Space is not a friendly environment, even for the stars, planets and galaxies born in its cold, violent reaches. But solar systems have found a way to keep their newborn planets from accidentally getting too close to their host stars, according to a new study.

Without a physical “baby-proofing” structure in place, planets born in the inner regions of a star system might drift and dive right into their host star.

And during NASA’s Kepler mission, numerous super-Earths, or planets with a mass higher than Earth’s, were found in close orbits around their stars, toeing the line of so-called “baby-proof” region.

Researchers published their findings about this process in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics on Thursday.

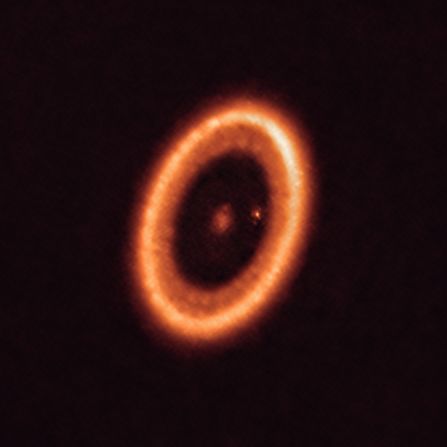

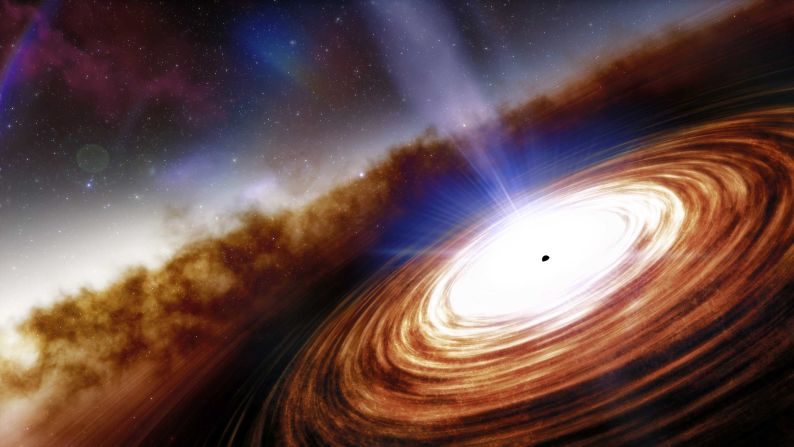

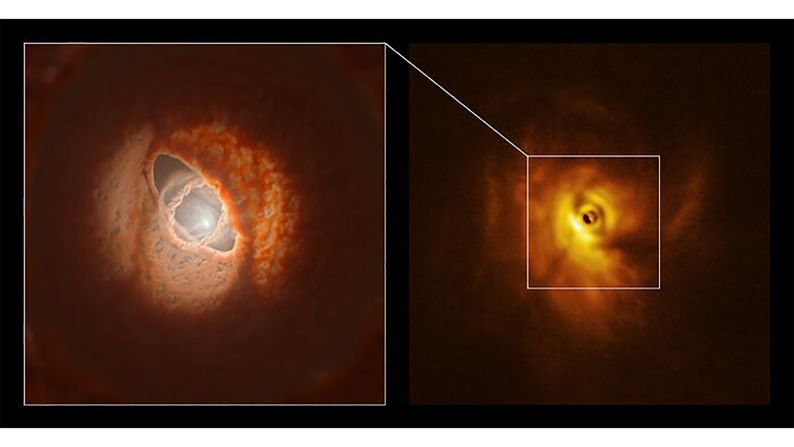

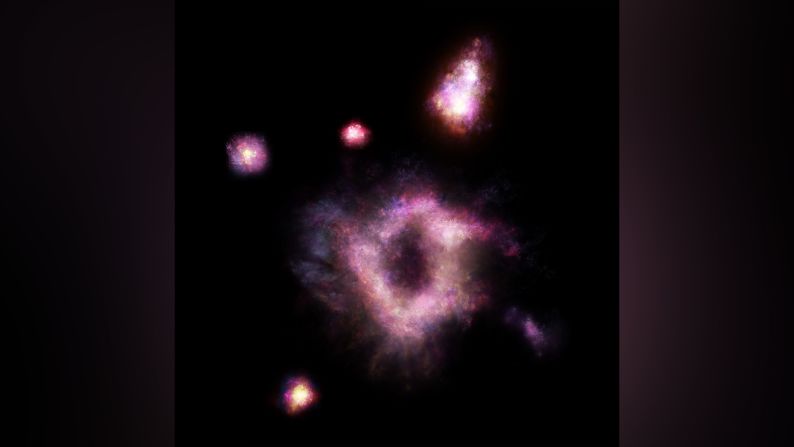

