Conspiracy theories have always been a part of the American story. But while believers used to dwell at the fringes of polite society, proponents of some outlandish and deeply harmful theories have increasingly entered the mainstream.

Now, QAnon supporters, Sandy Hook truthers, birthers, Pizzagaters, anti-vaxxers and science denialists move openly in influential circles. They occupy powerful positions, legislative chambers and government agencies. Emboldened, fellow believers emerge from stigma’s long shadow to push their conspiracies further into the light.

In our current climate, truth is so elusive that even when the President himself says he has Covid, some people still doubt it.

We have entered a golden age for conspiracy theories – a crease in a candidate’s shirt can even spark one – and there’s a reason it’s all happening right now.

How did we get here? Looking back, the path was clear all along.

It starts with a crisis

Pick one. Let’s start with coronavirus. Understanding something as complex as a pandemic doesn’t play to humanity’s strong suits. We’re notoriously bad with risk and scale. Without deep knowledge of statistics or immunology, it’s hard to grasp the full impact of it all. Then there’s the paranoia, the economic fallout, and the crushing mental weight of isolation.

Add in some widespread unrest, and with it, shifting racial paradigms that chip away at closely held identities and narratives. Is that not enough? Don’t forget the full rancor of a divisive presidential election, one framed as a battle for the very soul of our nation.

In this environment, nothing seems clear. But at the same time, everything feels painfully, critically important.

“When there are huge events that challenge someone’s core identity, especially the American identity, there is a spreading of this type of thinking,” says Molly McKew, an expert on Russian influence and information warfare and a senior adviser for the Stand up Republic Foundation.

“Everybody feels that things aren’t going right for them and that the system is failing them. There is a quiet unraveling of everything that we trust.”

Doubt grows

When the world is off its axis, concepts of truth and trust start to get dislodged. In the US, our commonly held notions of truth have been eroded by years of alternative facts and constant calls of “fake news.” Media outlets are branded as liars, and even long-respected scientific institutions like the CDC are shrouded with doubt at a time when their expertise is needed most.

“That kind of distrust is built up over time through the erosion of shared beliefs, of validity and objectivity, and of certain things in society that we all kind of agreed to,” says John Grohol, a psychologist and founder of the Society for Participatory Medicine.

Under the stress of crisis, these fractures of doubt can become chasms of mistrust.

For instance, McKew has worked in former Soviet states and observed how the Russian government has propagated disinformation campaigns at times of crisis to further certain agendas.

“A conspiracy theory tells you how things are supposed to make sense and where you fit in. This is normally a function provided by religion, or your sense of community, your society or your government,” she says.

“But we’re in this weird disruption era where all of those things feel very fragile and there is some open space to ask what the answers are.”

An easier explanation arises

Facing these world-altering problems, people search for the order in the chaos. Unfortunately, it’s not always that easy.

“We live in a super complex society that’s only getting more complex. And that means difficulty navigating those complexities,” says Grohol.

“With a conspiracy theory, a person can turn off that complexity. Wouldn’t it be simple instead, they think, to believe that there is, say, one group of people that has an enormous amount of power? In their mind, that brings more order to the world and simplifies it.”

Though some conspiracy theories seem outlandishly convoluted, the worldview they point back to is actually quite simple. It’s one of order.

Grohol mentions 9/11 and the various theories – all thoroughly debunked – that center around when and how the World Trade Center buildings fell.

“The complex, real explanation had to do with structural engineering and how the buildings were made and reacted to catastrophic destruction, but on a basic level it’s hard to understand because it’s such a tragic incident,” he said. “If we explain it with this other kind of logic, that makes it seem a little less tragic.”

In a world where everything is ruled by an unseen hand and everything happens for a reason, terrorists don’t fly planes into buildings. Men don’t slaughter schoolchildren in their classrooms or worshipers in churches.

In this simple world, politicians are either very good or very bad and the notion that tiny molecules made of the same stuff in your aluminum foil are put into a syringe to ward off disease sounds like fantasy.

From this perspective, elaborate notions of “false flags” and secret-society power grabs make a little more sense – in theory, at least.

The believers are connected

The internet, as usual, acts as a potent alchemical vessel for these ideas. Not only does it allow believers to connect with each other, but sophisticated algorithms and the self-limiting power of social media lets people seal themselves off from dissenting views.

These online factions also serve an important psychological purpose.

“People who believe conspiracies are generally more socially alienated and feel disconnected from society in general,” says Grohol. “These are people who are already primed and may feel lonely and disaffected, and the internet gives them a place to come together and share their false beliefs.”

That can create a powerful sense of community, of “us against the word,” embodied in slogans like QAnon’s “Where We Go One We Go All.”

“People desire that social connectedness, and if they were to reverse their conspiracy thinking, they would have to give up that social connectedness,” Grohol says.

Their beliefs are reinforced

Once firmly inside their echo chamber, whether it’s an online forum or a carefully curated Twitter feed, the conspiracy theory can run rampant, often taking over followers’ lives.

McKew says QAnon propagators are especially good at this.

“QAnon people have been hyper-interpreting any potential signal from President Trump that he supports them,” she says. ” From very early on, they were finding things that they think point to the fact that he’s in on it … You have to participate in it to be a believer, you have to figure out the cues and do the research.”

