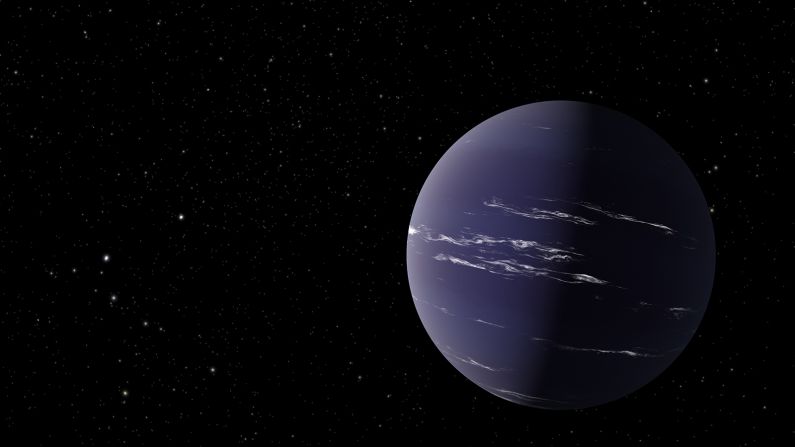

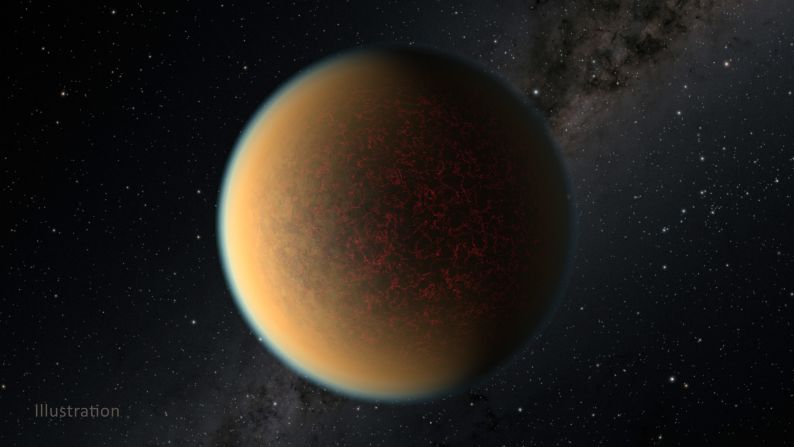

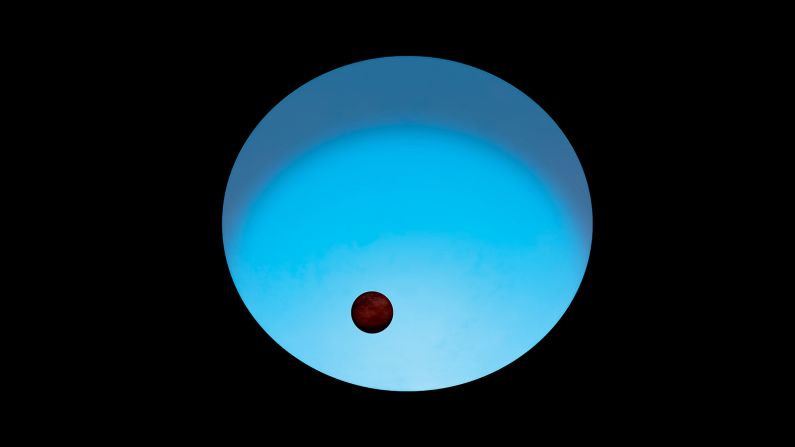

Cotton candy exoplanets sound like something from a futuristic version of “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” but the cute phrase is used to describe a class of planets found outside of our solar system called “super-puffs.”

