One of the biggest mysteries in piecing together the story of Mars’ past is a key question: Where did the water come from? Researchers may have found a large clue in tiny slices from Martian meteorites that fell to Earth, according to a new study.

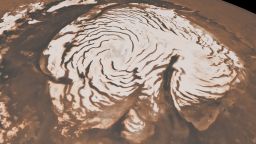

Mars was likely a warm, wet planet billions of years ago before its atmosphere was slowly stripped down and whisked out into space – leaving behind the thin atmosphere and frozen desert planet we know today.

But how did the water get to Mars in the first place? To understand that, researchers have to look at the layers of Mars. Like any planet, it has a core, mantle, crust and atmosphere.

Fortuitously, Martian meteorites contain samples of the planet’s crust. The crust is also where the largest reservoir is estimated to be on Mars, containing 35% of the total estimated water beneath the surface.

The two well-known meteorites are known as Black Beauty and Allan Hills, and researchers studied thin slices of them to look into Mars’ past, including how the planet formed and when water entered into the equation.

Their study published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

The Black Beauty meteorite, which is estimated to be two million years old, formed and broke off of the planet when a massive impact hit Mars and laminated pieces of Martian crust together. This effectively also captured material from different points in the Martian timeline.

“This allowed us to form an idea of what Mars’ crust looked like over several billions of years,” said Jessica Barnes, study author and assistant professor of planetary sciences in the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

When looking at the two meteorites, the researchers conducted a chemical analysis seeking out two types of hydrogen isotopes. Isotopes are the atoms that make up chemical elements.

They were specifically looking for“light hydrogen” and “heavy hydrogen,” because the ratioof these two isotopes can be used to understand the origin of water traces found in rocks.

For example, on Earth, scientists can study rocks and determine a similar ratio of hydrogen isotopes in all of them that translates to ocean water.

But those values differ wildly in Martian meteorites, and none of them have been similar, the researchers said.

The Black Beauty and Allan Hills meteorites suggested two different sources of water on Mars, based on their isotopes.

“These two different sources of water in Mars’ interior might be telling us something about the kinds of objects that were available to coalesce into the inner, rocky planets,” Barnes said. “This context is also important for understanding the past habitability and astrobiology of Mars.”

So how does that happen? It’s all about the ingredients that made Mars in the first place.

Planetesimals were the building blocks of the planets that form our solar system today. They’re made up of bits of gas and dust leftover from the formation of our sun. Over time, they grew in size and collided with one another, forming planets.

In the case of Mars, two different planetesimals with very different water content could have collided and never fully mixed, the researchers said.

This is very different than the previous theory about the formation of Mars, which suggested it was more like Earth. That theory stemmed from another Martian meteorite, but this one came from the planet’s mantle. The mantle is the rocky subsurface layer between the core and crust.

“The prevailing hypothesis before we started this work was that the interior of Mars was more Earth-like,” Barnes said. “So the variability in hydrogen isotope ratios within Martian samples was due to either terrestrial contamination or atmospheric implantation as it made its way off Mars.”

Earth had a global magma ocean that helped create its core and atmosphere billions of years ago, as well as the plate tectonics that shaped the continents. Now, researchers believe that Mars formed differently than Earth.

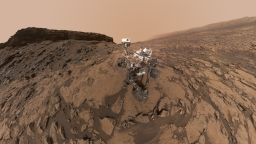

The meteorites, combined with other previous data about Mars, including observations by the Curiosity rover, revealed three things.

In the Martian meteorites, the crust remained much the same over time. The isotopes suggested the atmospheric changes they knew happened over time on Mars. And the crust samples were wildly different from the mantle below it.

“Martian meteorites basically plot all over the place, and so trying to figure out what these samples are actually telling us about water in the mantle of Mars has historically been a challenge,” Barnes said. “The fact that our data for the crust was so different prompted us to go back through the scientific literature and scrutinize the data.”

During that analysis, the researchers discovered two different types of Martian volcanic rocks called shergottites. Some were enriched, and some were depleted, meaning they contained evidence of water bearing different hydrogen isotopes.

Together, they match the strange story told by the Martian meteorites and Mars’ different water sources.

“It turns out that if you mix different proportions of hydrogen from these two kinds of shergottites, you can get the crustal value,” Barnes said.