When Rosa Inchausti and her colleagues started testing wastewater in Tempe, Arizona, it was 2018 and they were not looking for coronavirus. They were tracking the opioid epidemic.

But because they were set up to sample the city sector by sector, they were able to switch gears and begin sampling sewage for evidence of coronavirus.

“We were ready for this,” Inchausti told CNN.

Now the city is regularly sampling sewers to keep an eye on the pandemic. And things are not looking good in parts of Tempe.

And they’re not looking good in Boston, or in Reno, Nevada, or in many other cities across the country.

As daily coronavirus counts top 70,000 as measured by standard testing, sewage testing suggests things are going to get a whole lot worse.

“It’s a leading indicator,” Inchausti said. “The proof is in the poop.”

Across the country, cities and universities are testing sewage to monitor the virus. Studies suggest it’s a useful way to augment standard person-by-person coronavirus testing and while a sewage sample cannot point to an infected individual, it can give an indication that infections are circulating in an area, a neighborhood or even in an individual building.

Early on in the pandemic, it became clear that Covid-19 virus makes its way into the digestive system and could be found in human feces. From there, it’s just a quick flush into the sewers.

Mariana Matus, co-founder and CEO of Biobot Analytics, which is analyzing sewage for dozens of customers, said sewage testing can show virus is starting to circulate even before people start showing up at hospitals and clinics and before they start lining up for Covid-19 tests.

“People start shedding virus pretty quickly after they are infected and before they start showing symptoms,” Matus told CNN.

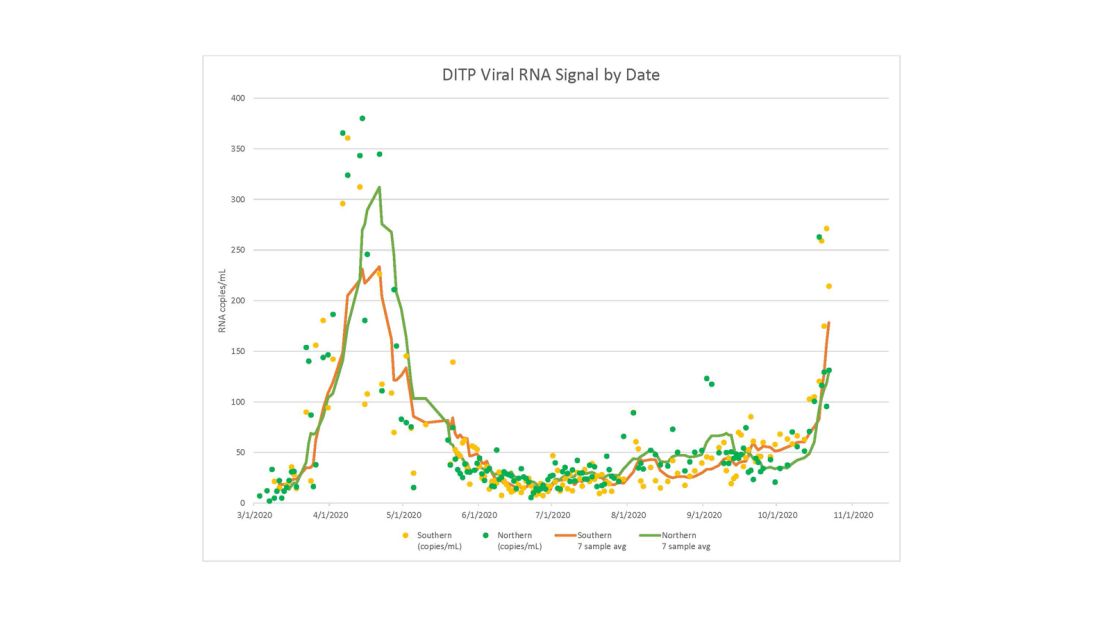

The results are clear on the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority website, which displays Biobot’s analysis of data covering 2 million MWRA customers in the Boston area. It shows a spike in viral samples in April and May, falling back through the summer. Now the virus is showing up again, with samples at levels close to what was seen at the height on the pandemic in the spring.