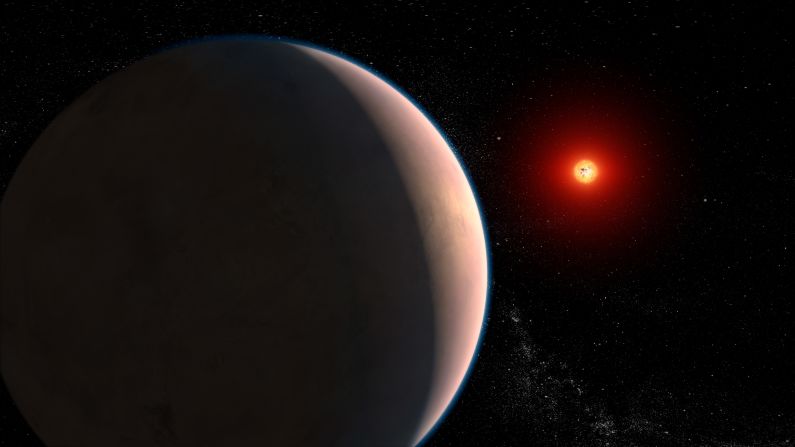

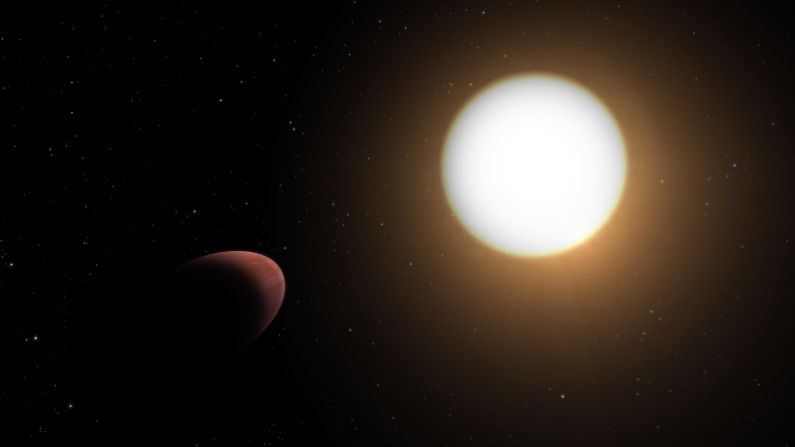

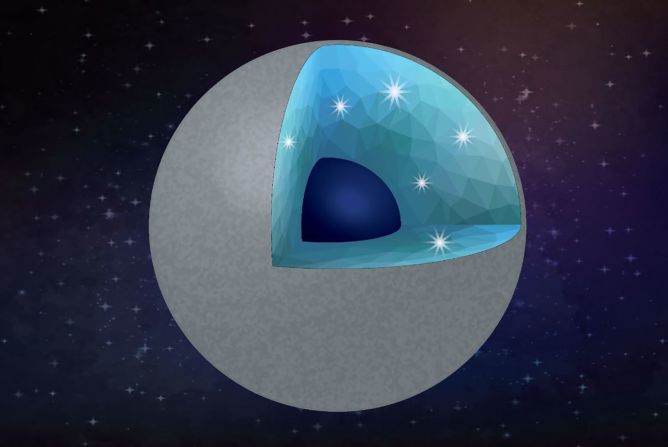

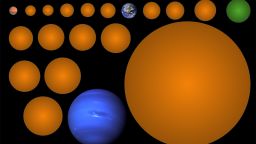

This type of exoplanet is the lowest density ever found outside of our solar system, which gives them their airy appearance when seen through a telescope. But despite that low mass they’re also incredibly large – and totally unlike any planet orbiting our sun.

We may truly understand them next year when the James Webb Space Telescope launches and has the ability to study their atmospheres. But for now, astronomers are trying to understand how super-puffs are possible. And they think the answer may be that super-puffs aren’t so puffy.

