Ever since a huge crater was discovered off Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula in the early 1990s, scientists have been confident that an asteroid slammed into Earth 66 million years ago and killed off the dinosaurs and most life on the planet.

But the cause has never been definitively settled, and some scientists have questioned the widely held “sudden-death by asteroid” theory. That camp believes that massive volcanic eruptions, which may have released climate-changing gases in the Spain-sized region known as the Deccan Traps, played a significant role.

Now, a group of researchers at Yale University are putting the blame back solely on the asteroid.

They say that any environmental impact from the eruptions and lava flows that occurred in the Deccan Traps (located in what is now India) happened well before the extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs, which scientists call K-Pg.

“A lot of people have speculated that volcanoes mattered to K-Pg, and we’re saying, ‘no, they didn’t,” said Pincelli Hull, an assistant professor of geology and geophysics at Yale and lead author of the study, which published Thursday in Science.

“What our study does is take 40 years of research and adds a bunch of new research. It combines this in the most quantitative tests you can do and it really doesn’t look like it (was the volcanoes).”

Some researchers believe that emissions from the volcanoes, which released gases like sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide, weakened the ecosystem so that dinosaurs went extinct more easily when the asteroid hit.

The Yale-led study investigated the timing of this outgassing by modeling the effects of carbon dioxide and sulfur emissions on global temperatures and comparing them with paleotemperature records spanning the extinction.

They found that at least 50% or more of the major outgassing from the Deccan Traps occurred well before the asteroid impact, and only the impact coincided with the mass extinction event.

The volcanoes did “cause a warming event,” but its effect had gone by the time extinction happened, said Michael Henehan, a former researcher at Yale who is now based at the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences.

“Volcanic activity in the late Cretaceous [period]caused a gradual global warming event of about two degrees, but not mass extinction,” said Henehan, who compiled the paleotemperature records spanning the extinction event.

To ascertain changes in temperature back then, Henehan used proxy records based on several sources, including chemical traces in fossils and other biomarkers.

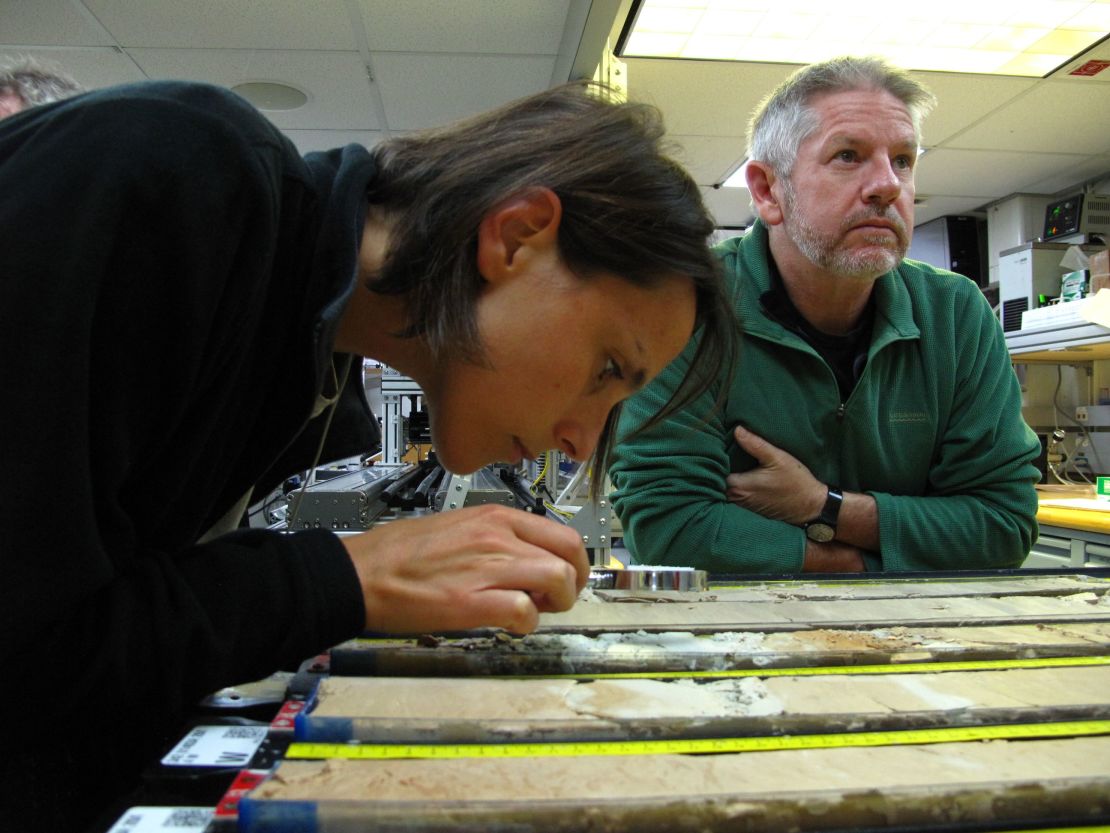

The researchers also examined cores of rock drawn from the sea floor, which showed when the asteroid hit.

“You can see impact — melted fragments of rock. It’s really, really clear on these cores of rock,” said Henehan.

So does this put the debate over what wiped out the dinosaurs to rest?

It should, says Hull.

“If someone came up with compelling evidence tomorrow, I’d be prepared to say we are wrong. But it really doesn’t look like it based on what we know today,” she said.