Remnants of the Berlin Wall in Germany still stand as a reminder that freedoms have always been hard won. Today, part of the wall has been painted over with a mural of George Floyd and the words “I can’t breathe,” another reminder of how quickly freedoms can be taken away.

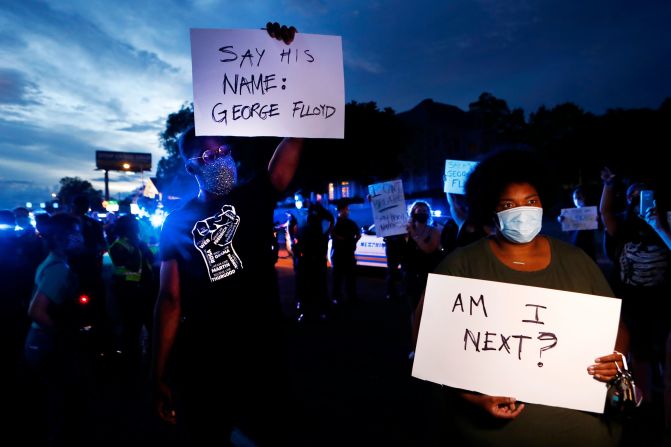

The harrowing video of Floyd, an unarmed black American, meeting his death as police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck for more than eight minutes has sent shockwaves around the world, mobilizing protesters across Europe and Africa, and as far away as Australia and New Zealand.

But beyond the death of yet another black American at the hands of police, US President Donald Trump’s response to it has further infuriated people and raised an important question: Is the US still the world’s moral guardian?

This week, at least, the answer is a resounding No.

“Sickened,” “shocked and appalled,” “horror and consternation” – these are words we’re used to hearing from US presidents and diplomats to condemn despotic regimes. But these are from leaders in the UK, the European Union and Canada, respectively, to describe Floyd’s killing.

“We support the right to peaceful protest, unequivocally condemn violence and racism of any kind and call for a de-escalation of tensions,” said the EU’s high representative, Josep Borrell, on Tuesday.

Few leaders have dared to criticize Trump by name, but Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez in parliament on Wednesday gave perhaps the strongest condemnation of the US government from an ally.

“I stand in solidarity with the demonstrations that are happening in the United States. Because obviously we are all very concerned about the authoritarian debate and those authoritarian ways that we are seeing as a response to some demonstrations,” he said.

At Lafayette Square across from the White House, police on Monday shot at protesters with rubber bullets and pepper-spray projectiles. One was seen beating an Australian journalist with a baton. Another shoved her cameraman with a shield and punched him in the face.

They are scenes reminiscent of the 2013 Gezi protests in Turkey, as the Islamic world’s celebrated democracy rapidly slid down the path toward authoritarianism. And they are particularly jarring to see in the US, a country where the freedom to protest peacefully is enshrined in the Constitution, a seminal document for the world’s legal architecture on human rights.

Just as startling as the crackdown itself was the justification for it. The police appeared to have used such force simply to clear a path for the President to stage a very unsubtle photo-op, waving a Bible in front of a church.

“There’s nothing that can justify the kind of force the police have been using, and it departs significantly against international human rights standards around the right to protest and the right to freedom of assembly,” said Michael Hamilton, an expert in public protest law at the UK’s University of East Anglia.

International human rights law obliges police to protect and facilitate peaceful protesters, he said. “The footage that everybody has been watching shows that blatantly is not what’s been happening.”

At a time where most leaders would call for national unity, Trump has threatened to use the military across the country to achieve “total domination,” branding protesters as “thugs,” even “terrorists.”

