It could be a chapter out of a science fiction book: Librarian becomes disease detective and tracks down deadly virus.

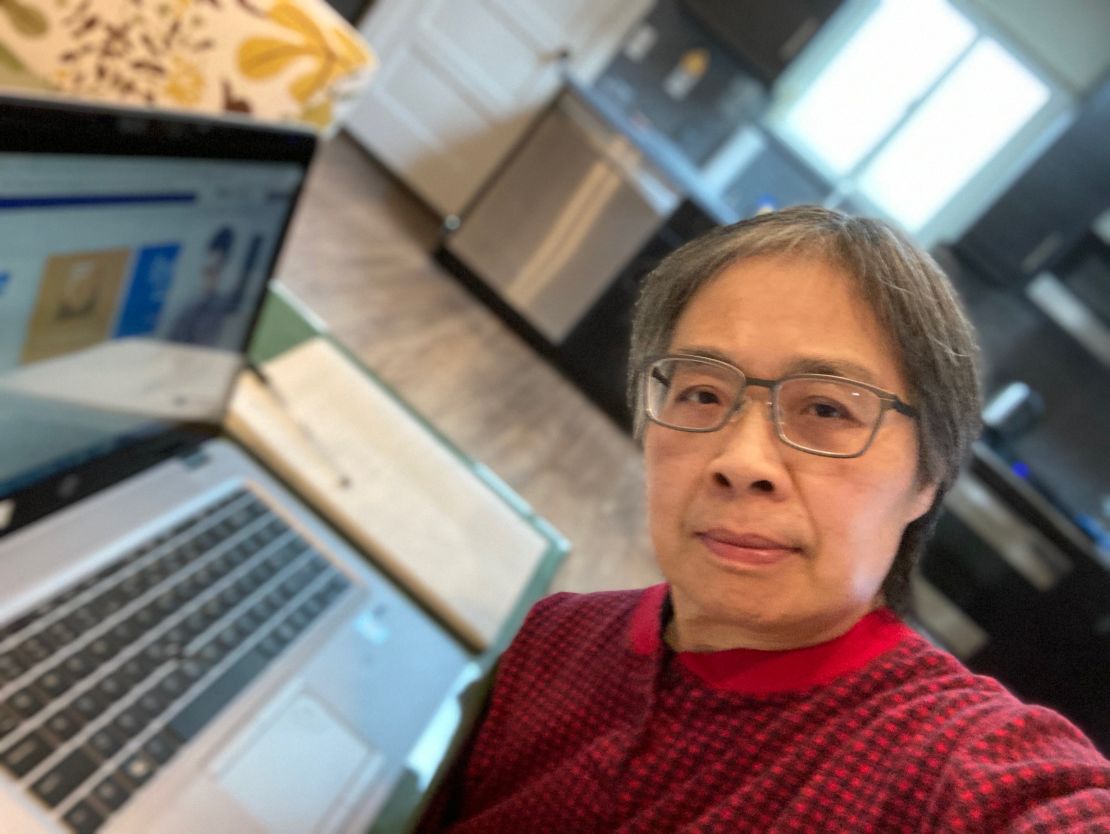

For 64-year-old Jensa Woo, she’s used to being surrounded by stacks of dystopian novels. But now she’s living it and writing her own story as a Covid-19 contact tracer ready to fight in the so-called “invisible war.”

“Even though I didn’t know what a contact tracer does, I thought, ‘I’m going to enlist,’” said Woo, a librarian with the San Francisco Public Library for nearly 30 years. “I think that the skills I have as a librarian are going to be pretty easily translatable into being a contact tracer.”

Contact tracers play a vital role in reducing the spread of Covid-19. The idea is to reach out by phone to people who have tested positive for the coronavirus or are presenting associated symptoms, and then track down other people who they may have exposed. Close contacts are considered at high risk of becoming infected and are asked to quarantine and be monitored for 14 days.

California was among the first states to develop a contact tracing program. In April, San Francisco’s Department of Health partnered with the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) to launch the initiative. Woo is among hundreds of city workers who have been recruited and trained.

“When we speak with the contact, we’re asking them personal questions like, living situation, demographic information, age, health and whether or not they have enough resources to isolate,” she said. “Typically we will ask, ‘Do you have enough food? Can you get food for that 14-day period? Do you have enough cleaning supplies?’”

Woo is scheduled to work four shifts, seven days a week. At the beginning of each four-hour shift, she is assigned a list of potential contacts who either live or work in the Bay Area. She uses a database to keep track of all the contacts she has interviewed.