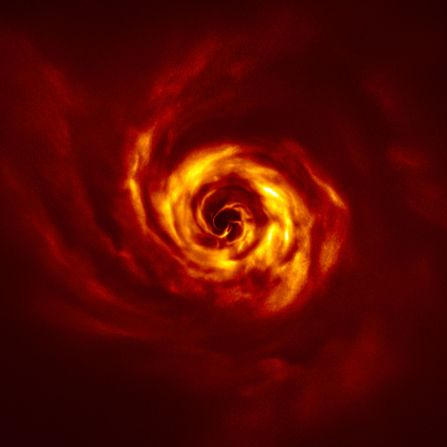

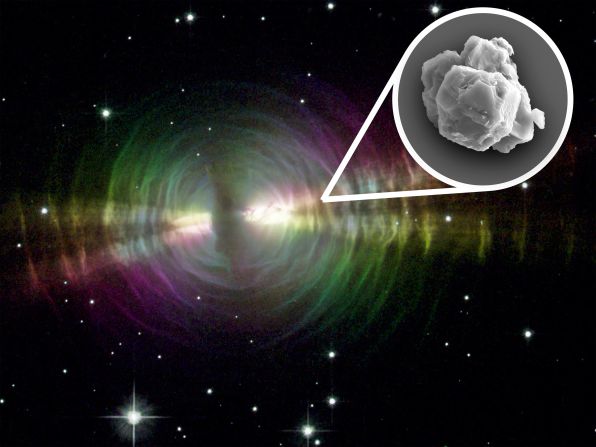

The current understanding for planet formation follows a specific order. Stars form from clouds of collapsing gas and dust. Then, a protoplanetary disk of leftover gas and dust surrounds the star. Planets form from this disk, using the leftover gas and dust that created the star to pull together solid material for planets.

This can take place over the course of a few million years as the planets grow from dust rains to round objects with a solid core.

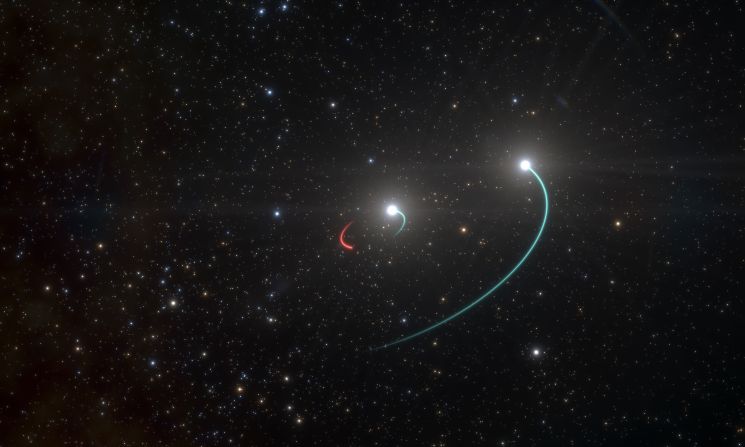

New planets, like babies, are kind of wobbly. They don’t establish a stable orbit around the star right away, but move in and out of range. Much like new parents establishing boundaries in their home to keep their toddler safe from potential dangers, these new planets need something to stop them from wobbling too close to their star.