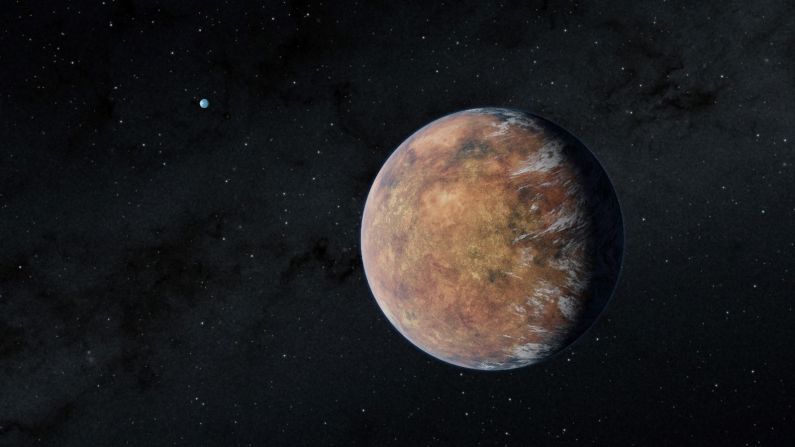

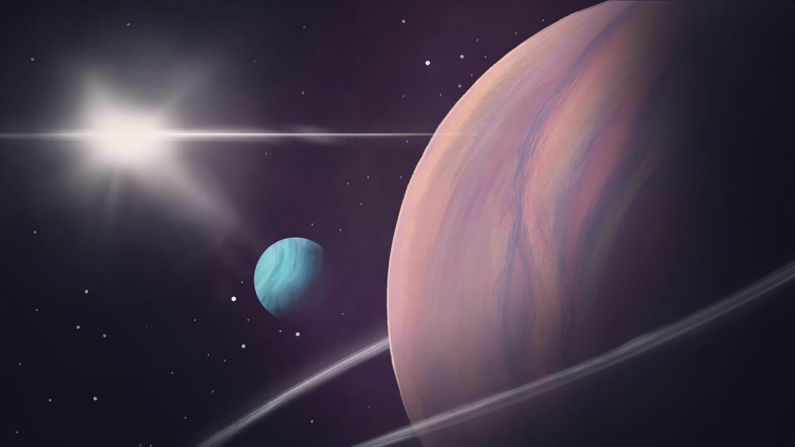

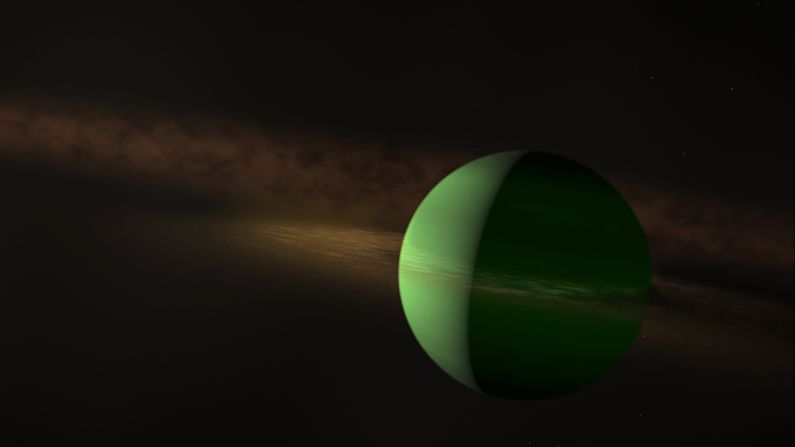

“We started thinking, what if these planets aren’t airy like cotton candy at all,” said Anthony Piro, study author and George Ellery Hale Distinguished Scholar in Theoretical Astrophysics at the Carnegie Institution for Science Observatories. “What if the super-puffs seem so large because they are actually surrounded by rings?”

