London (CNN) — Racism in Britain may attract less global attention than in the United States, but it is no less present – and Black Britons say it is past time for the country to face up to its colonial history and act to stamp out racial inequalities.

The police killing of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, in Minneapolis sparked global protests over police brutality and racial inequality despite an ongoing pandemic which has had a disproportionate impact on ethnic minorities in the UK and US.

In Britain, where public trust in institutions has been eroded by examples of systemic racism over decades, thousands have turned out to join Black Lives Matter protests despite pleas from the government for people to stay home.

And an exclusive CNN/Savanta ComRes poll reveals a divided nation, where Black people are twice as likely as White people to say they have not been treated with respect by police. Black people are also about twice as likely as White people to say UK police are institutionally racist – among White people, just over a quarter believe it.

Exposing further division, nearly two in three Black people say the UK has not done enough to address historical racial injustice, twice the proportion of White people who say that.

The CNN poll has been released as the UK marks Windrush Day, introduced in 2018 to celebrate the arrival on June 22, 1948 of the Empire Windrush. The ship carried the first large group of Commonwealth citizens from the Caribbean to Britain – at the invitation of the government – to rebuild the country after World War II.

But the Windrush generation and their children say they continue to suffer as a result of policies pursued by Conservative governments. Some lost their jobs, while others were evicted from their homes or faced deportation after decades living in Britain legally.

Glenda Caesar, who traveled with her parents from Dominica to Britain as a baby in 1961, says she suddenly lost her job as an administrator with the National Health Service in 2009 as she was unable to provide the necessary documentation. She fell into debt, unable to pay her bills without a wage, and nearly lost her home, she said.

A decade on, now aged 58, she has been unable to find another job despite being given British citizenship shortly after her plight was highlighted in the media. Her son, who was born in Britain in 1988, was also given citizenship.

“I was fighting for myself and for my son at the time – that was the thing that hurt me the most,” she told CNN. “Why should I have to fight for his right to be in this country when he was born here?”

Caesar, who spoke at protests this month in the east London neighborhood of Hackney where she lives and the Essex town of Southend, has, however, been heartened by the number, diversity and youth of the demonstrators she’s seen.

“I think it’s good for the world because now people are understanding what us, as a community, what we’ve been saying for a very long time. Where we haven’t had the justice that we’ve always been searching for but now everybody has come together,” she said.

She thinks others are now ready to stand up for what they believe in. “If we see a young Black man being surrounded by police and they are arresting him, people are now stepping forward and asking what’s going on,” she said. “If we turn our backs it could be another George Floyd and I think we’ve had enough. I feel safe – semi-safe – with my grandchildren growing up because at least I feel people will be looking after them.”

But she is less positive about the outcome for her and others caught up in the Windrush scandal, saying “we are still waiting” to be properly compensated despite the government apologizing for its actions.

She was offered a payout of a little over £22,000 ($27,200) in December under the government’s Windrush Compensation Scheme but – despite her continued difficult financial circumstances – turned it down as she felt it was insultingly low.

“So far 12,000 people have been given documentation to confirm their status, more compensation payments are being made every week and in the case of Ms. Caesar we are working with her representatives to review and resolve her claim,” a Home Office spokesperson said in a statement to CNN.

“The Home Secretary has been clear that the mistreatment of the Windrush generation by successive governments was completely unacceptable and she will right those wrongs.”

CNN’s poll found that 55% of Black people do not trust the government not to repeat something like the Windrush scandal again, while a majority say the Conservative Party is institutionally racist. CNN has sought comment from the Conservative Party and the government on the poll results.

Policing has long been the sharpest focal point for concerns over racial injustice in the UK. The government-mandated Macpherson inquiry in 1999, into the botched investigation of the murder of Black teenager Stephen Lawrence, who was killed in a racist attack by White youths in 1993, found that London’s Metropolitan Police was “institutionally racist.” The current Met Police Commissioner, Cressida Dick, insisted in 2019 that the “toxic” label no longer applied to the force.

But despite changes sparked by the Lawrence case and landmark Macpherson inquiry, Black people and other ethnic minorities in Britain are still disproportionately represented when it comes to police checks (known as stop and search), imprisonment, and deaths in custody.