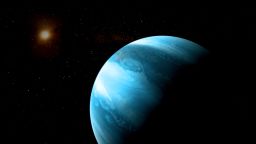

The researchers wanted to understand what kept the new planets in line, as well as the mechanism that allowed for super-Earths to orbit so closely to their host star that they zipped around the star once every 10 to 12 Earth days.

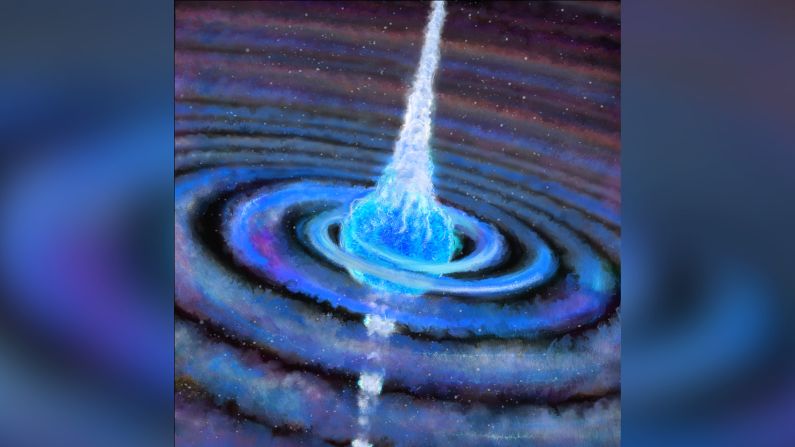

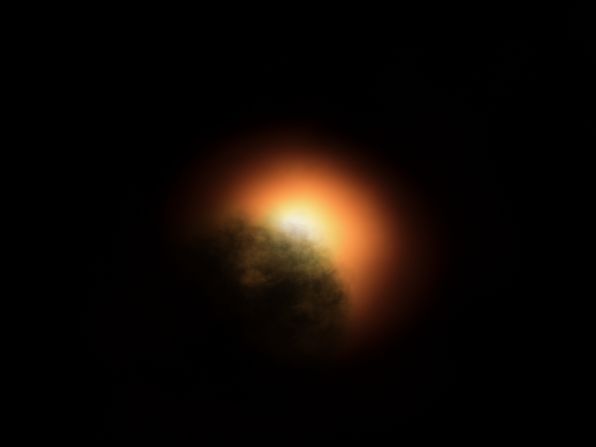

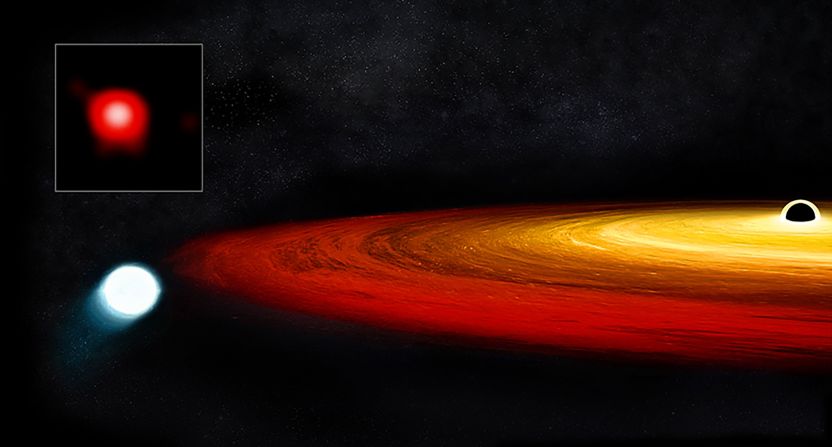

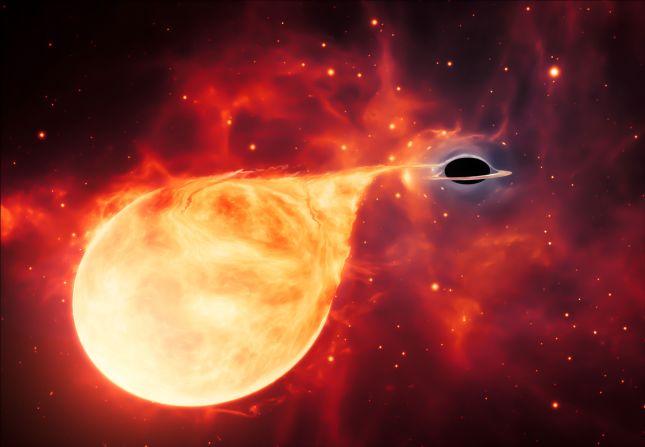

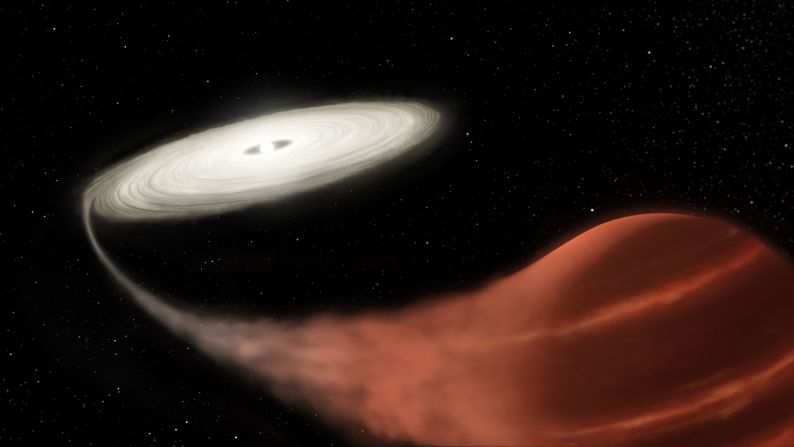

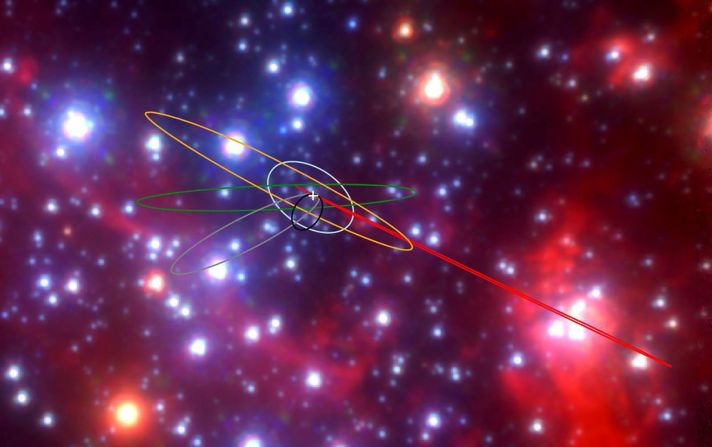

Stars throw off immense radiation. The protoplanetary disk around them contains a boundary called the silicate sublimation front, where temperatures exceed 1200 Kelvin and dust particles like silicates turn into extremely hot, turbulent gas.

A rocky planet close to the star, like a super-Earth, will travel through that gas and has a gas trail of its own because it’s still forming. When the planet hits the boundary, the thinner, hot gas from the star interacts with the denser gas of the planet, resulting in a kick that bounces the planet away.

“Why are there so many super-Earths in close orbit, as Kepler has shown us? Because young planetary systems have a built-in baby-proof barrier,” said Mario Flock, study author and postdoctoral scholar at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

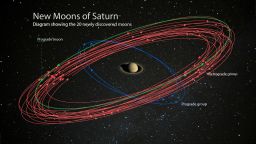

The researchers said that there is another option, which they tested by tracing the movement of much smaller objects the size of pebbles. The thin, hot gas of the star rotates quickly and when small objects try to essentially keep up with this quick orbit, they get tossed off like a child from a ride that’s too fast.

When applied to our own solar system, these theories point to the suggestion of a rocky planet closer to our sun than Mercury. Did the planet just not form or was it kicked out of the solar system? The researchers believe this idea could prove intriguing for further study in the future.

Pondering the idea, Flock said it’s interesting to think “not only that our Solar System was baby-proof – it is possible that the baby thus protected has since ‘flown the nest.’”