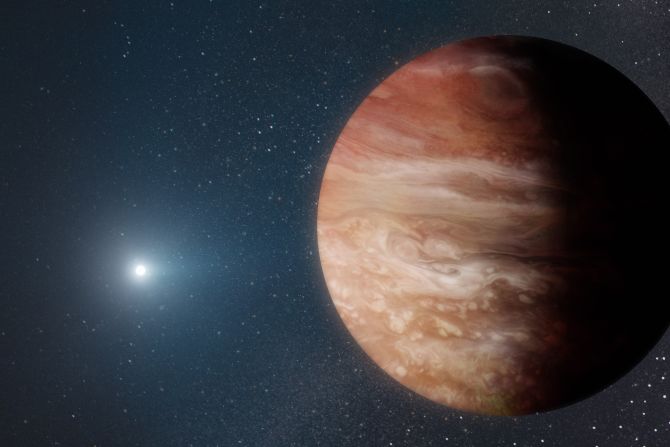

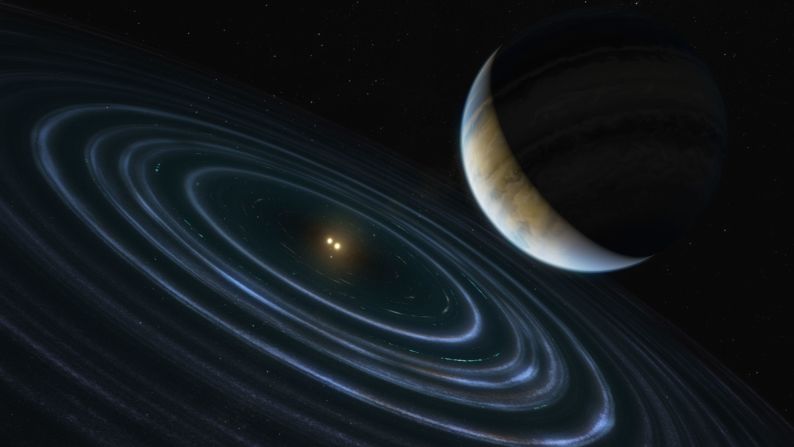

Rings around planets are common in our solar system, and are seen around Jupiter, Uranus, Neptune and most obviously, Saturn. It’s expected that they could be found around exoplanets, too, but rings are hard to spot at the distances between our solar system and others.

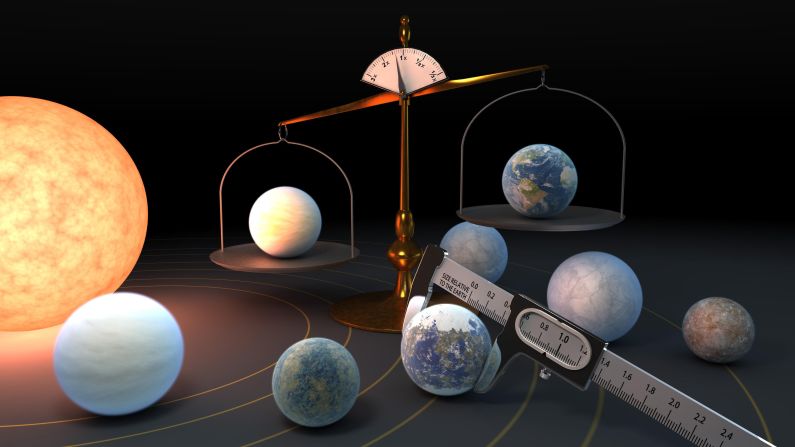

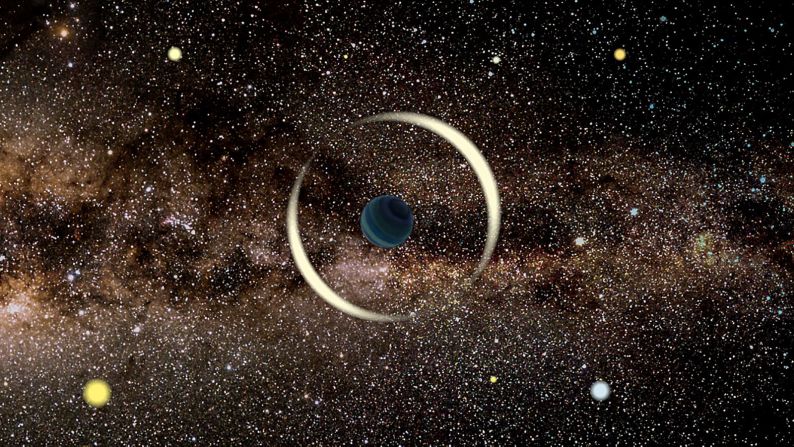

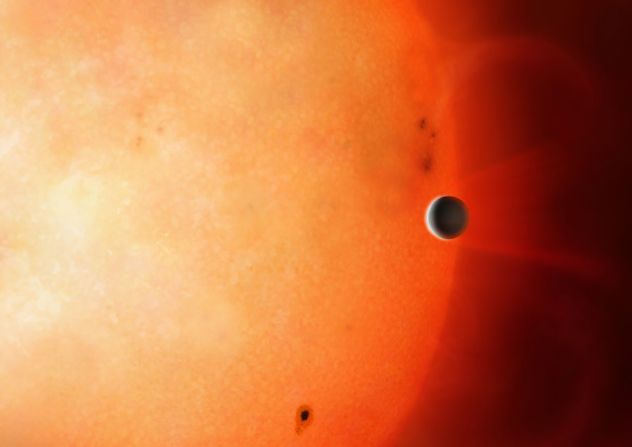

One method of finding exoplanets is called the transit method, tracking dips in starlight as planets orbit in front of their star. Larger dips correlate to larger exoplanets.