According to UK government figures, between April 2018 and March 2019, White people were subjected to stop and search at a rate of 4 per 1,000, compared to Black people who were stopped and searched at a rate of 38 per 1,000.

Black Britons say their own experiences, and those of others in their communities, highlight disparities in treatment and fuel distrust.

Five Black British friends gained global fame after a picture of one of them carrying an injured White man to safety from the middle of the crush of a violent London protest went viral. Clashes broke out as far-right groups targeted Black Lives Matter demonstrations. The White man was later confirmed to be a former police officer.

Patrick Hutchinson, the Black man who carried him from the scene, said he helped the injured demonstrator because he did not want the main message of the protests to be overshadowed by one moment of violence.

In an interview some days later, he told CNN he believed the police to be institutionally racist.

“There may be individuals within the system who are trying to do a good job but as a collective they are racist,” he said.

Pierre Noah, another of the five friends, said the situation with regards to policing in Britain was “a mess” and that everyone, from the top down to the grassroots, needed to be educated on the issue.

“Do we feel protected by police? Not at all. I don’t think the police are quite sure how to approach our community,” he said. “They haven’t been educated enough how to deal with us in the community.”

“From when I was young to the kids now, honestly, from my heart, every day I pray for them. It’s gone backwards. It’s worse and it shouldn’t be the case.”

Asked what he thought the police see when they look at him, Hutchinson replied: “Color, race. Color – first thing they notice and that should be the last thing they notice.”

In response to the protests, Prime Minister Boris Johnson promised a review of racial inequality in Britain. But critics say he could instead implement the recommendations made in numerous past reports going back decades.

Opposition Labour Party politician David Lammy, who published a comprehensive review of racial inequality in the criminal justice system in 2017, told Johnson he “needs to stop the dither and the delay,” tweeting, “Young and old, black and white, rich and poor, the country is crying out for action.”

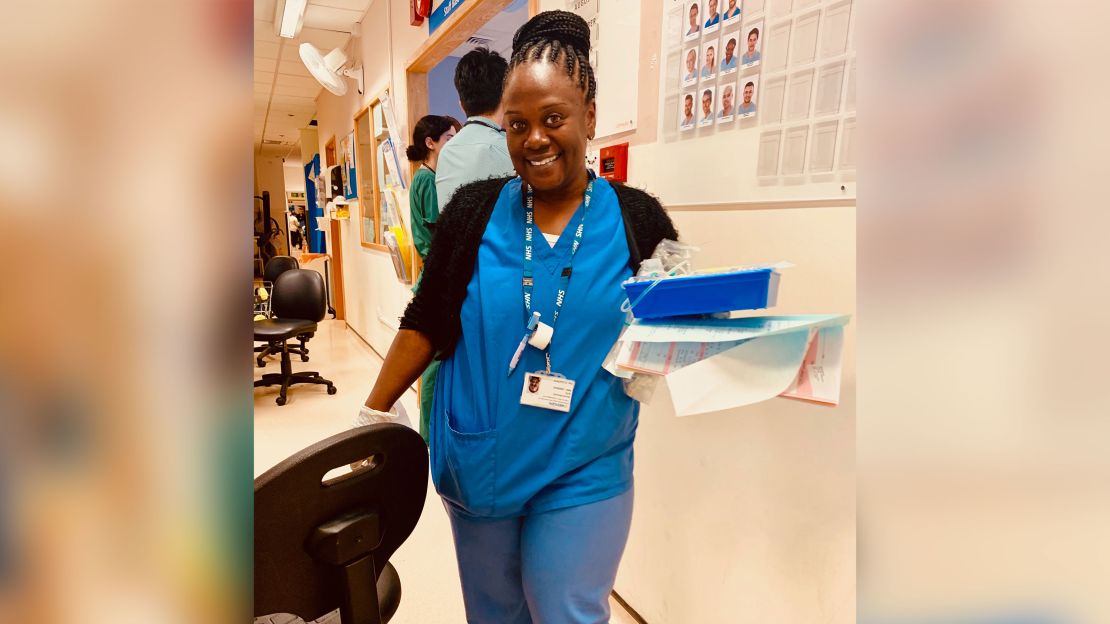

Nurse and entrepreneur Neomi Bennett, from London, was awarded the British Empire Medal for services to nursing in 2018 and met with the Prime Minister in January this year. But she too says she has been impacted by her encounters with Britain’s justice system.

