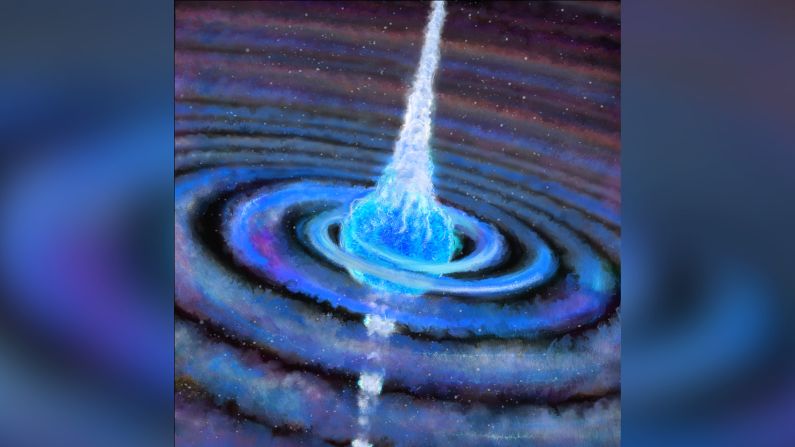

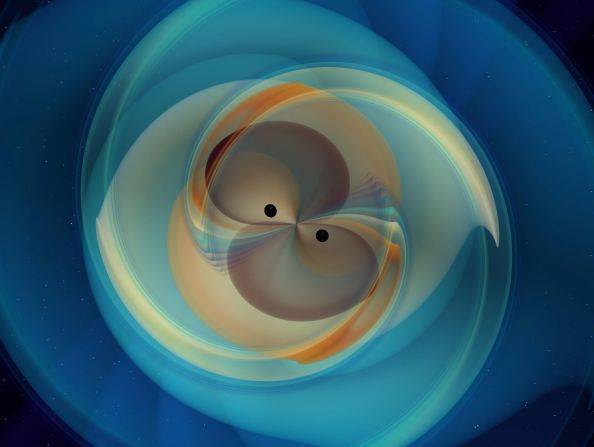

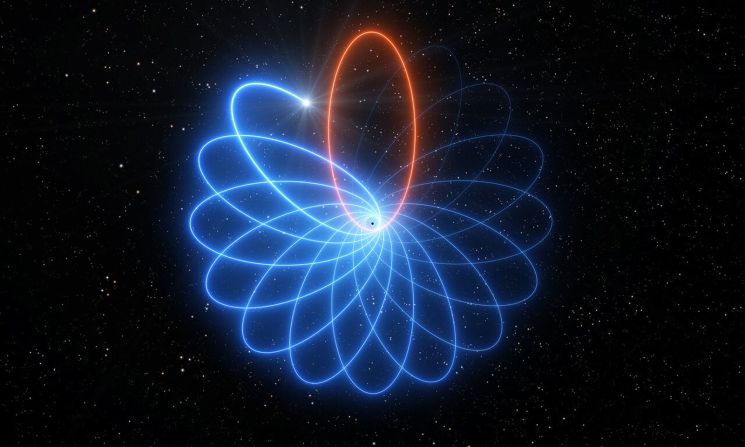

Astronomers have long studied supermassive black holes and smaller black holes that form when massive stars implode, but they have searched for intermediate-mass black holes for years.

Now, thanks to observations by the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have found their “missing link” to understand how black holes evolve. They were able to confirm the observation of an intermediate-mass black hole, known as an IMBH, inside a dense cluster of stars.

The study published this week in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Only a few other possible mid-range black holes have been found before. They’re difficult to detect because they’re smaller than the supermassive black holes that can be found at the heart of large galaxies. At the same time, they’re larger than black holes that form when stars collapse and die.