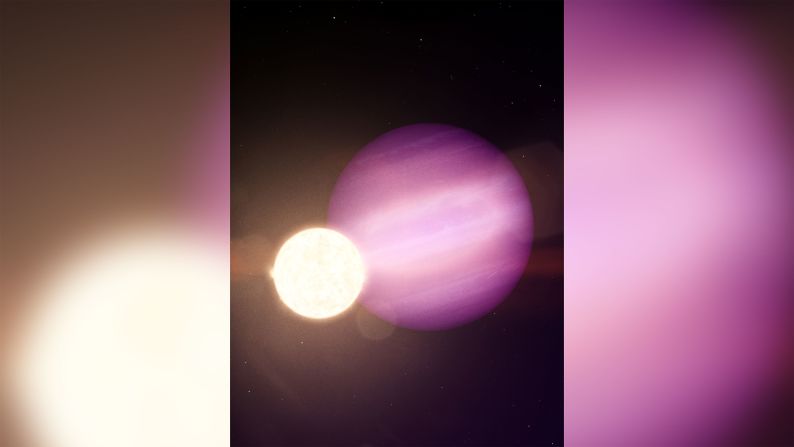

“We started to wonder, if you were to look back at [our solar system] from a distant world, would you recognize Saturn as a ringed planet, or would it appear to be a puffy planet to an alien astronomer?” asked Shreyas Vissapragada, study co-author, PD Soros Fellow and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow at the California Institute of Technology.

The two researchers simulated what a ringed exoplanet may look like through a telescope as they observed a transit, as well as the types of material that may comprise those rings.

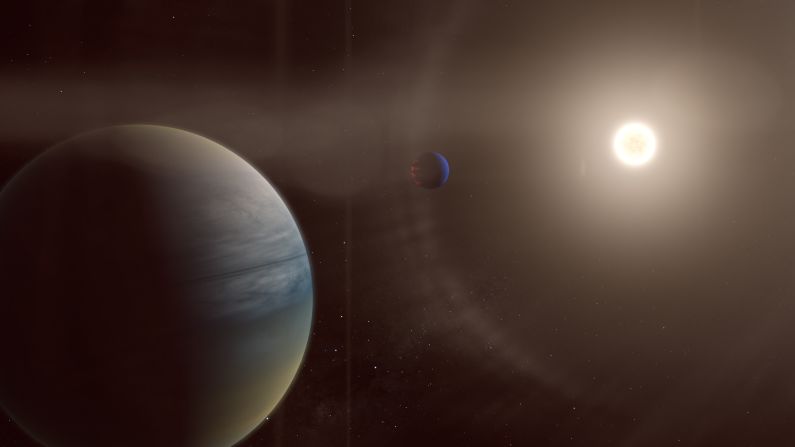

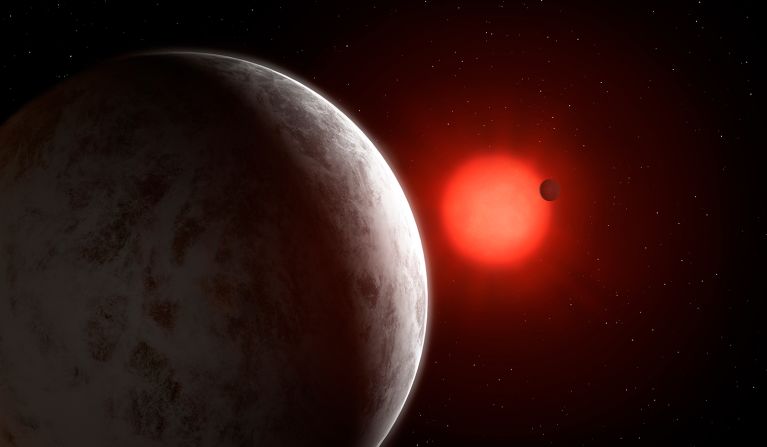

Ultimately, they found that rings could explain the size of some of the known super-puffs, via data collected during the nine-year, planet-hunting NASA Kepler mission – but not all of them.

The study published this week in the The Astronomical Journal.

They think that at least three known super-puffs could have rings: Kepler 87c, Kepler 177c and HIP 41378f.

“These planets tend to orbit in close proximity to their host stars, meaning that the rings would have to be rocky, rather than icy,” said Piro. “But rocky ring radii can only be so big, unless the rock is very porous, so not every super-puff would fit these constraints.”

Perhaps follow-up observations with the James Webb Space Telescope can reveal rings around other super-puffs, allowing for more understanding of these enigmatic cotton candy worlds.