UK school students will now receive the grades their teachers predicted for them in their critically-important A-level and GCSE exams, after regulators announced a dramatic U-turn following a national controversy and protests over exam results.

English, Welsh and Northern Irish regulators said Monday that A-levels, which determine university entrance and are usually taken by 18-year-olds, would no longer be determined by a controversial algorithm.

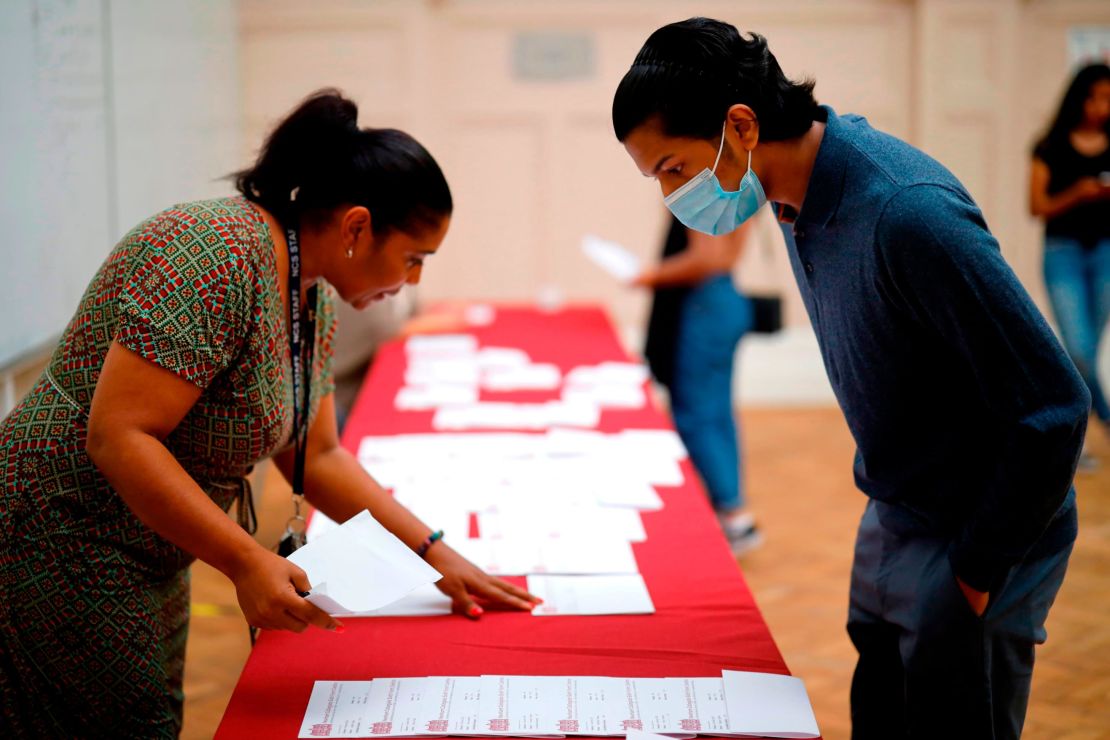

After the exams were canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic, students were instead graded based on an algorithm – the results of which were announced last Thursday.

This saw close to 40% of students’ A-level grades in England downgraded from those predicted by their teachers, according to the Office for Qualifications and Exam Regulation (Ofqual).

More than 200,000 results were downgraded, changing the futures of tens of thousands of students who needed set grades to get into university.

Many students lost out on places at their chosen universities because they were not given the grades they were predicted. Campaigners say that the downgrading disproportionately affected students from more disadvantaged and diverse schools.

The widespread downgrading left young people heartbroken and sparked mass protests, with students seen burning their results in London’s Parliament Square.

In an interview after the U-turn was announced on Monday afternoon, Education Secretary Gavin Williamson said he was “incredibly sorry for all those students who have been through this.”

Williamson said the government had tried to “ensure that we have the fairest possible system,” but that there were “unfairnesses” in the way the grades were allocated.