“I will look to see if any are pressing because they are considered high-risk. We’re told to just prioritize in a particular way. So, I will attend to those first,” she said. “I will also look to see, ‘Oh, is this a cluster? Is there a family that’s involved?’ And then try to just group the calls, so that I don’t have to keep calling back and it’s the same number or it’s the same household.”

She told CNN that the majority of the people she calls appreciate the information.

“Overall, the contacts that I’ve spoken with are very receptive and they’re generally grateful that somebody is looking in on them and providing them with resources … if they need to self-isolate,” Woo said.

If they do need to self-isolate, Woo said, she makes sure they have what they need or connects them to city resources.

In March, Woo was furloughed from the San Francisco Public Library’s Merced branch. All city employees then became designated “Disaster Service Workers” and were reassigned.

Woo was among the first group of employees to complete training. She said the daily work is “quite intense but satisfying.”

“This is an unsettling time for many people. I think that this just helps to extend kindness and help and to serve other people,” she said.

Hiring an ‘army’ of contact tracers

As states reopen, governors talk about the need to hire an “army” of contact tracers to successfully contain the virus. A study from the Bloomberg School’s Center for Health Security estimated the US will need at least 100,000 contact tracers to stymy Covid-19 as all 50 states reopen.

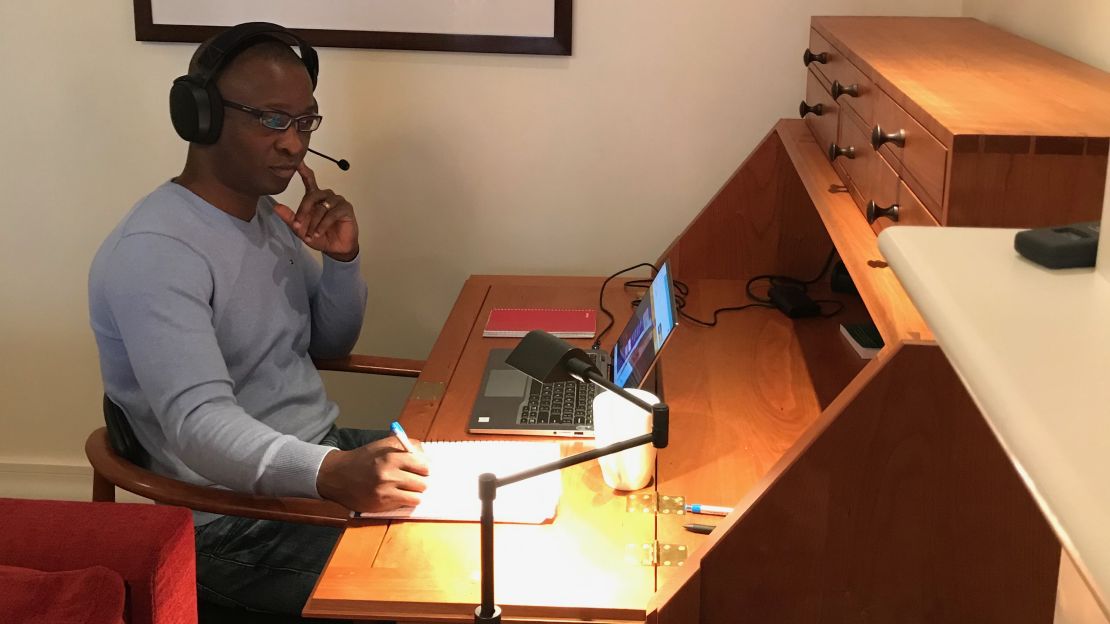

Alexander Miamen, 39, a Harvard Medical School student, knows the value of effective contact tracing after his experience performing it during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

“It was one (of the), if not the most, potent public health instrument in our attempt to blunt the spread of the virus,” he said.

He has been a Covid-19 contact tracer now for about three weeks with the Massachusetts Department of Health and Partners in Health, a nonprofit that partnered with the state to recruit and train more than 1,300 people. That’s only a fraction of the more than 48,000 who have applied through the organization.

Key to contact tracing is empathy and interpersonal communication skills, Miamen said. Contract tracers need to be perceived as an ally of the person they are calling, not an adversary.

“The first thing I ask them is, ‘How are you feeling?’ These people already know of the test results. It’s not breaking news to them, but we help them process that. It’s grief for them at some level. So empathize with them, and after that, try to educate them.”