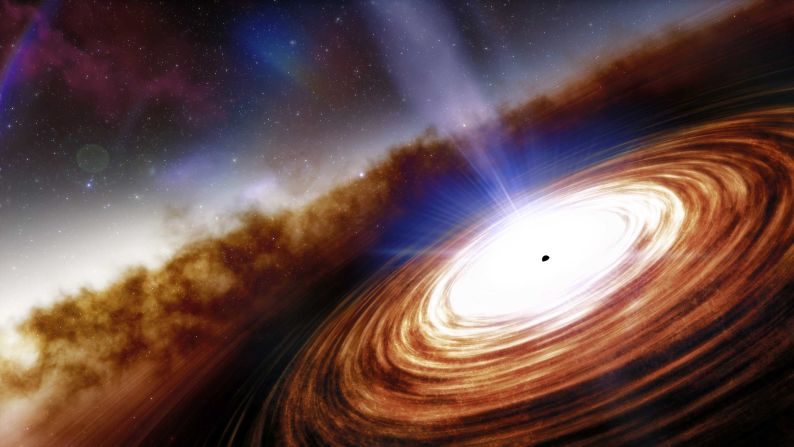

The nature of these mid-range black holes makes them harder to spot because they aren’t as active as supermassive black holes. They are also lacking the telltale gravitational pull on objects around them, which can create a detectable X-ray glow.

This particular black hole is more than 50,000 times the mass of our sun.

“Intermediate-mass black holes are very elusive objects, and so it is critical to carefully consider and rule out alternative explanations for each candidate. That is what Hubble has allowed us to do for our candidate,” said Dacheng Lin, principal investigator of the study and research assistant professor at the University of New Hampshire.

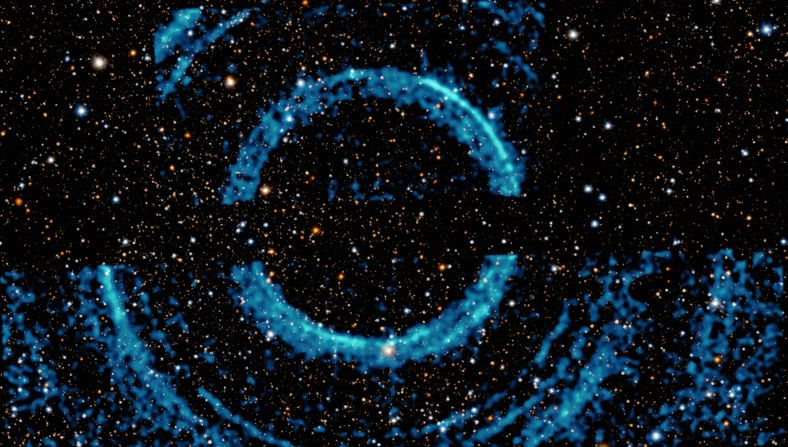

Hubble was used to follow up on observations previously made by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency’s X-Ray Multi-Mirror Mission. Both were launched in 1999 and have been providing X-ray observations of space ever since.

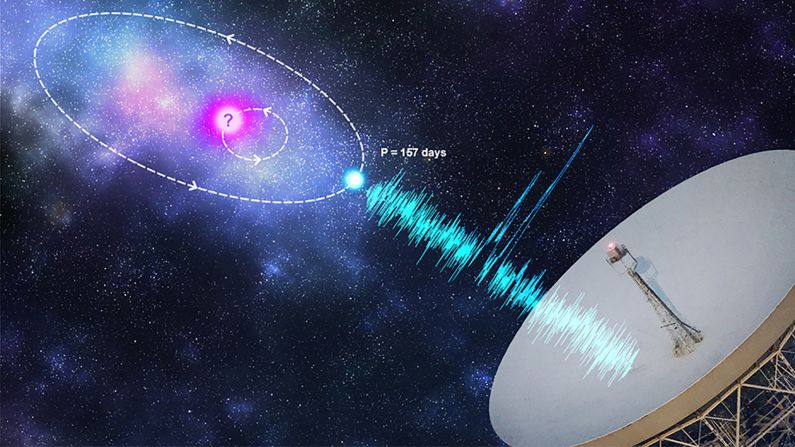

They first detected X-ray flares in 2006 that might signify a black hole, but astronomers couldn’t tell based on data if the signal was within our galaxy or outside of it.

