(CNN)NASA's stationary InSight lander is slowly but surely getting to know Mars on a deeper level.

Since landing on Mars in November 2018, InSight has been taking selfies, providing daily Martian weather reports, detecting quakes on Mars and hearing strange sounds. But its heat probe experiment was struggling to burrow beneath the surface of the red planet.

Now, it's making progress again. Over the past week, its heat probe has dug three quarters of an inch.

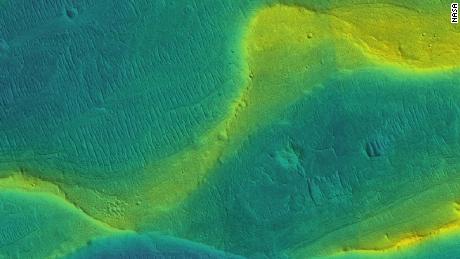

While the Curiosity rover is currently exploring Gale Crater, InSight is a stationary probe permanently parked in Elysium Planitia. It's along the Martian equator, bright and warm enough to power the lander's solar array year-round.

InSight, or Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport, is a two-year mission to explore a part of Mars that we know the least about: its deep interior.

The suite of geophysical instruments on InSight sounds like a doctor's bag, giving Mars its first "checkup" since the planet formed. Together, those instruments take measurements of Mars' vital signs, such as its pulse, temperature and reflexes -- which translate to internal activity like seismology and the planet's wobble as the sun and its moons tug on Mars.

But "the mole," or the self-hammering heat probe, had only dug roughly 14 inches into the surface since February 28. It was designed to reach at least 16 feet beneath the surface to record how heat escapes from the interior, according to NASA.

The mole seemed to be missing a key factor in digging: friction in the surrounding soil. Instead, the team believes that the probe was simply bouncing in place. Applying extra pressure helped.

Pinning, or pressing the scoop on the robotic arm, is providing that friction so it can keep digging.

"Seeing the mole's progress seems to indicate that there's no rock blocking our path," said Tilman Spohn, principal investigator of the instrument. "That's great news! We're rooting for our mole to keep going."

Relocating the mole isn't the solution because it wasn't designed to be moved once it began digging.

The mole, known as the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package, was provided by the German Aerospace Center. In June, the experiment's team used the spacecraft's robotic arm to remove a structure keeping the mole steady so they could get a more direct view of what happened when the mole tried to dig.

A camera on the arm revealed between two and four inches of duricrust beneath the surface. Duricrust is a hard crust at or near the surface of the ground typically formed by the accumulation of upward migration and evaporation of ground water.

This soil that seems cemented together is thicker than what the mole was designed for. And it's nothing like the soil that previous Mars missions have run into before.

"The mole still has a way to go, but we're all thrilled to see it digging again," said Troy Hudson, an engineer and scientist who has led the mole recovery effort at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "When we first encountered this problem, it was crushing. But I thought, 'Maybe there's a chance; let's keep pressing on.' And right now, I'm feeling giddy."