On holiday in Iceland a few years ago, Pranav Lal listened to the Northern Lights. As they danced above his head he heard noises, swift and high-pitched, he recalls. Out of these sounds, shapes and patterns emerged, and from them, images.

Lal, a consultant from New Delhi, was born blind, yet he can “see” thanks to technology called “The vOICe,” which turns live camera images into sounds. As the camera scans from left to right, the pitch of the sounds denotes the elevation of objects, while the volume defines brightness. By learning to interpret the subtleties of the noises, it’s possible to have a form of functional sight.

Pioneered by Dutch engineer Peter Meijer in the 1980s, The vOICe has evolved significantly. Through Meijer’s website Seeing with Sound, it is available via glasses mounted with a camera, but also free to use for Android mobile devices, Raspberry Pi computers and as a web app; Lal even uses the software on his laptop screen, allowing him to shop online and view images of outer space.

“The major challenge is to learn to interpret those image sounds,” Meijer tells CNN.

This is why Lal turned to photography in the early 2000s. “I joined the Seeing with Sound mailing list and I slowly started asking questions: ‘I heard a sound like this, what could it mean?’” he explains. “I needed to share with the world what I was looking at so that they could answer my questions.”

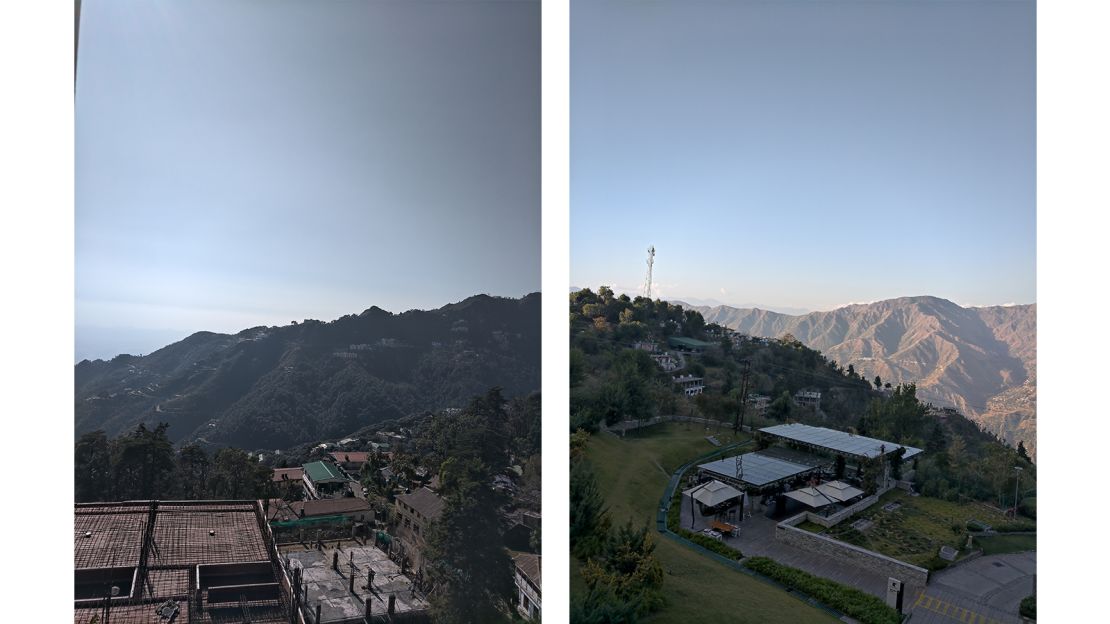

What started as a way to interpret objects became a hobby, with his main focus landscapes and architecture. With the sounds as his guide, Lal uses his smart glasses to position his camera.

“For me, more than photography, it is the journey of exploration and looking at an environment,” he says. “When I travel, I actually now can be a ‘real tourist’ – I gawk in the interest of science.”

Lal’s photography has been widely shared and he’s formed bonds with sighted photographers on his travels. His conversations have highlighted both the similarities in their pursuit, and also the differences.

“Most of my work is with light, shadow and shape,” he explains. “What I have discovered … is (sighted photographers) also do some work with color.”

Moreover, he’s surprised that, even for sighted people, description of photography is common. “If you go to an exhibition, every image is captioned,” Lal says. “It appears that even to the sighted public, the context of the photograph is a foundation for appreciating (it), to some extent.”

His travels have been curtailed by the pandemic, but when the world opens up again he’d like to experience the mountains of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, watch the Northern Lights again and walk on the seafloor in vOICe-enabled glasses to “see what things look like under the ocean.”

Lal praises Meijer’s free and “flexible” software and continues to experiment with adapting it with emerging hardware to augment his sight even further. The vOICe in combination with the iPhone 12 Pro’s LIDAR functionality could add depth mapping to his vision, for example.

“I think there is a lot of enhancement possible,” he says. “I think we can go beyond organic vision, perhaps, or at least use other kinds of sensors to substitute for organic vision.”

But for all the profound leaps in technology, sometimes their most important functions lie in the everyday.

In November, Lal was in an Indian holiday resort and in need of the bathroom. “I walk into the men’s (and) there isn’t a soul in sight,” he recalls. “If you’re blind you use a cane; you would tap your way around. But I wanted non-contact.

“I see this cluster of lights, a dim thing in front. It turns out to be a washbasin … I kept walking and saw these tall walls at different intervals. Separations. (It) could be a urinal, so I turned and centered myself and moved ahead, reaching it without touching anything.”

“Without the vOICe I would have had to feel everything … and who knows what’s there,” he says. “It gives me a fair bit of autonomy and a lot of information.”