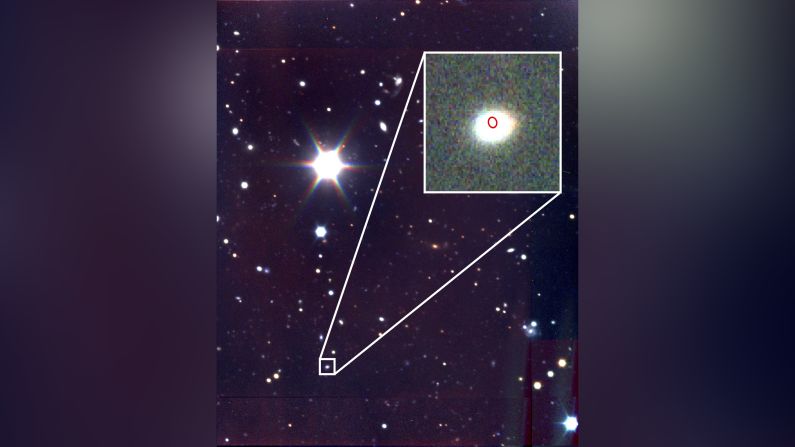

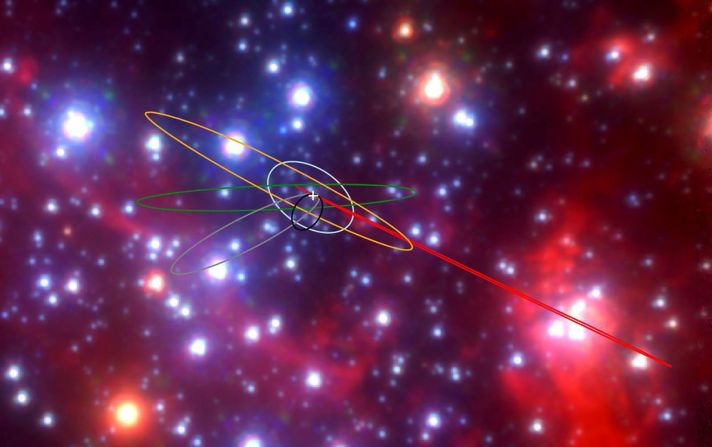

The signal source was named 3XMM J215022.4−055108. After ruling out its location in our galaxy or the possibility that it was a neutron star – the condensed remains of a dead star – the astronomers turned to Hubble.

