. That would have been a political danger of a different order,” he says.

Instead, he says, the Weathermen and other militant groups such as the Black Panthers “were not politically central in the way that [today’s extremists] are. There is now a party made up substantially of people who are either friendly toward violence … or willing to look the other way. And nobody was willing to look the other way at those bombings.”

One party alone can’t fix it

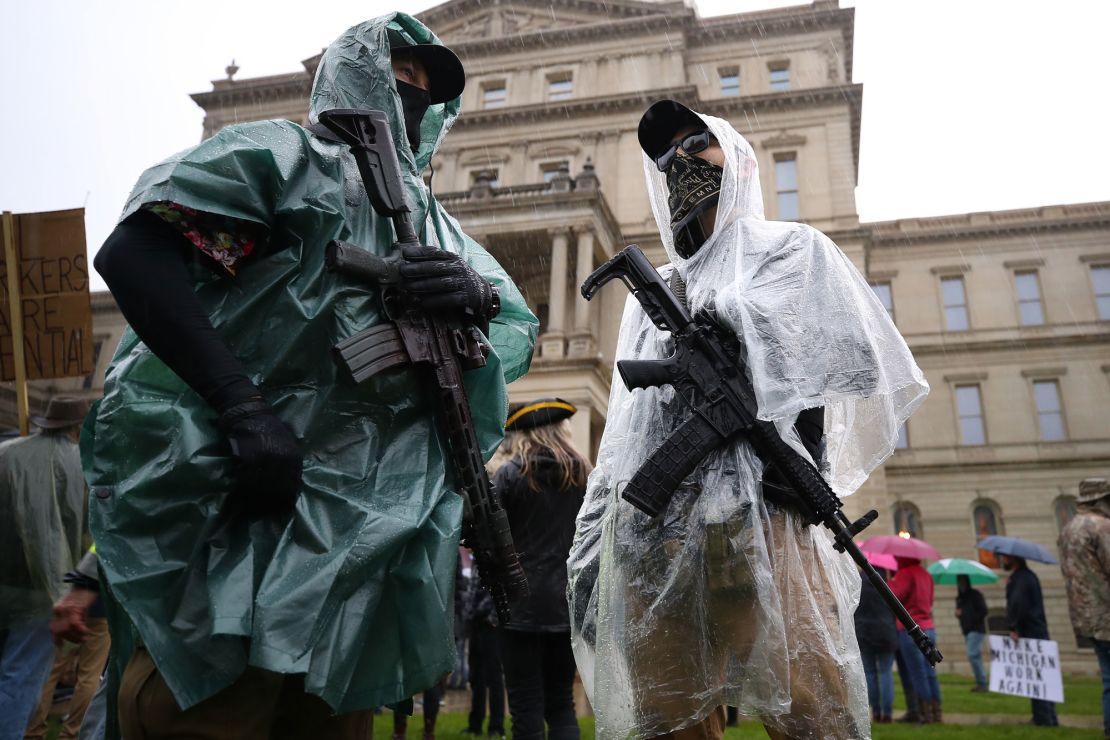

The closest American parallel to the violence unleased by Trump supporters at the Capitol – and earlier threats like the armed protests against Covid restrictions and the subsequent plot to kidnap Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer in Michigan – may be the pro-slavery Democratic Party around the Civil War. Especially after the conflict, White racists across the South employed a massive campaign of violence to undermine the biracial Reconstruction governments and prevent the former slaves from exercising their new freedoms, including the right to vote.

That bitter and bloody tradition lingered through nearly a full century of lynchings and other violence to deny the vote and civil rights to Blacks across the Jim Crow South – all with the support of the Dixiecrat Southern Democrats.

Seen against that history, the upsurge in White nationalist violence under Trump seems less like a new phenomenon than the resurgence of an old one – a determination to use force to maintain a clear racial hierarchy. Political scientist Alvin Tillery, director of the Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy at Northwestern University, says Trump’s success at mobilizing an electoral coalition resistant to demographic change underscores the country’s imperfect progress toward creating a true multiracial democracy. While America has formally been a democracy since its birth in the 1700s, he notes, for most of our history those democratic rights were limited solely to White men.

Democracy, he says, is much easier to sustain when it’s limited to “a master race … where your skin color or your gender determined your rights and your status.” Only since the 1960s, with the passage of the Voting Rights Act and immigration revisions that led to a rapid growth in the nation’s racial diversity, did “we really start trying, with much great difficulty, to be a multiracial, gender-equitable LGBTQ-plus tolerant democracy. That’s why we have these struggles.”

Few are willing to hazard definitive predictions about whether America will pull back from this brink and restore more stability to the political system – or spiral further into conflict and division. Biden, who will assume the presidency Wednesday, appears to be betting primarily on a strategy of narrowing divisions by providing bread-and-butter improvements in people’s daily lives: more vaccine shots in their arms, more Covid relief money in their pockets – while stepping up law enforcement efforts against White nationalist groups.

That approach might help contain the problem, but most experts agree it is unlikely to end it. While the inclination among Democrats may be “let’s just get to the bread-and-butter issue,” says Tillery, “that’s not necessarily the motivation of the people that sacked the Capitol.”

In the long run, whatever Biden and other Democrats do, the question of whether the US faces more violence and other threats to its fundamental political stability probably rests more with the choices that Republicans make. If the party continues to validate and welcome extremists at its fringe and move further toward adopting anti-democratic tactics in its mainstream, the nation could be locked into a cycle of rising disorder – particularly because the growing racial and religious diversity that triggers so much of the alienation in the Republican coalition will only intensify in the years ahead.

Wilentz notes there has always been a minority of Americans who embrace conspiracy theories, tolerate violence to advance their goals and are willing to ditch democracy to maintain power for their side. But for much of American history, their influence has been controlled because neither party would fully embrace their causes; that’s the barrier that has cracked in the GOP, especially during the tempestuous Trump years.

“That 35% has always been there, let alone the really crackpot 15%,” Wilentz says. “The point is they were contained because both parties respected each other and respected what political representative democracy was all about. The Republican Party forgot to do that. The Republican Party stopped doing that. And that is what unleashed this force.”

However hard Biden tries, history suggests that one party alone is unlikely to repair the widening domestic divisions that may stand as Trump’s clearest legacy. It’s likely that both parties will need to commit to undoing Trump’s damage to America’s political stability – or that damage won’t be undone at all.