A woman at an Australian supermarket allegedly pulls a knife on a man in a confrontation over toilet paper. A Singaporean student of Chinese ethnicity is beaten up on the streets of London and left with a fractured face. Protesters on the Indian Ocean island of Reunion welcome cruise passengers by hurling abuse and rocks at them.

The coronavirus risks bringing out the worst in humanity.

Never mind that Australia’s toilet paper supply is plentiful, that the Singaporean has no links to the virus and that not a single passenger on the Princess cruise ship that docked in Reunion was infected.

Irrational and selfish incidents like these are likely the exception, not the rule, but an everyone-for-themselves mentality – or each family, even each country – appears to be growing, putting into question the world’s ability to unite and slow the coronavirus’ spread.

Leaders of affected nations are scrambling to seize some control of the situation. They impose restrictive measures in their countries, inject money into their economies, and promise their health systems will somehow find the extra beds, doctors and nurses they will inevitably need.

Yet there seems to be little coordination between countries to address what is by nature a global challenge.

Face masks around the world are running out, as people who don’t need them hoard them. The US is stockpiling them, while South Korea, Germany and Russia, among others, have banned their export, to ensure their own people have enough.

India, which makes 20% of the world’s medicinal drugs by volume, has halted certain medicines from being exported. Yes, it is unable to source enough ingredients from China and can’t make its usual output, but it is also likely keeping them for its own people.

Populists point the finger

This pandemic has now claimed more than 5,000 lives, infected over 150,000 people and touched every continent, save for Antarctica, as it crosses geographical borders that have politically closed.

European leaders have met several times and it was only on Tuesday that they finally announced some coordinated action. It was aimed primarily at economic stimulus, rather than devising a much-needed gameplan to slow the virus’ spread across the region.

There is serious doubt that the usual economic tools will even work. During a health crisis, injecting money into economies doesn’t necessarily get people spending. Consumers travel and shop less, and on the supply side, factories and businesses are closing in countries like China, Japan, South Korea and Italy.

Italy, the worst-affected country outside China, complained the EU had been too slow to help, as it desperately needed more surgical masks and ventilators for patients, which it is now relying on China to provide.

EU leaders have chastized member countries for clinging to protective gear like face masks, as the 27-country bloc is supposed to be united and enjoy free trade.

The pandemic comes at a time when the world was already questioning globalization, emboldening anti-globalization arguments and the populist parties seeking greater isolation.

Italian far-right opposition leader Matteo Salvini called recently for the country to close its border.

“The infection is spreading. I want to know from the government who has come in and gone out. We have to seal our borders now,” he said in a video on Facebook in late February.

US President Donald Trump on Wednesday framed the outbreak as a “foreign virus,” blaming Europe for failing to act quickly enough, as he announced sharp restrictions on travel from more than two dozen European countries. On Saturday the ban was extended to the United Kingdom and Ireland.

Why humans can be selfish and irrational

Much of this each-for-their-own behavior comes from humans’ tendency to trust their feelings over facts, a way of thinking that is “evolutionarily ancient,” according to Paul Slovic, a University of Oregon psychologist, who studies risk perception.

There are two main modes of thinking, he explains: one an intuitive sense based on feelings, the other a more rational sense based on scientific reasoning, evidence and reason. It is the intuitive mode that dominates, according to Slovic.

“In the earliest days when we were evolving, there were plenty of dangers around, and those dangers were directly experienced, they were threats that we faced directly from threatening creatures or other tribes, it was all very direct and concrete. So these reactions based on feelings were very beneficial in helping us act quickly and to recognize friend from foe, it was us against them,” Slovic told CNN.

“Like if you heard a sound in the bush that might be a dangerous animal, you didn’t stop to reason about what was causing the sound – was it really a dangerous animal? – you just accepted the fact that it sounded scary and you got out of there. You moved fast. So our survival depended on testing your emotions and behaving quickly, and acting according to those feelings.”

Feelings, he said, are usually a useful guide that helps us make good decisions every day.

“It’s easy, it’s natural, fast – it’s a remarkable capability in our modern brain, except there are a few things it doesn’t do well, and one of those things is it doesn’t relate to statistics, or numbers, very well.”

This is playing out in the current pandemic, he said, as most of the information received through the media and officials are of the worst cases and fatalities. We aren’t computing well that the vast majority of cases are mild, even asymptomatic.

It’s unsurprising that some people might feel threatened by someone who comes from Wuhan, where the virus originated, or China, or another country that is prevalent, he said, because of the way the mind works.

