Before there were any cases of novel coronavirus confirmed in South Korea, one of the country’s biotech firms had begun preparing to make testing kitsto identify the disease.

On January 16, Chun Jong-yoon, the chief executive and founder of molecular biotech company Seegene, told his team it was time to start focusing on coronavirus.

That was before the virus sweeping China had been named Covid-19 and four days ahead of South Korea confirming its first case.

“Even if nobody is asking us to, we are a molecular diagnosis company. We have to prepare in advance,” he remembered thinking at the time.

Fast forward two months, and South Korea is among the world’s worst affected countries, with more than 7,800 people infected, and more than 60 deaths.

But one reason why South Korea might have a higher number of infections than other countries is its aggressive approach to testing.

While some nations have struggled to get enough test kits to diagnose suspected patients, South Korea has provided free and easy access to testing for anyone who a doctor deems needs it. The country’sCenters for Disease Control & Prevention (KCDC) says the country has 118 facilities that can test– and all report their results to KCDC. To date, the country has tested more than 230,000 people.

It has even rolled out drive-through coronavirus testing facilities, where motorists are met by health workers dressed in hazmat suits.

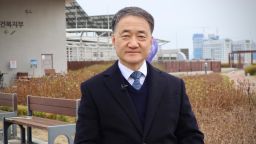

“Detecting patients at an early stage is very important,” South Korea’s health minister Park Neung-hu told CNN Monday. “South Korea is an open society and would like to protect the freedom of people moving around and traveling.

“That is why we’re conducting mass amount of tests.”

But to roll out tests en masse, a country first needs test kits.

A secret weapon

In the basement of Seegene’s headquarters in Seoul lies the key to the company’s coronavirus success.

There the company houses an artificial intelligence-based big data system, which has enabled the firm to quickly develop a test for coronavirus.

Tests known as assay kits are made up of several vials of chemical solutions. Samples are taken from patients and mixed with the solutions, which react if certain genes are present.

Without the computer, it would have taken the team two to three months to develop such a test, said Chun. This time, it was done in a matter of weeks.

By January 24, the scientists had ordered the raw materials they needed for the test kits. Four days later, they arrived. On February 5, the first version of the test was ready.

It was only the third time the company had used its super computer – rather than its research and development team working manually – to design a test. It had previously used the system to make diagnosis kits for urethritis, the inflammation of the urethra.The company was able to design the test using only the genetic details that had been released about the virus, and without having a sample of Covid-19.

And it didn’t require his teams to work around the clock. Only a few people needed to be involved, said Chun.

The next hurdle was getting the test approved for use. It can take a year-and-a-half to submit the necessary documents to South Korea’s authorities and get it approved.

This time, it took a week.

Lee Dae-hoon, who led the team of scientists working to develop the coronavirus test kit, has spent his whole life working on diseases. He’s never seen the KCDC approve a test kit so fast.

On February 12, Seegene got sign off, thanks to KCDC expediting the process. It was only then that the scientists only knew for certain that their test worked, as the government had evaluated the test using their own patient samples.

Getting the kit to hospitals

By mid-February, South Korea’s coronavirus cases had spiked dramatically. On February 23, the country’s President Moon Jae-in raised the country’s crisis alert to the highest level.

“We’re now at a watershed moment with the novel coronavirus and the next few days will be very critical,” Moon said in a televised address. “We need to identify the infected people as soon as possible and prevent the virus from spreading further.”

Following that, Chun made a snap decision. His 395 employees would drop all other work and focus on making coronavirus test kits. Production of the company’s 50 or so other products temporarily ceased for two weeks.

“Emergency operation means all of the divisions, you have to change your job,” he said. “All of our teams are focusing on coronavirus product development.”

That means micro molecular biologists with PhDs have had to drop research and development to take a seat on the assembly line.

“Some times (senior scientists are) doing packaging of the product. It doesn’t matter how they are educated, it doesn’t matter because we are crazy here,” said Noh Si-won, the executive director of corporate strategy.

Seegene is one of four domestic companies providing coronavirus test kits in South Korea.

But the company is also facing international demand from about 30 countries – including Italy and Germany – some of which are using Seegene’s products on patients, Chun said.

At first, Seegene struggled to meet demand, but now it is coping.

The firm is making about 10,000 kits a week and each kit can test 100 patients. So it is making enough to test one million patients each week, at a cost of under $20 per test.

Noh Si-won, the executive director of corporate strategy, said it is the first time he has seen the company manufacturing at this scale.

The company has three months’ worth of stock of other test kits, so it can meet demand for its preexisting orders for a month or two. But Chun said it was important for the company to continue making coronavirus test kits – and the need goes beyond financial gains.

“We have to be providing or contributing one way or the other to figure it out as soon as possible. That’s why (we supply to) the whole world,” he says.

What other countries are doing wrong

In other countries, the authorities have struggled to keep up with the demand for testing.

Chun says one possible explanation is that some places may be testing manually, rather than automatically.

All tests start with a nurse taking a swab or a sample from a patient. If the swab is tested manually, a scientist will use a pipette to put the assay kit onto the sample.

But in a growing number of places – including South Korea – scientists are using automatic testing.

Rather than a human mixing the solutions, the samples are instead put into a diagnostic machine.

Inside the machine, a robot arm pipettes the solution and mixes the liquids on a number of tests at once. According to Chun, this method takes only four hours to test samples from 94 patients – four times faster than the manual method. It also reduces the risk of human error or contamination.

The other thing that could be slowing some countries down is the type of test kits being used. There are three genes that can be tested for to confirm coronavirus – and Seegene’s kits are able to test for all three genes in one tube, said Chun. That’s not necessarily the case for all test kits.

Chun believes if the United States had access to Seegene’s system, the country could test 1 million patients a week. But for now, the US isn’t using the test on patients – it doesn’t have approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Chun wants to help health authorities overseas.

“The issue is they have no chance to test the people properly,” he said. “Without the proper diagnosis, nobody knows what’s going on.”