Whoever wins this week’s UK election, there’s more at stake for businesses and investors than at any time since the 1970s — and it’s not all about Brexit.

The future of Britain’s plan to leave the European Union, which would reverse 46 years of trade and economic integration, could be decided on Thursday. Huge domestic policy change also looms large.

Britain’s two main political parties both want to increase government spending after a decade of painful austerity under Conservative-led administrations. But opposition Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn has pledged to dramatically expand the role of the state and boost public spending to levels not seen in a generation if voters send him to Downing Street on December 12.

On Labour’s policy wish list: nationalizing major utilities, a32-hour work week, giving 10% of shares in large companies to workers, increasing the power of unions, freezing the retirement age at 66 and building out public housing stock on a large scale. The party has pledged to finance higher spending with big tax hikes for corporations and Britain’s wealthiest 5%. Borrowing to fund investment would reach £55 billion ($72.4 billion) annually by fiscal year 2023.

The overhaul would unfold at breakneck pace. Labour said Monday that it would begin the process of nationalizing water and energy companies within 100 days of taking office.

“It’s clearly a blueprint for a long term, fundamental change of the role, size, scale and scope of the state in the UK,” Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, an independent research institute, said at a recent presentation to journalists.

Proposed changes to taxes, spending and regulation would put Britain in line with many of its Western European neighbors. But such changes would look “very different from anything we’ve experienced in the UK, certainly since the 1970s,” Johnson said. Denis MacShane, a former Labour politician who served as Minister of Europe under former Prime Minister Tony Blair, called Labour’s ideas “the most left-wing proposals from a major party seen in a Western democracy since the ‘common program’ of 1970s France.”

A ‘simply huge’ shift

The United Kingdom already has universal health care and a substantial social safety net. But belt-tightening measures imposed following the global financial crisis have eaten away at budgets for policing, hospitals and welfare. Corbyn, who would be the first Labour leader since 2010, has promised to “rewrite the rules of the economy” if voters choose him over Conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Labour has proposed to increase day-to-day spending — a category that includes pay hikes for public sector workers, abolishing university tuition fees and rolling out free prescriptions — by £83 billion ($109.2 billion) in fiscal year 2023. Investment in long-term projects, such as a green infrastructure program and building new hospitals and schools, would double from current levels.

As a result, state spending as a share of national income would jump to a threshold not seen outside of the financial crisis since 1977, according to the IFS. The research group noted that this proportion of spending has never been sustained in theUnited Kingdom “for any significant period of time.”

“This is a simply huge increase that takes us to a big state by historical standards,” Torsten Bell of the Resolution Foundation, a think tank, wrote in his own analysis.

The size of the state would also grow through the nationalization of key utilities, including water, mail, energy infrastructureand railways. Corbyn recently announced that Labour would also provide “fast and free” broadband across the country by nationalizing Openreach, BT Group’s telecoms infrastructure arm. Taken together, the plans would shift 5% of total UK assets from private to public ownership, according to IFS.

To finance a wave of fresh spending, Labour will need to lean on higher taxes and borrowing while interest rates are near record lows. The tax companies pay on their profits would jump to 26% from 19%, raising more as a percentage of GDP than any other G7 country, per the IFS. The party has also pledged to tax financial transactions and reform how the government taxes capital gains and dividends. And it would increase income taxes on people making more than £80,000 ($105,275) per year.

Even so, IFS economists said they doubt that Labour can bring in as much tax revenue as promised over the long term, especially if the party’s policies harm business confidence. They also warn that certain tax and spending pledges were not covered in Labour’s funding plan.

Why business is worried

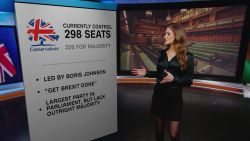

Corbyn is trailing Johnson in the polls, but the memory of the 2017 general election — when Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May, who expected a landslide win, lost her majority in parliament — means pundits are reluctant to write him off entirely. Plus, many elements of the Labour platformare popular with voters.

“People like a lot of this stuff in theory, a lot more than I think the Conservatives themselves realize,” said Robert Ford, professor of political science at the University of Manchester. Many voter concerns, he said, center on “cost and competence.”

The prospect of Corbyn as UK leader, even through a coalition government with another party, has business feeling anxious.

While investors and executives like the fact that Labour wants a second referendum on Brexit with an option to remain in the European Union — seen by most analysts as the least damaging option economically —and manysupport greater stimulus spending, there is visceral opposition to what else is on the menu.

“Labour’s default instinct for state control will drag our economy down, rather than lift people up,” Carolyn Fairbairn, director general of the Confederation of British Industry, a lobby group, said in a statement when Labour published its manifesto.

Some of this aversion could be tied to Labour’s push for large scale structural change. But there are also elements of the party’s platform that could directly eat into corporate profits.

Labour has proposed to hike the country’s minimum wage to £10 ($13.15) an hour, an especially large increase for younger workers. It’s also pledged to expand collective bargaining by sector across the economy, increasing the number of Britons whose pay would be negotiated in talks between unions and management. Meanwhile, the party would mandate that one-third of board seats are reserved for worker representatives who would have a say on executive compensation.

Garnering significant attention in the business community are two of Labour’s bolder proposals: the pledge to achieve an average 32-hour workweek within a decade, and a promise to give corporate shares to workers.

Though details about the latter remain hazy, Labour has said it would require large companies to set up “Inclusive Ownership Funds,” allowing for up to 10% of the company to be controlled by employees, who would receive dividend payments.

Alfie Stirling, head of economics at the New Economics Foundation, a think tank, called this approach “potentially transformative” since it gives workers more clout. “It changes the power dynamic of a workplace,” he said.

Collectively, Labour’s policies have a distinct anti-business feel, according to Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at Capital Economics. The expectation is that they “would negatively impact business confidence and business investment,” she continued. Investors would likely react to a Corbyn election win by dumping the pound and selling shares in UK companies.(The pound has shot up in recent days to a seven-month high against the dollar as markets bet on a Johnson win.)

Then there’s the concern that Labour, once in power, could go even further than what’s in its manifesto. The worry, per Gregory: If a significant policy like nationalizing broadband was added to the party manifesto at the last minute, what else could be on the table?