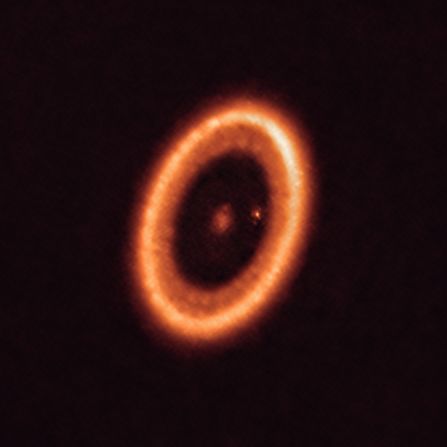

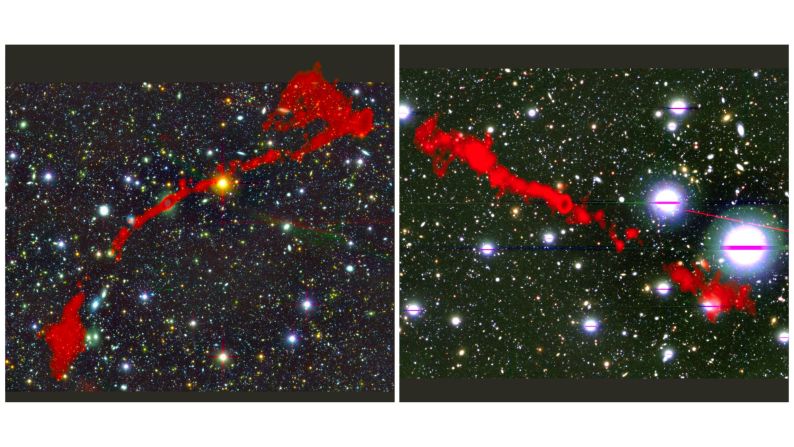

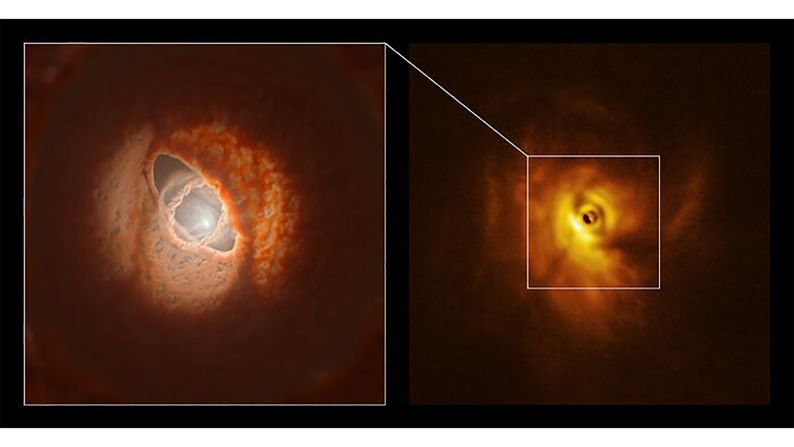

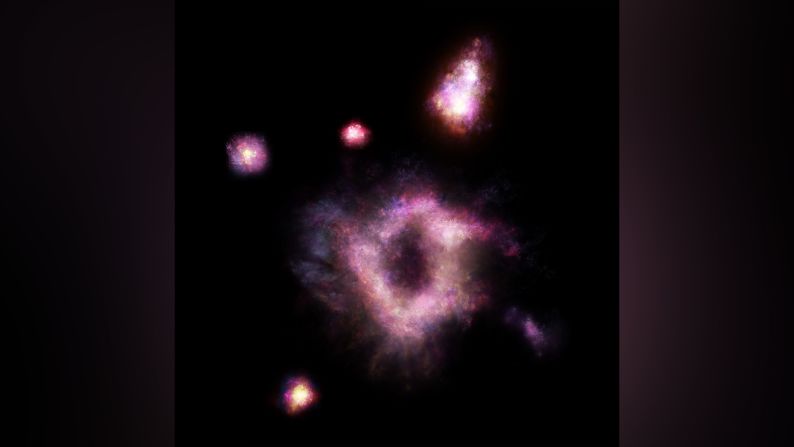

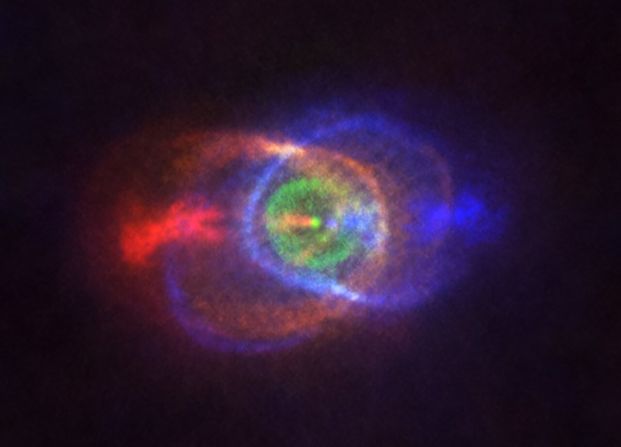

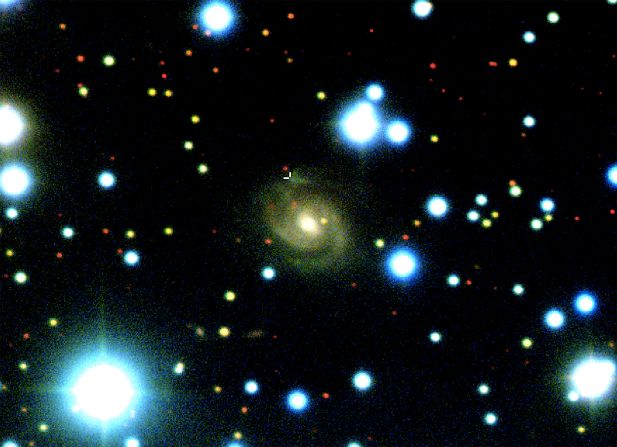

Aiming Hubble toward what they believed to be the source of the X-rays, the space telescope’s images revealed the signal was coming from a distant cluster of stars on the edge of another galaxy.

This excited the astronomers because it might be the perfect spot for an intermediate-mass black hole.