The Guardian newspaper detailed Thursday how police officers approached Bennett one night in April 2019 in southwest London as she was in her car, saying her front windows were tinted too dark. She says she was too intimidated and scared to get out of the vehicle as repeatedly instructed. After several minutes of increasingly heated exchanges, she was pulled from the car and ended up under arrest and in a police cell overnight.

Bennett, 47, was found guilty in September of resisting and obstructing the police, but her conviction was overturned last month after she lodged an appeal which was not contested. She now intends to pursue a civil claim against the Metropolitan Police for wrongful arrest, among other charges.

“I think that the police approached me because they saw a couple of Black people sitting in a car. I believe I was racially profiled,” she told CNN.

A Metropolitan Police statement said the force had received a number of complaints relating to this incident, one of which remained under assessment.

“A complaint regarding discriminatory behavior, incivility, neglect of duty and use of force found no case to answer for. The complainant appealed this decision via the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) and they decided the appeal was not upheld. Due to the current complaint, we cannot go into any more detail at this time.”

Bennett said seeing what happened to George Floyd had pushed her to go public despite the acute embarrassment she says she feels about her own experience.

“When I watched that, I was in tears, I was beside myself, because it was so reminiscent of that time in the cell, the power that the authorities have got,” she said.

“As a Black woman in this country, if you say ‘it’s a race thing’ or if you say ‘it’s because I’m Black’ you are instantly shut down and told you have a chip on your shoulder. When this happened, it was too clear.”

Her grandparents were part of the Windrush generation, arriving in Britain from Jamaica in the 1960s to give their family greater opportunities.

“I am so grateful for that and I’ve never taken my Britishness for granted,” she said. “I’m proud to be British, but to be constantly faced with these microaggressions and then spend the night in a cell, it was like ‘I cannot keep it to myself anymore.’”

Bennett also worries for her two sons, one 24 and the other 29, both of whom have recently been stopped by police, she said.

The nurse, who suffered racial abuse while growing up in London, hopes the protests will mark a pivotal moment. “It just feels like the racism has reached a tipping point in regards to the injustices that we are seeing play out before us in front of our eyes,” she said.

“It seems like for a Black person in the UK, life is constant fighting. There are so many barriers, if you want to achieve anything you have to fight.”

So what does Britain need to do to change?

CNN’s poll has shown how sharply the nation is divided along race lines, whether it comes to policing, representation or history.

Protesters’ demands for statues commemorating people who profited from the slave trade to be toppled have highlighted a wider issue: that too little is done to educate many Britons about their nation’s colonial past.

CNN’s polling found Black people are twice as likely to support the removal of those statues as White people.

“I don’t believe we should have slave owners looking over us because that’s why we are in this position right now. Why would we idolize slave owners?” Caesar said.

“We need to start putting Black history on the curriculum so children who are growing up don’t need to ask us awkward questions. They already know about the Tudors and so on – they need to know about our history as well.” She believes more training for police on the subject would improve relations too.

Many believe there also needs to be greater representation of minorities in the cultural environment shaping people’s everyday lives.

Black people are more than twice as likely as White people to say there is too little representation of Black people in film and television, according to CNN’s poll, with two-thirds of Black people saying that and a quarter of White people.