Human contact tracers remain the heart of the process. Technology can also play a role, but there is nothing like a “listening ear” to help throughout this process, Miamen said. Apple and Google are developing new contact tracing technology using smartphones and Bluetooth technology to alert those who may have been close to someone infected, but he notes there could be limitations to technology.

Miamen, a refugee from Liberia who was later raised in Minnesota, is putting his skills to use in neighborhoods similar to where he grew up, speaking to immigrant families much like his own. He tries to engage with them by being relatable to his own upbringing and struggles. The immigrant population is “most often forgotten,” he said.

“This pandemic is not affecting everyone equally,” he said. “Most of these immigrants don’t even want to interact with the public health system because of the current political atmosphere and their distrust of systems.”

Covid-19 has magnified the systemic inequalities that persist in the United States. The coronavirus has disproportionately affected the health and financial well-being of Hispanics and African Americans.

Hispanic unemployment sits at nearly 19% – an all-time high, and higher than any other demographic. Black unemployment isn’t far behind, at nearly 17%. Both minority groups are also more likely to have pre-existing conditions, such as asthma and diabetes, which would worsen the health outcomes for someone infected by coronavirus. African Americans are dying at disproportionately higher rates from coronavirus compared to all other ethnicities.

“Immigrants are the ones working at the front line, they have a disproportional exposure to Covid-19. I care about everyone affected by Covid-19, but that’s the set of the population I empathize with the most, just because of my life experience,” Miamen said. “Bringing that to the table and being able to connect with them at that level has been indispensable.”

Employing the unemployed

Becoming a contact tracer presents an opportunity for some of the 38 million newly unemployed Americans. Proposals for a New Deal-style employment program have been floated around as a way to create millions of jobs.

Lissa Palermo Surgeoner is among those now out of a job. The 37-year-old mother of two has signed up to be a contact tracer from her home in upstate New York.

She applied through the New York Department of Health and is completing a free online training course through the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The program launched last week, and the state has an ambitious plan to hire between 6,400 to 17,000 contact tracers.

“I started training this week while my 1-year-old napped and my 3-year-old hid items around the house pretending to be the Easter Bunny,” she told CNN. “The first training video was brief and straightforward. I completed a quick assessment and moved onto the next lesson. Then I found the ‘eggs’ my child hid and started lesson two.”

She said her training will be completed sporadically during nap times and after bedtime.

“My husband and I will work out a schedule once the contact tracing is fully implemented in my area,” she said.

Surgeoner’s saga began March 20 when she was furloughed from her job as an attorney. As the outbreak spread and state lockdowns started, she ended up losing her job on April 30. Her husband, Brent Surgeoner, 38, also an attorney, lost his job too.

“It was just kind of a punch in the gut type of feeling,” she said. “We lost our health insurance, so that was kind of the catastrophic thing for us.”

The couple was able to apply for unemployment without any problems. Each week she receives $496 from New York state and $600 from the federal government. But the current federal subsidy is expected to end on July 31.

She’s volunteering as a contact tracer but has applied for a paid position.

“It wouldn’t match my salary as an attorney, but at this point I just want to contribute, and see what happens,” she said.

The coronavirus recession is hitting women the hardest. Women accounted for 55% of the 20.5 million jobs lost in April, with especially high unemployment rates for those ages 20-24 and over 50. The unemployment rate for women climbed to 15.5%, while the rate for men increased to 13%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Contrace Public Health Corps, an organization helping health departments across the country recruit and screen contact tracers, received more than 70,000 applications since April 21, and 66% of those applicants are women, CEO Steve Waters told CNN.

College senior Emalee Fico, 21, was looking forward to graduating from SUNY Oneota this spring. She was preparing to move to New York City and starta career in psychology, but she told CNN, “Covid-19 took away my last few months at school and prepping for the reality of adulthood.”

“I worked part time at my university in one of the dining halls which I relied heavily on to pay for bills and to make a savings before I graduated. I come from a small income, single-parent family and so I am fully responsible for my own expenses,” she said. “I filed for unemployment but have not received a clear deposit or confirmation that I can receive pandemic assistance or unemployment.”

Her professor referred her to New York’s contact tracing program, and after completing the training she just became a verified contact tracer. She could start as soon as next week.

“I’m happy to be a part of a movement to make a difference,” she said.

Woo, the Bay Area contact tracer, said she is moved by the people and stories she encounters as she hangs up the phone for each case.

“I answered all his questions and he answered all my questions,” she said, describing one call. “I was able to wish him well and to say, I would pray for him. And, he said, ‘Yes, please do.’

“And, so we hung up and then afterward I prayed for him and his family.”