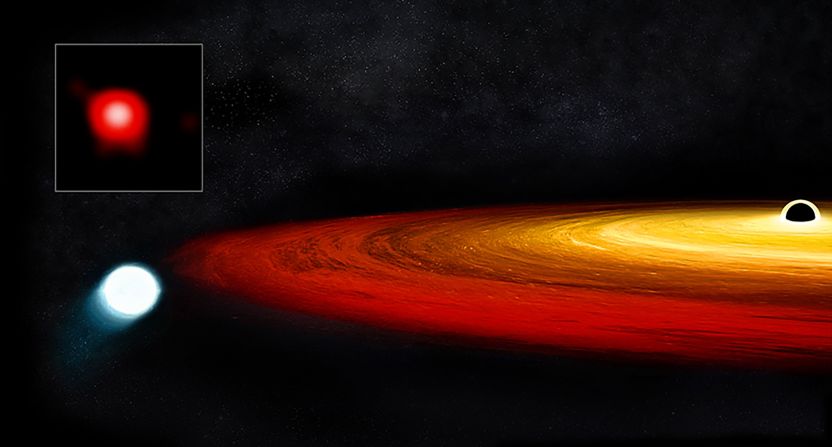

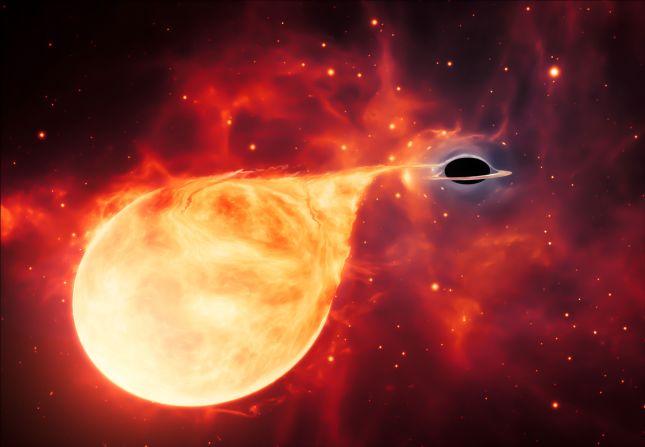

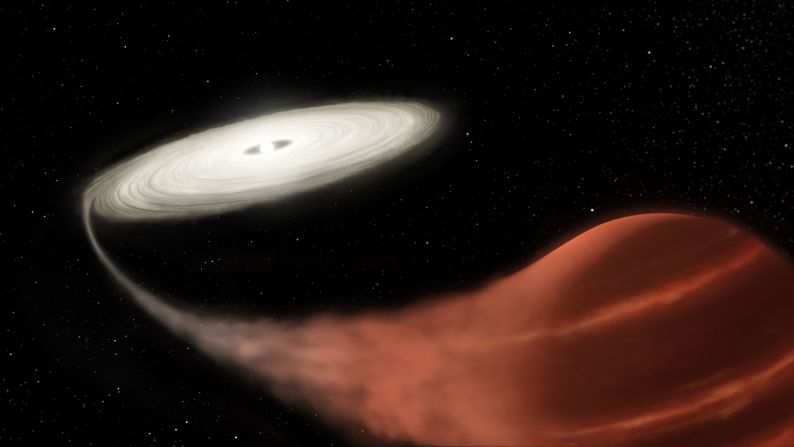

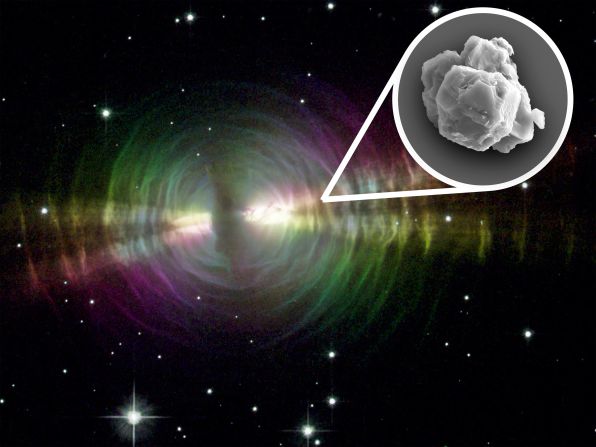

To confirm their finding, the astronomers looked back through X-ray data gathered by the X-ray Multi Mirror Mission. In the archives, they found evidence of an X-ray glow from a shredded star – something this black hole likely tore into and ate. This allowed them to estimate its mass and determine it was mid-range.

“Adding further X-ray observations allowed us to understand the total energy output,” said Natalie Webb, study co-author and astrophysicist at the Université de Toulouse in France. “This helps us to understand the type of star that was disrupted by the black hole.”