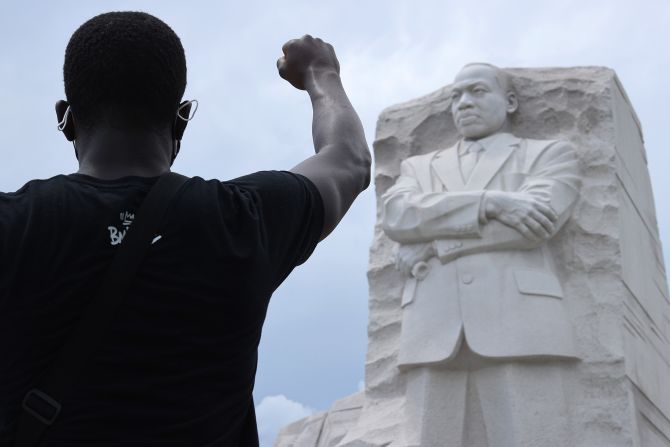

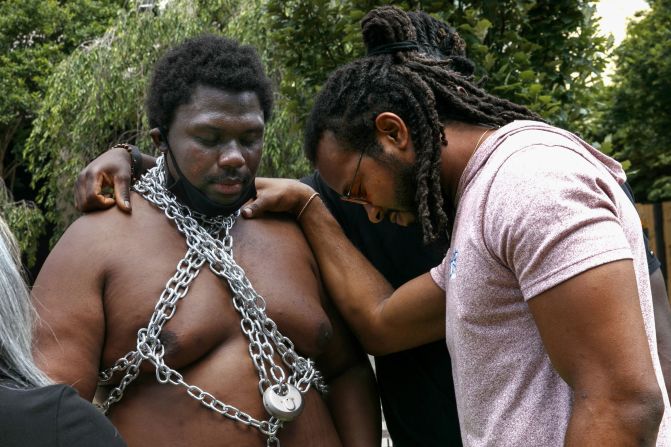

In pictures: A racial reckoning in America

Trump’s former defense secretary, James Mattis, slammed the threat in scathing remarks, saying: “We must reject any thinking of our cities as a ‘battlespace’ that our uniformed military is called upon to ‘dominate.’

“Militarizing our response, as we witnessed in Washington, D.C., sets up a conflict – a false conflict – between the military and civilian society.”

China media mock US: ‘I have a dream, but I can’t breathe’

As Hamilton points out, a US that orders militarized policing on protesters is likely to “find it difficult to sustain its criticism” of other countries using similar or even heavier-handed responses.

That dynamic is already playing out. China, Iran and Russia have seized on the moment to justify their own use of excessive force against its people, advance their own interests and ridicule a rival that they have traditionally seen as a stern and patronizing parent.

Editor-in-chief of China’s state-owned Global Times, Hu Xijin, has sent a flurry of tweets pointing to the hypocrisy of the US. Washington last year passed a law that would allow for sanctions against Chinese officials violating human rights in Hong Kong. More recently, it has censured China’s security law, aimed at quelling protests and possibly allowing the Chinese military to operate in Hong Kong, which usually enjoys more freedoms than mainland China.

“I have a dream, but I can’t breathe,” Hu wrote in one post, sharing a cartoon of a lighthouse and beacon adorned with the American flag crushing black men in suits.

He even used the chaos to suggest the US should stop criticizing China over its brutal crackdown on pro-democracy protesters at Tiananmen Square in Beijing, 31 years ago this week.

“The US repression of domestic unrest has further eroded the moral basis to claim itself ‘beacon of democracy’. The era that the US political elites could exploit Tiananmen incident at will is over.”

Iran too has tried to turn the tables on Washington. Foreign Minister Javad Zarif on Twitter said, “US cities are scenes of brutality against protesters & press,” and after Floyd’s killing, he tweeted an anti-Iran White House statement, annotating it as if Iran were criticizing the US for “suppressing” American protesters and denying their frustrations.

Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova also called out the US for hypocrisy Thursday, mocking the White House by suggesting it should release a statement of condemnation against itself, as it routinely does for other countries.

“It seems to me that our American colleagues should now be somewhat distracted from the instructive tonality that they have been spreading over the years in relation to other countries, take a look in the mirror and then describe everything that they saw there in statements, like those they addressed to many countries of the world,” Zakharova told journalists.

“We presume that, in carrying out measures to curb looting and other illegal actions, the authorities should not violate the rights of Americans to peaceful protest.”

What the US has to lose

The US has been considered the free world’s leader for more than 70 years. It emerged from World War II a victor and superpower, building the world’s biggest economy and military.

As Great Britain retreated from the role, the US began investing in democratic institutions globally. Trump’s “America First” approach, however, has pulled much of that funding and effort out of those institutions, which gave the US a platform.

In late May, the World Health Organization became the latest to be abandoned by the US, its biggest single government donor, right in the throes of a pandemic. It only amplified criticism that the US was not playing along in the global response, let alone leading by example, as more than 100,000 people in the US have died from the virus.

But the US still seeks to take the moral high ground in global affairs when it’s in its interest to do so.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, for example, condemned China’s security law as a “death knell” for Hong Kong’s democracy. He was able to speak boldly as Washington-Beijing relations were tense anyway, with Trump blaming China for the pandemic.