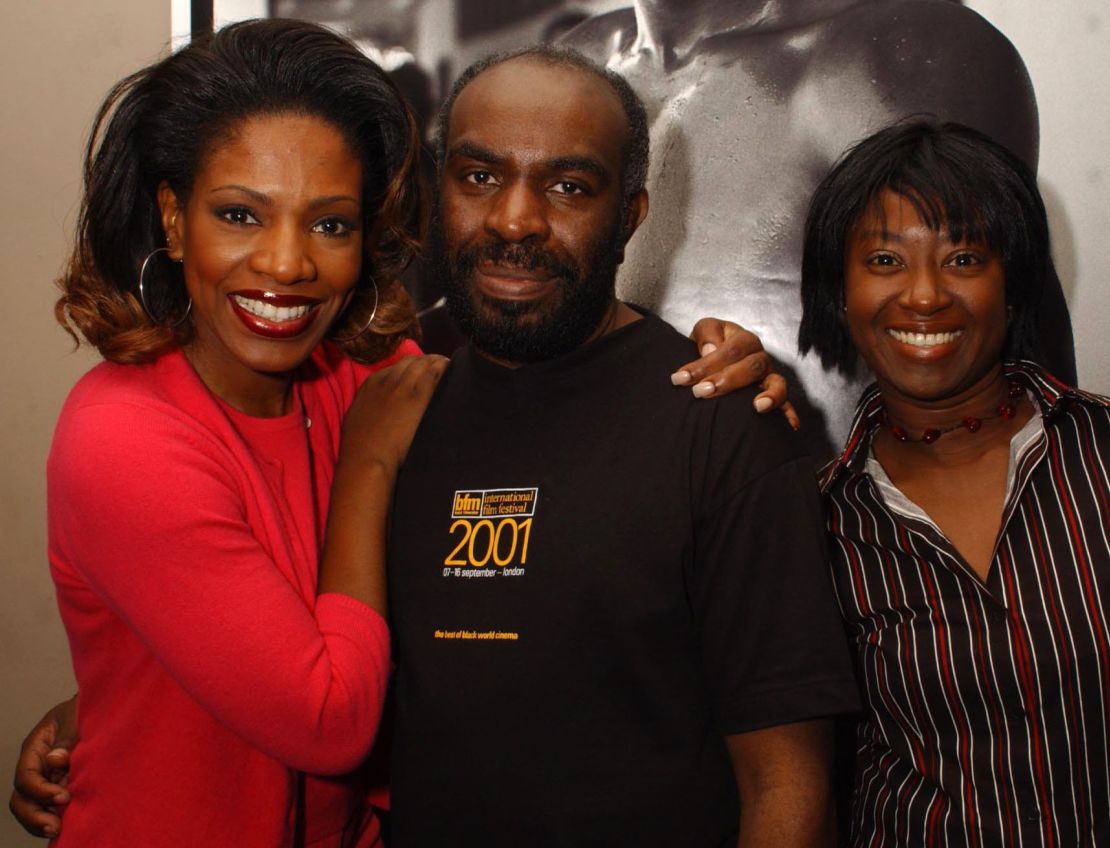

Filmmaker Menelik Shabazz, who was born in Barbados and moved to Britain at the age of five, said the current moment could give new energy to those calling for greater representation but cautioned that previous initiatives over the four decades he has spent in the industry had resulted in little change.

My Black Life Matters

Shabazz, whose 1981 debut “Burning an Illusion” was only the second feature film by a Black director produced in the UK, encountered so many obstacles in finding funding for other film and TV projects that for years he turned his focus elsewhere, including establishing Black Filmmaker Magazine.

He believes there is too little diversity in senior ranks, which helps perpetuate racial stereotypes, such as portraying young Black men in relation to crime.

Shabazz spoke to CNN from Harare, Zimbabwe, where the 66-year-old now plans to spend more time than in England.

“It’s a signature of my tiredness at having to keep fighting, having these battles and having to get these things done, and when your vision and your world isn’t seen as important or significant,” he said of the move.

“The way in which the media presents Black people informs the wider society, and it then plays out in day-to-day situations with Black men in particular – women too, of course, but Black men are at the front end in so many ways. You have to look at what is in the media, what is the education narrative that’s in schools, in terms of colonial empire. It’s a sense that our story has no value, so we can then be manipulated and ignored – and the Windrush scandal is another example of that scenario.”

Piers Harrison-Reid, a nurse and performance poet based in the east of England, wrote a poem for CNN to mark this moment.

“And if we aren’t heard with a knee, or with a raised fist, how else can we resist?

“I think the greatest trick racism ever pulled, was convincing England it doesn’t exist.”

CNN’s Gabrielle Smith, Tara John, Alex Platt and Mark Baron contributed to this report.