Researchers have launched a new study which hopes to better understand the link between playing soccer and developing dementia.

The project by the University of East Anglia (UEA) hopes to serially test former professionals, both male and female, every six months in order to map their rate of decline.

By using cutting edge technology, the project aims to detect signs of dementia long before noticeable symptoms, such as memory loss.

The new initiative follows a landmark study released by the University of Glasgow that revealed former players were around a three and a half times more likely to die from neurodegenerative disease.

“In former professionals, there is a problem. We now need to investigate that much further,” lead researcher of the UEA project Dr. Michael Grey told CNN Sport.

“What we’re interested in doing is looking at people who are actually still with us. I want to to follow them for years, ideally for the rest of their lives.”

The majority of participants will be able to take part in the tests from the comfort of their own homes, using their tablet or computer devices to complete simple tasks.

The project will include a number of “novel” techniques including testing spatial navigation, an area of cognitive function that Dr. Grey says seems to degrade more rapidly than others.

“I think the easiest way to explain it is if you drove into work today, you could probably close your eyes and point to your car, and you’d be pretty close to being accurate,” he said.

“People with dementia have challenges doing those types of exercises because it relies on an area of the brain that’s responsible for remembering where we are in space.”

The UEA wants to raise £1 million ($1.32m) for new study and hopes 10% of that figure will be crowd funded.

READ: ‘Hopefully no one has to die’: Taylor Twellman’s fears over head injuries

‘It does make you think’

Despite concussions being a dangerous consequence of the game, Dr. Grey says repetitive head trauma, such as heading the football, is a bigger issue in terms of degeneration.

There are concerns that the entire action of competing in the air, including accidentally clashing heads or falling awkwardly, can contribute to the problem.

Dr. Grey also says the theory of modern, lighter balls being less dangerous than the heavy balls of the past is a red herring, explaining the velocity of the ball has increased over time which could cause further damage.

“Each time we head the ball, there’s a little bit of micro damage to the neurons in the brain and doing that over and over again in a professional career is what we think is resulting in degeneration,” he said.

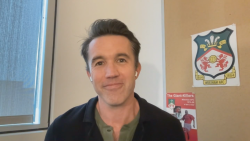

The project is now on the look-out for former professionals to take part, with former striker Iwan Roberts one of the first to register his interest.

The Welshman, who represented clubs such as Leicester and Norwich City, played over 700 times in his 20-year career and heavily relied on his heading ability to score countless goals.

The 51-year-old says he never thought about the possible dangers of his trade but is now keen to be involved in UEA’s long-term project.

“It does make you think,” Roberts, who retired in 2005, told CNN Sport.

“I’m not just talking about all the games that I played, I’m talking about repetitive heading on a daily basis to improve your heading ability, which as a big center forward I did every day at the end of a training session.

“I’d go with a coach and we’d have a left winger and the right winger and they just crossed balls for 45 minutes to an hour. I would just get into the habit of scoring goals with my head.”

‘People are not willing to talk’

Roberts, who has been filming a documentary about dementia and soccer for Welsh language channel S4C, says people within the game are now more aware of the dangers but still believes the sport’s governing bodies can do more in supporting ex-professionals.

“It’s something that people are not willing to talk about because certain authorities in this country [England] don’t want to be blamed for certain things,” he said.

The English Football Association (FA) and the Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) both helped fund the University of Glasgow field study which published its findings in October.

The FA responded by reissuing its best practices for concussion protocols and for coaching heading, saying “there is no evidence to show that heading can cause long-term damage.”

On its website, the PFA says neurological problems “have been on our agenda for the last 20 years” and have set up a dementia support document and helpline.

Dr. Grey believes the sport is finally getting to grips with the potential problem and hopes such organizations will continue to develop its understanding of such issues.

“I think the fact that we’re having this conversation is a good thing,” he said.

“It’s a cultural change that we need to effect. It will take some time, but we’ll get them on board.”

Researchers are looking for former professional players aged over 50 to take part in the study, in addition to active non-footballers aged over 50.