The White House has been less vocal about rights issues in some allied countries, like Saudi Arabia. The CIA concluded that the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi was ordered by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, an allegation he denies. The Trump administration has a strategic partnership with Saudi Arabia in intelligence sharing, trade and the control of oil prices, and has been restrained in its comments over the killing.

The US’ credibility has taken another dent over the past two weeks. Current and former diplomats told CNN the events at home were “scary” and “heartbreaking” to watch – and also undermined their mission. A current State Department official said that America’s “moral standing is challenged.”

But the erosion of the country’s moral credibility didn’t begin with Trump. America’s so-called war against terror and the abuses that came with it, such as those in Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib, was a major turning point. Some of that was remedied under the Obama administration, but even then, the US continued to violate rights abroad as the wars trundled on.

Trump’s three years in office have expedited that erosion, in part by his failure to lead by example at home, said Rob Berschinski, who worked for the US State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor during the Obama years.

The bureau was formed in the 1970s to “champion American values, including the rule of law and individual rights” across the world, according to its mission.

“It’s going to take serious work to bring back the power of example that has worked so clearly to America’s advantage throughout the course of our modern history. I think a lot of people take that for granted, but we shouldn’t take it for granted because we’re seeing what it means to lose it in real time,” Berschinski said.

When the US did lead by example, the bureau had the leverage to help negotiate the release of political prisoners, help shield activists in harm’s way and devise policy against countries that violate human rights, he said. It also meant the country had a global network of allies that could serve US interests, including economically.

“When the US doesn’t lead by example – as when the Bush administration resorted to torture, for instance – America’s influence in the world is weakened. We’re seeing that problem in stark relief right now. Just this week, some of our closest allies in capitals like Ottawa and Brussels have criticized President Trump’s obscene interest in using the US military to curb protests. Diplomats in friendly capitals can’t trust that the United States will do the right thing, which has ramifications across all sorts of policy areas,” Berschinski said.

US allies sour

Those ramifications are not only in emboldened authoritarian states, like China, Iran and Russia. It also puts America’s friends in sticky positions.

In Australia, one of the US’ closest allies, people have marched on the streets to call for an end to police brutality against black Americans, an issue that resonates in a country where indigenous people are disproportionately incarcerated and many have died at the hands of police.

And the issue of US police battering the Australian news crew in Monday’s protest has caused a rare squabble between the allies. Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison has instructed his country’s embassy in Washington to investigate the matter, describing the clashes between police and protesters as “terrifying and horrible scenes.”

Elliot Brennan, a research associate from the United States Studies Center at the University of Sydney, said the footage of the TV crew being assaulted was difficult for Australians to watch, particularly considering police were acting on orders of the US government.

The changing dynamics in the US have also put Australia in a more vulnerable position. The US has traditionally been its biggest partner in terms of security, while the country is highly dependent on China for trade. But Australia and China are currently in a tit-for-tat row over Beijing’s security law in Hong Kong and its handling of the coronavirus pandemic.

“With tension between Australia and China on a knife-edge, the intense internal focus of the United States could not have come at a worse time to reassure the Australian public of its commitment to the alliance,” Brennan said.

In the Philippines, the convulsions in the US have also stirred incredulity. The country has a profound connection with the US, as the only country America ever colonized. More than 4 million people of Philippine heritage now live in the United States, and after Israel, it has the most favorable view of the US in the world, according to the Pew Research Center.

The Philippines’ political system was built on America’s. Its constitution is modeled on the US bill of rights and is an enviable safeguard for freedoms in the Southeast Asian region.

Despite those safeguards, the Philippines has a history of moving between democracy and authoritarianism. The current president, Rodrigo Duterte, has managed to wield extraordinary firepower to clamp down on the country’s drugs trade. Thousands have been killed under his orders for police to shoot dead anyone suspected of being connected to the trade.

Veteran journalist Maria Ressa, CEO of news website Rappler.com, said that although Duterte was worse than Trump in his use of force, the disregard for rights playing out in the US now will only vindicate his heavy-handedness at home.

“Trump is very familiar to Filipinos. Many people have observed that he and Duterte have many things in common – they are both sexist at best, misogynous at worst. They incite to hate and sometimes to violence, and they tend to divide and conquer, making it us against them, instead of providing a leadership that tries to unite and to heal,” she told CNN.

“But in general, Filipinos are stunned by what’s happening in the US. It is familiar to us – we have a president who tells police to shoot people dead – but this is the United States. It’s always been the guiding light, the values of democracy, the founding fathers’ declaration of independence. And for the last three years, we and the world have grappled with who takes global leadership. We are wondering, has democracy failed?”