The star cluster that serves as the home of this black hole is likely what’s left of a small dwarf galaxy that was disturbed by a larger galaxy it orbits.

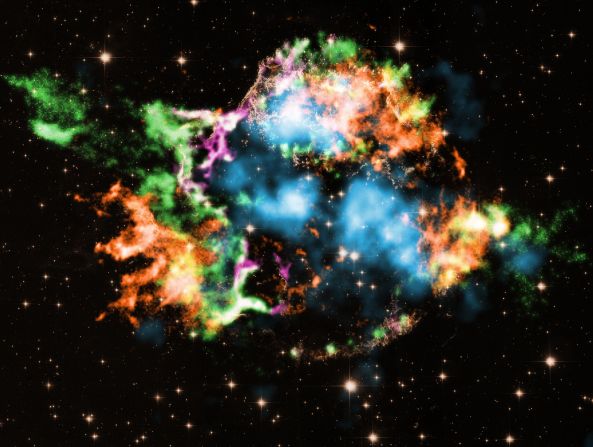

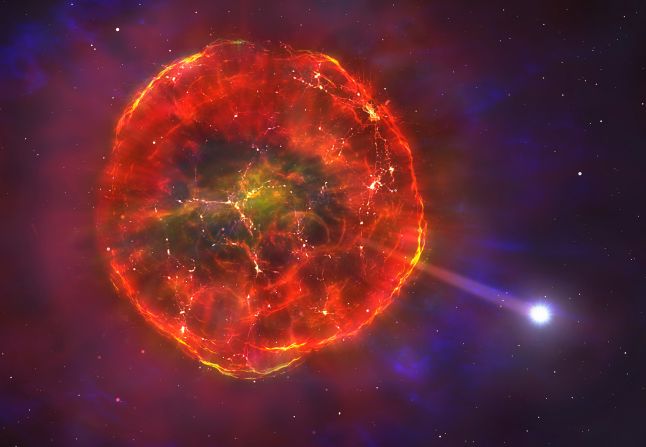

Now that they have confirmed an intermediate-mass black hole, astronomers are on the lookout for the signs of the next one, like a star disrupted by passing too close to the black hole.

More research can help them determine if supermassive black holes evolve and grow from intermediate-mass black holes, if they tend to favor star clusters and how they grow in the first place.

“Studying the origin and evolution of the intermediate mass black holes will finally give an answer as to how the supermassive black holes that we find in the centers of massive galaxies came to exist,” Webb said.