Editor’s Note: Jeremi Suri holds the Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is a professor of history and public affairs. He is the author and editor of nine books, most recently “The Impossible Presidency: The Rise and Fall of America’s Highest Office.” The views expressed here are his. Read more opinion on CNN.

Americans’ assumptions about elections in the United States do not match the current or historical reality. With few exceptions, American elections have been messy, time-consuming, contested and sometimes violent. The frustrating uncertainty about the 2020 contest between Joe Biden and President Donald Trump is startling only because we do not know our own history, and refuse to recognize the inherited weaknesses in our democratic system which we must, at last, reform.

American national elections are probably the most decentralized in the world. Each state sets its own rules, and thousands of counties collect and tabulate the ballots. Two neighborhoods divided by a county line are likely to offer different voting hours, voting machines and counting methods. Two states sharing a border are likely to have vastly different rules for how citizens register to vote, and whether they can vote early, by mail or in a drive-thru facility.

The decentralized nature of American elections provides some security against efforts at national or foreign sabotage, but it also causes confusion for citizens. Watching election returns Tuesday night, I could see it was very difficult for viewers to understand which ballots (early, mail, in-person?) were being counted, and what they represented for overall electoral results. The variation in vote counting procedures in Pennsylvania and Florida, two key swing states, for instance, made it difficult to interpret who was really winning.

Complexity and decentralization, while they help prevent a widespread co-opting or disruption of our elections by bad actors, also allow local officials to manipulate voting rules, disenfranchising millions of voters. County voting commissioners and secretaries of state have consistently used barriers – including poll taxes, literacy tests and onerous registration requirements – to deny citizens their right to vote.

This was particularly true in Southern states from the late 19th century until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In recent decades, state and country leaders have distorted voter turnout in less obvious ways, limiting voting locations for certain populations while offering extensive voting opportunities for favored groups. These practices continue today.

Intimidation, cheating and threats of violence have also been common elements of American elections. As recently as the mid-20th century, candidates and their allies helped supporters to vote multiple times, some even after they died.

The most famous example is Lyndon Johnson’s election to the US Senate in 1948, when turnout of the deceased surged in the last hours to give the young Texan the last few votes he need, in alphabetical order. Decades earlier, urban political machines like Tammany Hall in New York frequently gathered poor workers from factories, filled them with drink, and transported them to voting locations with a prepared ballot. Partisanship was about much more than politics; it was a required part of employment for a number of citizens.

Stricter federal law enforcement has largely eliminated these forms of fraud from American elections. The federal Consent Decree of 1982, for instance, prohibited employers or activists from loitering near polls, and conducting similar activities, to intimidate voters. But other kinds of bias and bullying have become common, especially after a federal court refused the extend the Consent Decree in November 2016, following a complaint against Donald Trump’s first presidential campaign.

The real election corruption today centers on suppressing votes and limiting the ability to count them. In many states, including Texas, citizens concerned about Covid-19 had to choose between risking exposure or not voting. Thousands who voted legally by mail have had their ballots disqualified because the post office slowed their delivery.

Social media has become a ubiquitous and invasive channel for intimidating, shaming and spreading misinformation. The rise of the conspiratorial political social media site, QAnon, is an example of how information can be weaponized to manipulate voters and amplified by the President. At least one QAnon follower, Marjorie Taylor Greene, has now been elected to House of Representatives from Georgia. She is not the first conspiracy promoter elected to Congress, but one of the most outrageous recent examples.

President Trump, who refused to renounce QAnon, is the most prominent bully and spreader of misinformation that confuses voters. His false claim that states should not count all the legal votes against him – unprecedented in American history – is the most recent example of his bullying and intimidation. His campaign has filed suit to stop the counting of ballots in Michigan, even after the state completed its count.

What we hear, see and feel today is a manifestation of this long, troubling history of American elections. This year we witnessed an exciting surge in voter turnout, but the total number of voters strangely matters less than where they voted.

The thousands of new voters in California, for example, have no effect on the electoral vote totals for president. Rural counties in sparsely populated states, like Montana and Wyoming, have a disproportionate influence on the choice of president. Washington, DC is underrepresented with only three electoral votes and Puerto Rico is excluded completely from the election of national leaders.

Saturated with television and social media, our elections have become a drama frustratingly divorced from democracy. We are not watching the enactment of the popular will, but instead a game where the rules are intricately complex and manipulated by particular actors. We have become avid spectators, rather than active citizens choosing those who best represents us.

We are confused by what we see, horrified by how it plays out, and deeply dissatisfied with the process, even when our candidate wins. In the current media environment, our elections breed cynicism and division, degrading our democracy each cycle.

What should we do? Lashing out against one politician or party only makes things worse. We must remember that our elections have a long, difficult history. We can use that history to draw attention to inherited problems and motivate a search for alternatives. We must recognize that we are a very flawed democracy in how we choose our leaders. Other democracies offer possibilities for reform that we might consider.

We need to start a conversation about electoral reform as a society. It will not be easy, but it offers a therapeutic possibility. The current frustration is only made worse with every election. Working to change the system, beginning locally perhaps, we can at least feel like we are doing something useful.

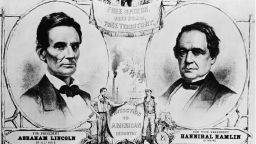

I am so tired of counting electoral votes on a map. I want to be part of a system that elects the best among us to lead, and, to cite Abraham Lincoln, inspires “the better angels of our nature.”