“We are seeing an upturn in the wastewater data which I think broadly matches what we are seeing across the country,” Matus said. “It’s been interesting seeing this almost second wave.”

Massachusetts still has a low percentage of coronavirus tests coming back positive at 1.5%. But the growing number of positive hits from the sewage indicate more positive tests are to come, Matus said.

“I think that it is pretty good evidence that we need to pay attention. Communities need to pay attention,” said Matus, a biologist who started the company with a small group of colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The little startup has been deluged with requests to test wastewater systems, she said. “Who doesn’t like a poop story?” Matus asked.

Testing the sewage for evidence of Covid-19 is like preparing a weather forecast, said Krishna Pagilla, chair of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Nevada, Reno and director of the Nevada Water Innovation Institute.

“This is something that we should have concentrated on from the beginning in every community,” Reno’s Pagilla told CNN.

The coronavirus breaks down fairly quickly once it’s flushed. Wastewater testing doesn’t recover whole virus, but instead pulls out two specific pieces of viral material called RNA. It can no longer infect people, but is easy to identify.

Finding this RNA in the sewage tells researchers someone infected is using the system. The more RNA is there, the more people are infected.

“We will know a few days in advance. We can inform the health authorities,” Pagilla said.

It’s especially useful in a college town, Pagilla said

“People are reluctant to get tested now,” he said. “Or we have students who say ‘hey I am having symptoms but I am going to hang out at home.’ They don’t get seriously ill, so they don’t get tested. But then maybe they decide to go to the gym.”

In Tempe, Inchausti said the city makes even more direct use of the information.

“The relationship is never just to have the data and look at it and say, ‘that’s nice,’ she said.

Instead, Inchausti, who is the city’s Strategic Management & Diversity director, said her team publishes the data on a public website and has used it to target low-income neighborhoods heavily populated by minorities who are most at risk of dying from Covid-19.

One, designated Area 6, abuts the Arizona State University campus. Its 8,100 residents are largely low-income. When coronavirus RNA counts went up in the sewage there recently, Inchausti said, “we spent $15,000 blitzing it with masks.”

“We met people where they are,” she added. “We understood they were going to the laundromat, so we helped them understand how to stay safe in the laundromat. We provided Covid-19 saliva testing in the school, in the neighborhood.” Now they’re analyzing test data to see if the intervention made a difference.

“I believe what Tempe is doing is the right way to do it,” Pagilla said.

Cresten Mansfeldt says he thinks it made a difference on the campus at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

The school has coordinated saliva tests for on-campus residents with regular wastewater monitoring conducted by students.

“They look at the data daily,” said Mansfeldt, an assistant professor of environmental engineering, who normally studies how microbes interact with the chemicals people excrete in their waste.

“There is a lot of information that people flush down the toilet,” Mansfeldt said.

Numbers shot up in the weeks after students returned to campus in late August, peaking at 130 positive PCR tests on September 17. But they plummeted to just a few a day after the city and county of Boulder instituted restrictions on college-aged residents that prevented gatherings of any size – not even two people – for two weeks. Officials relented after a week when students complained of safety issues, allowing those age 18 to 22 to travel in pairs.

Currently, 18- to 22-year-olds are no longer restricted any more than any other age group in Boulder county.

Now campus cases are ticking up again, from one case on October 16 to five on October 22 and eight on October 26. But Mansfeldt said the wastewater indicators look good. “Most sewers are testing negative,” he said.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Inchausti and Pagilla both said they hoped state and federal officials would pay attention and start using sewage data to monitor the pandemic across the country as a whole – and to respond.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has set up a website and is hoping state, tribal, local and territorial health departments will submit wastewater testing data for a national database.

“At this time, point estimates of community infection based on wastewater measurements should not be used,” the CDC advises.