“It’s a natural, protective response, which can be exaggerated and harmful to people who pose really a very low risk,” he said.

“But it’s an emotion that should be tempered by reason – we should say, what do we know about the probability that this group of people is really going to harm us in some way? What’s the severity of it? What does the data show? What does it say about the level of risk? What we see is that stigma can occur even when the risk is very low and the stigma is not warranted.”

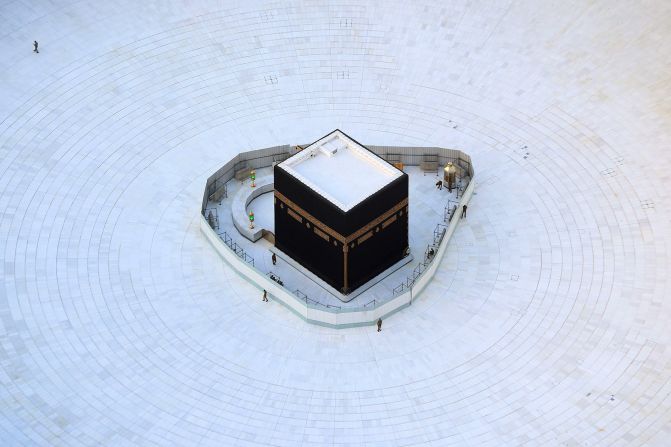

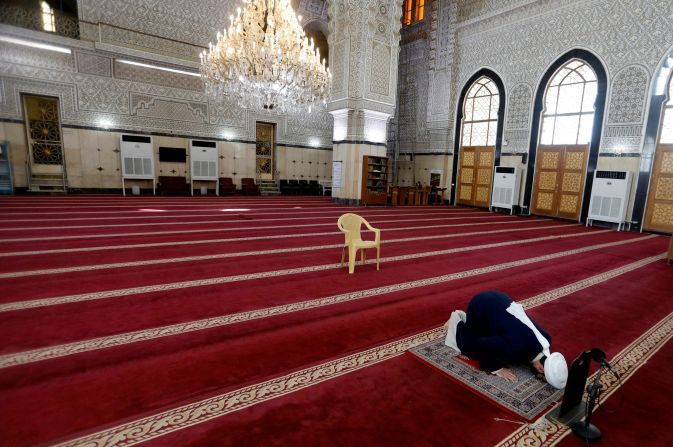

The coronavirus is leaving empty spaces everywhere

Actually, stockpiling isn’t always irrational

The world is not doomed quite yet. For all the examples of anti-social behavior, there has been pro-social action.

We can feel heartened by the doctors, nurses and other medical staff who are still showing up to work, often on the front lines, risking their own health for the greater good.

Cleaners are still working at offices, on trains and in schools and nurseries, doing their part in keeping people safe.

People are taking hand washing and sanitizing seriously – the sellout of hand gels around the world is testament to that – to prevent communal spread of the virus.

And stockpiling groceries may not be as selfish as it seems, according to techno-sociologist Zeynep Tufekci of the University of North Carolina.

Preparing for the virus “is one of the most pro-social, altruistic things you can do in response to potential disruptions of this kind,” she wrote in Scientific American.

She argues that being ready with grocery items at home could help stem the virus’ spread, if it means not needing to go out to supermarkets and if those stocks can be shared with more vulnerable neighbors who may be less organized. Keeping in good health and getting a flu shot will help keep pressure off healthcare systems, she said.

This pro-social behavior has happened in the past. World War II may have been the worst display of humanity in modern history, but it was also a time where much of the world banded together to fight a common cause.

It involved an extraordinary marshaling of resources and sharing of information, both between individuals and countries. Soldiers were often sent to fight on foreign fronts to support allies, even in cases where their own nations were not directly under threat.

Susan Michie, a health psychologist at the University College London who specializes in behavioral change, says that most people are inclined to act in pro-social ways when faced with a threat, as long as they feel they can rely on governments and society to provide for them and treat them equally.

“The problems arise when the demand for healthcare or food or medicine exceeds the resources,” she said.

“The last time in the UK felt this kind of threat was in World War II, and in fact, people were healthier than they had been for a long time – there were rations, and distributed much more equally. People really went the extra mile to help,” she said.

“It’s a very good example of ‘We’re all in this together.’ Then you were fighting a common enemy and now we are also fighting a common enemy, with this virus. We need to get that idea into the collective mentality.”