Driver's ed for robotaxis: A grueling exam looms for self-driving cars

Updated 1504 GMT (2304 HKT) October 4, 2019

Washington, DC (CNN Business)Self-driving cars are coming. Or so we're told. But they still face an existential question: When is a self-driving car truly ready to drive on its own?

That will ultimately be judged by regulators such as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. But to prep for that ruling, automakers and tech companies are putting cars on roads and, perhaps more importantly, in simulated environments to fine-tune reactions to events seldom found in the real world.

A 16-year-old human can be tested on streets and highways near their hometown, and then be entrusted to drive nationwide. But a robotaxi's abilities don't generalize the same, requiring a more exhaustive test of scenarios specific to a city and even an intersection.

Most Americans already aren't comfortable with the idea of riding in a self-driving car. For the self-driving industry to earn the trust of the public and regulators, they'll need to ace the test. An industry projected to be worth $7 trillion is on the line. The tech and auto industries are counting on simulated tests done on computers to prove the cars are safe enough to entrust with our lives and those of our loved ones.

CNN Business spoke with simulation experts at 10 companies including automakers, big tech companies and startups that are entirely focused on simulation. They're spending millions to answer a big question: What should be on the test?

No simulation, no self-driving cars

Cruise, GM's self-driving team, runs 200,000 hours of simulated tests every day. Waymo, the self-driving arm of Google's parent company, has simulated more than 10 billion miles of driving.

Self-driving companies are embracing simulation testing because it's affordable, time-efficient and safe. The risk of on-road tests surfaced last year when an Uber test vehicle killed a pedestrian. Simulations allow companies to test situations that you wouldn't want to put a self-driving car in -- like a child running into its path from behind a parked car -- but nevertheless need to.

Zoox had a problem it wanted to solve. The Silicon Valley startup wanted its self-driving cars to better handle yellow left-turn signals, a rarity during on-road testing. So a team of artists made artificial examples of yellow left-turn signals, and loaded them into its simulated environments. Soon Zoox's software was better at recognizing left-turn signals in the real world, according to co-founder Jesse Levinson.

Lyft (LYFT) noticed earlier this year that its cars were slamming on the brakes when they were cut off by other cars. Engineers recreated the scenario of being cut-off in simulation. According to Luc Vincent, who leads autonomous driving efforts at Lyft, they were able to more quickly and cheaply tweak the software to soften the harsh braking.

Aurora, a self-driving startup that Amazon, Hyundai and Kia have invested in, does the bulk of its testing in simulation. When its cars drive on actual roads, they're generally being manually driven, so Aurora can later compare how its self-driving software varies from human drivers.

"We tell our drivers, look we just want you to drive like an expert human," Aurora co-founder Sterling Anderson told CNN Business.

Simulation 101

The engineers who write new software for self-driving vehicles can run simulated tests from their desks to see if their software improves a car's driving, at least in the simulated environment. Some companies run regularly simulated tests every hour, and overnight. Improving how the car handles one task ŌĆö like right turns on red ŌĆö risks disrupting something else.

"It's a bit like a whack-a-mole. You solve one problem, another might emerge," said Applied Intuition CEO Qasar Younis, whose Sunnyvale, California-based startup has raised more than $50 million to build simulation tools for self-driving cars.

A single intersection can have tens of thousands of scenarios, according to Younis. Factors include the weather, the car's tire pressure, potholes, how many people are in the car, what pedestrians are doing and how assertive the car is.

The world is complex and random, and vehicles need to be able to handle rare situations, like seeing a traffic light that's swinging in the wind at sundown.

"The list is almost infinite," said Lyft's Vincent.

Applied Intuition and Aurora have used federal government crash reports to help them understand situations to test. Aptiv, the auto supply company, puts its vehicles through 40,000 scenarios. Most companies declined to say how many scenarios they're testing, but acknowledged they're adding new circumstances as they learn.

"You never get to perfect," said Mike Wagner, CEO of Edge Case Research, a Pennsylvania company devoted to making automated systems safe. "The goal is to be ethical as you're going from where we are today to where we want to be."

Simulation's shortcomings

Tesla CEO Elon Musk, whose company uses simulation, has been critical of the tool, saying it's comparable to grading one's own homework.

"You don't know what you don't know," Musk cautioned at Tesla's autonomy day earlier this year. "The world is very weird and has millions of [unusual] cases."

Bryan Reimer, research scientist in the MIT AgeLab and the associate director of the New England University Transportation Center at MIT, has called for public-private partnerships in self-driving vehicles, to make sure the private sector makes the right decisions on questions like what scenarios to test.

"It's really, really difficult to make the test for [a self-driving vehicle] right now," Reimer said. "Only the private sector will actually develop the data needed to know some of these answers. And we cannot allow this to end up in another Boeing-like situation," referring to two crashes of the 737 Max, which arose from faulty autopilot software that was lightly regulated.

The self-driving industry is so young that best practices haven't been established for simulation. Many companies have made hires from fields with a history of simulation, such as aeronautics.

Many people cautioned that not all simulators for self-driving cars are created equal.

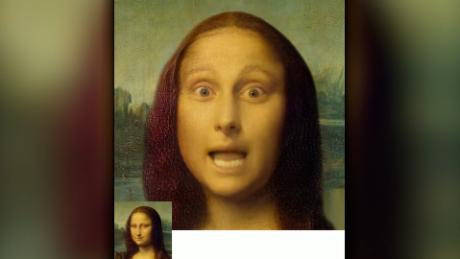

A simulator might look like a high-definition video game, but that's not necessarily enough. It needs to have accurate physics and results that won't vary depending on when the test is run. One unsolved challenge is making sure the simulated humans ŌĆö drivers, pedestrians and cyclists ŌĆö act realistically.

Waymo uses data from the millions of miles it has driven on roads to train an artificial intelligence system to imitate actual drivers and pedestrians. It tests factors like how often the simulated human drivers and pedestrian crash into each, to help determine if they're realistic or not.

"It's a budding field," said Drago Anguelov, Waymo's principal scientist. "If you look at a lot of the simulated worlds it creates a lot of not-so-realistic worlds which ultimately don't test the thing you should be testing."

Uber, for example, recently was testing how its cars handled a scenario in which a pedestrian stands behind a parked car along a road. The simulated cars weren't slowing for the pedestrian as much as its real-world cars. An Uber team devoted to confirming simulation's accuracy found that the simulator was telling the simulated car the color of the traffic lights ahead. With green lights coming up, the car was more confident driving faster.

So Uber tweaked its simulator to make sure the cars wouldn't know the color of traffic lights ahead, unless they were so close they'd be seen in the real world. Then the simulated and real-world cars started behaving identically.

One challenge was solved, but more are sure to arise.

"This is a generational type technological challenge," said Hugh Reynolds, who leads simulation at Uber.