The novel coronavirus outbreak has been brutal for China and could plunge the country’s economy into its first contraction since the 1970s.

Economic activity sharply declined across the board in February as companies struggled to reopen for business or hire workers during a government-mandated shutdown, according to official and private surveys released in recent days.

Wednesday revealed shockingly bad news for services in the world’s second biggest economy. Chinese media group Caixin said its purchasing managers index for the sector plummeted to 26.5 last month from a reading of 51.8 the month before — the lowest figure recorded by the survey since it began in 2005. A reading below 50 indicates contraction, rather than growth.

“China’s economy is in a very bad way indeed,” said Kit Juckes, a strategist at Societe Generale.

That data — which mostly follows small and medium-sized companies — largely tracked with a government survey of primarily state-owned firms in the services sector released over the weekend. China’s factories also recorded their worst month on record in February, according to government and Caixin data, as companies face extended closures to contain the virus, or struggled to fill jobs because of travel restrictions.

“The virus outbreak has put the government into a difficult situation,” said Raymond Yeung, chief economist for Greater China at ANZ. “On one hand, the lockdown policy is the most effective way to contain virus spreading out. On the other hand, the health measures are hindering economic activity.”

The gloomy picture painted by the data is reinforced by evidence from coming from big companies. The world’s biggest brewer, ABInBev (BUD), said it had lost $285 million in revenue in January and February in China, while iPhone maker Foxconn (HNHPF) said Tuesday it didn’t expect production to return to normal until the end of March.

The fallout could be crippling for China’s economic growth this quarter. Macquarie Group chief China economist Larry Hu suggested that the country could be in for a historic economic decline.

The data “suggest that things are really bad and the government is willing to report that,” Hu wrote in a note after the official data was released at the weekend, adding that growth for the first quarter could come in well below estimates currently running at around 4% (down from 6% in the fourth quarter of 2019).

“It’s even possible that the government will report negative growth for [the first quarter], the first time since the end of Culture Revolution,” he added.

China’s economy contracted 1.6% in 1976, when Communist Party leader Mao Zedong’s death ended a decade-long period of social and political tumult in the country. Since then, China has boomed, growing at an average annual rate of 9.4% between 1978 and 2018 as it embarked on a series of economic reforms.

Hu wrote that China will likely enact more policy measures to help the economy, but added that it’s too early to expect a big stimulus package from Beijing.

UBS economists also suspect that China’s economy contracted in January and February, noting the poor PMI data in a Tuesday research note.

“The next two weeks will be critical to track the path of new confirmed cases of coronavirus and the pace of economic normalization,” wrote Ning Zhang and Tao Wang, economists for UBS.

Bad news for jobs

The recent data suggest that Beijing’s efforts to shore up employment this year are in jeopardy. China’s services sector represents about 360 million jobs and accounts for 46% of the labor market, making it the largest source of employment in the country.

Government authorities have been pushing hard to keep unemployment low, wary of the fallout that could happen otherwise. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang said last month that officials are “closely watching the employment issue and will try to prevent massive layoffs.”

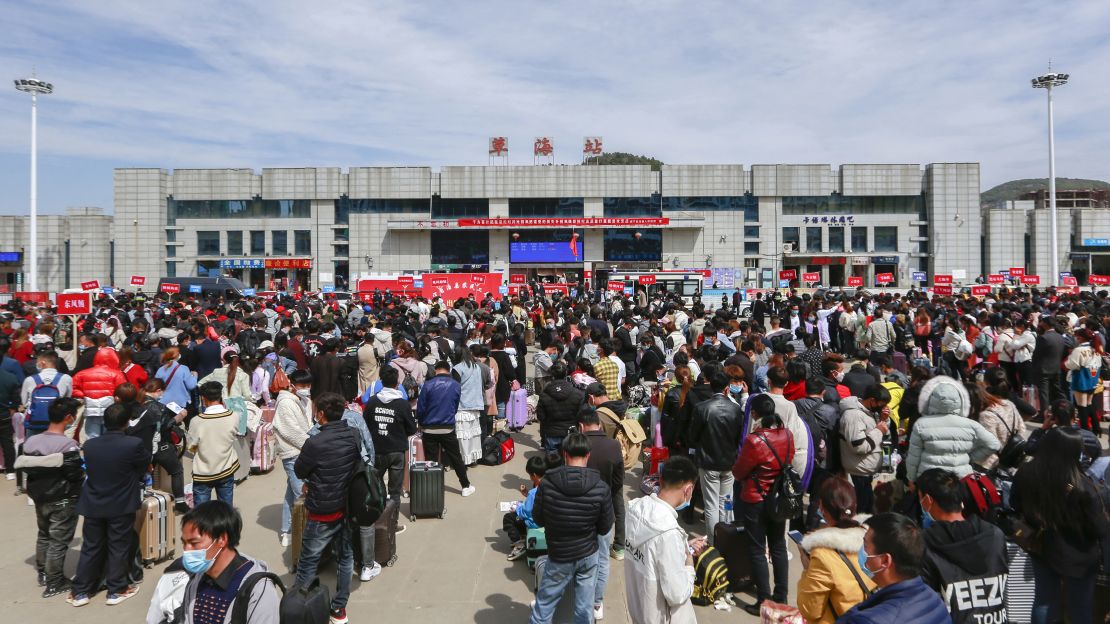

He also said stabilizing employment is the government’s primary task, and placed special emphasis on new graduates and migrant workers. China’s 290 million migrant workers are among those most exposed to a slump, since they often travel from rural areas to the cities to take on construction, manufacturing, or service jobs that would have been tough to find during last month’s widespread shutdowns.

Only 80 million migrant workers had returned to work by mid-February, according to the government.

In recent days, Beijing has also urged college students to join the army and ordered all public colleges to expand their advanced degree programs — efforts meant to reduce the number of job seekers.