“Over the weekend it became clearer to me that there were a … number of students who were getting grades that frankly they shouldn’t have been getting,” he said, adding that it was “apparent that action needed to be taken.”

“We understand this has been a distressing time for students, who were awarded exam results last week for exams they never took,” said Roger Taylor, Chair of the Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual), in a statement.

“The pandemic has created circumstances no one could have ever imagined or wished for,” Taylor said. “We want to now take steps to remove as much stress and uncertainty for young people as possible – and to free up heads and teachers to work towards the important task of getting all schools open in two weeks.”

“After reflection, we have decided that the best way to do this is to award grades on the basis of what teachers submitted,” he added.

Center assessment grades (those predicted by students’ schools) will now be used for final-year A-level students, and for GCSE results that younger (usually 16-year-old) students will receive later this week.

Taylor said that Ofqual had been asked by the government to develop a system for awarding grades that maintained standards, but recognized “that it has also caused real anguish and damaged public confidence.”

Thomas Chandler, from Richmond in North Yorkshire, was predicted three A*s by his teachers. He needed an A* in English or German to get into Cambridge University to study Classics, but both were downgraded to As and he was rejected.

“It’s incredibly frustrating and upsetting,” he told CNN. “It could quite negatively impact my mental health. Financially, obviously it’s also very hard.”

He said the way the UK government had handled the situation had been “atrocious.”

A document released by Ofqual showed that 40% of students received results one or two grades lower than their advance grades, according to the non-profit Good Law Project; 3.5% of A-level results – more than 30,000 – were reduced by two or more grades.

U-turn too late for some?

Ofqual initially said that students would be able to appeal their results for free, before saying on Sunday that the new criteria would need to be reviewed. This was followed by the about-turn on Monday.

But for many students, it may already be too late.

Gemma Abbott, the Good Law Project’s legal director, told CNN: “On the face of it, reverting to center assessment grades is the fairest way to deal with the situation we are now in. It’s not perfect, but it is significantly better than the Ofqual algorithm.

“There are ramifications to the government’s incompetence and prevarications that cannot be undone, however: In particular, it seems likely that some university places will have to be deferred until next year due to issues of space. And I don’t think the young people affected by this will easily forgive – or forget – the government’s willingness to sacrifice their hopes and dreams in pursuit of the much less important goal of minimizing grade inflation.”

“This is a cohort of young people who have had unprecedented disruption to their education. So they’ve already been in a really difficult situation,” she added.

The Good Law Project, which launched legal action against Ofqual on behalf of six students, said the reductions affected students from disadvantaged and diverse schools to a much greater extent. Some institutions saw 80% of their students downgraded.

Conversely, fee-paying schools saw an overall increase in the number of their students achieving the top grades – by some 4.7% from 2019.

The Good Law Project said this appeared to be due to the fact that students in larger classes were allocated grades almost exclusively based on patterns of attainment at their institution in previous years.

Keir Starmer, leader of the opposition Labour Party, tweeted on Monday: “The Government has had months to sort out exams and has now been forced into a screeching U-turn after days of confusion.

“This is a victory for the thousands of young people who have powerfully made their voices heard this past week.”

Schools across Europe have faced similar challenges. France canceled its final baccalaureate exams and said grades would be awarded on the basis of the student’s average grades from their first and second trimester. It then announced 10,000 extra university places to accommodate the higher number of pass grades.

In the Netherlands, the education minister announced in June that final central exams were also canceled. Students were awarded grades based on their school exams, which they had until June to complete, with resits taking place after that.

Newspaper Algemeen Dagblad reported that a third of secondary schools awarded all exam candidates a diploma this year, at least five times more than normal, which was attributed to extra study time and more resits. A spokeswoman for schools’ representative body VO-raad said: “This group of students had to take school exams under unexpected and difficult circumstances.”

In Italy, high school students took oral instead of written final exams, with social distancing and mask-wearing enforced, except during questioning.

International Baccalaureate examinations were also canceled, and the governing body confirmed Monday that no student would receive a grade lower than ones they had been predicted.

Additional reporting by Lauren Kent.