President Trump and members of his administration have openly courted QAnon sympathizers and have even endorsed a known QAnon supporter for a House seat in Georgia. Their embrace of such believers, along with climate change deniers and other conspiracy theorists, is a gift to a group of people whose ideas are typically rejected by mainstream society.

And once those beliefs are reinforced, they become virtually immovable.

“If you try to use facts and evidence to argue, people who are interested in conspiracy theories may reject that reasoning because it’s not a belief that’s based in fact. It’s based in a belief system, and it’s very difficult to argue with that,” Grohol says.

Furthermore, challenging a conspiracy theory often has the unwanted result of reinforcing the theory to its believers.

“If you were to flag a false video online, or create a campaign to identify mistruths, that just becomes another example for a lot of conspiracy theorists that the system is working against them, and that they’re trying to censor the truth,” Grohol says.

The theories adapt

Even when a conspiracy theory or disinformation campaign is disproved, it’s not easy for followers to just let go of their beliefs.

“If you’re recruiting for a conspiracy, confirmation bias is a huge factor in the hardening and expansion of it,” McKew says. “As long as the air of it feels true, it allows people to believe in parts of the theory and not the whole.”

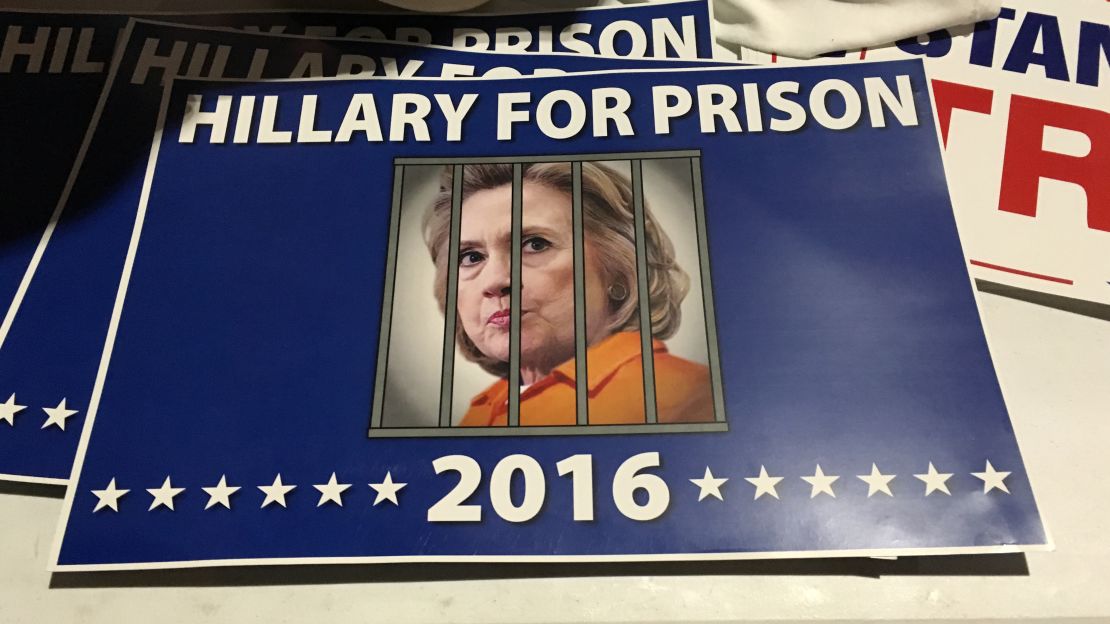

QAnon is a perfect example of these moving goal posts. Every failed prediction – that Special Counsel Robert Mueller was working with Trump, that Hillary Clinton would be arrested – was framed by the theory’s creators as just another twist in a never-ending game.

It’s not unlike religious cults who would predict the date of the end of the world.

“Once they’d get the date wrong, they’d just do new calculations,” McKew says. “Things may go wrong, but as long as the core tenets of a theory still hold, the vague bare bones of it, people will explain it away.”

The damage is done

These theories may start as the harmless whispers of a silent online minority, but once they get traction, they can create serious damage.

Sandy Hook truthers, who believe the murder of 20 children and 6 adults at a school in Connecticut in 2012 was a false flag operation to justify stricter gun laws, have terrorized the families of the victims for years. Right-wing media personality Alex Jones, a prominent Sandy Hook truther and vocal supporter of President Trump, was taken to court over his role in the conspiracy theory (which he now rejects).

Anti-vaxxers and climate change deniers threaten to halt scientific progress and have ushered in new threats of disease and pollution.

Believers of Pizzagate, QAnon and other political conspiracy theories have staged dangerous confrontations and taken resources away from real crisis situations.

The list goes on.

“It’s dangerous and terrifying,” McKew says. “The demonization and the dehumanization preached by these conspiracies allows followers to do and say terrible things in the name of their beliefs.”

When these theories are weaponized, the delicate balance of our world, already disrupted by crisis, threatens to upend completely. Truth becomes meaningless, trust is foolishness, paranoia is strength, perception is a lie.

And when nothing seems to be true, anything can be.