Chief Justice John Roberts faces unprecedented national turmoil as he begins his 15th year presiding over America’s highest court.

An impeachment inquiry is underway for Donald Trump, a president who, beyond the grievances driving the US House of Representatives, pounds away at the judiciary as if it were an extension of the political branches – something Roberts and other justices strongly deny.

Dueling sets of US senators have filed documents questioning the court’s independence. Other lawmakers running for president have called (in vain, no doubt) for the impeachment of newest justice, Brett Kavanaugh. The drumbeat for “court packing,” the addition of justices beyond the current nine to change the ideological makeup of the bench, is stronger than it has been in decades.

And all this has nothing to do with the difficult cases – from LBGT rights to immigration to gun control to abortion – on the calendar for the new 2019-20 session, all in the middle of a presidential election year.

Roberts is both exactly where he wants to be – at the fulcrum of the law – but also where he does not want to sit, at the center of the political world.

RELATED: Exclusive: How John Roberts killed the census citizenship question

The new abortion access case from Louisiana could pose the thorniest challenge. Ever since centrist-conservative Justice Anthony Kennedy retired in 2018, an overriding question has been whether the Roberts Court would reverse Roe v. Wade. The Louisiana dispute does not directly test the 1973 milestone Roe, which made abortion legal nationwide. But the dispute would affect women’s access to abortion clinics, particularly outside urban centers.

When Roberts was asked last month about public criticism of the court, including from Democratic senators who had submitted a brief in a Second Amendment case, the chief justice insisted such complaints do not influence the justices’ work.

“We will continue to decide cases according to the Constitution and laws without fear or favor,” he said.

At that New York appearance, the 64-year-old Roberts repeated the mantra he has voiced since he was appointed in 2005 by Republican President George W. Bush: The justices are not engaged in politics.

That message has become more urgent in the volatility of today’s Washington.

“When you live in a politically polarized environment,” Roberts said, “people tend to see everything in those terms.”

In recent days, Trump has reinforced the confluence of politics and the high court as he has defended Kavanaugh. At a Florida appearance on Thursday, Trump asserted that Kavanaugh’s critics wanted to intimidate him into shedding his usual conservatism.

“They’re trying to turn his vote liberal but he’s a much tougher guy than that, I hope,” Trump said.

Echoes of FDR era

Roberts’ refrain that the court is above politics carries more personal salience, as he is now positioned to cast decisive votes in many of the most important, incendiary cases.

Rarely has the chief justice of the United States, who sits at the center of the elevated mahogany bench, also been at the ideological middle of the nine. The closest comparison may be to Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, who presided during the Great Depression and as President Franklin D. Roosevelt was trying to solve the nation’s economic problems with his New Deal initiatives.

Hughes, who served first as an associate justice 1910-1916 and then as chief 1930-1941, also took the lead for the third branch to forestall FDR’s 1937 “court packing” plan.

As the court majority invalidated, at first, FDR’s economic legislation, the frustrated president proposed adding a new justice for every sitting justice older than 70. At the time, six of nine were over 70. (Congress has the authority to determine the size of the Supreme Court, which has been set at nine since 1869.)

Hughes navigated behind the scenes with Senate leaders to help thwart the “court packing” proposal, which had also failed to draw significant public support.

“It fell to Hughes to guide a very unpopular Supreme Court through that high noon showdown against America’s most popular president since George Washington,” Roberts, the nation’s 17th chief justice, recounted in a 2015 talk focused on Hughes, the nation’s 11th.

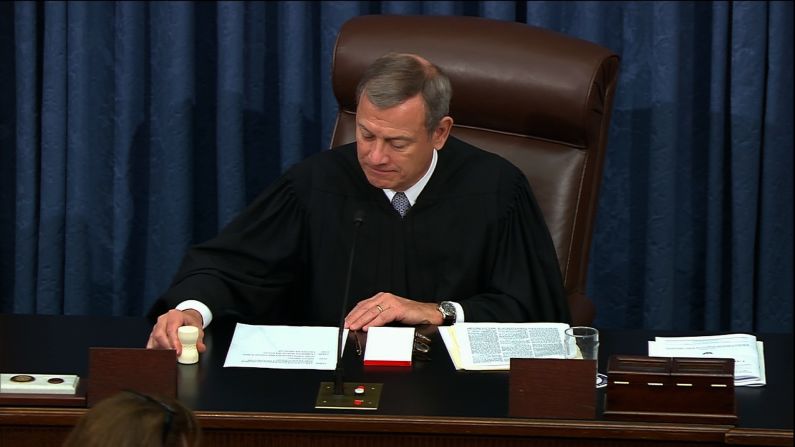

Beyond his responsibility for cases at the Supreme Court, Roberts may be poised to carry out a role that only two of his predecessors have had. Under the US Constitution, he would preside over a Senate trial if Trump were to be impeached in the US House of Representatives. In 1868, Salmon P. Chase oversaw the Senate trial of President Andrew Johnson, and in 1999 William Rehnquist presided over that of President Bill Clinton. (Both presidents were acquitted.)

Ideological shift on abortion

During the last session, Roberts edged at times to the left, perhaps to ensure that the court majority did not move dramatically rightward after Kennedy retired. Kennedy, a 1988 appointee of President Ronald Reagan, amassed a record that defied ready labels. He joined with liberal justices, for example, to protect gay rights and to preserve affirmative action in higher education.

The abortion rights dispute may further measure Roberts’ apparent effort to ensure he does not appear only in unison with fellow conservatives, all Republican appointees. (The four court liberals were appointed by Democratic presidents.)

Kennedy had been the crucial fifth vote, joining with those on the left, to uphold abortion rights, most recently in a 2016 Texas case.

Roberts dissented as Kennedy and the other justices in the majority struck down the Texas law that imposed tough standards on physicians and facilities, including a requirement that doctors who perform abortions have so-called “admitting privileges” at a local hospital. That law had led to the closure of multiple clinics in Texas.

The pending Louisiana case involves a similar “admitting privileges” mandate on physicians. The US Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit upheld the regulation with a cramped interpretation of the high court’s ruling in the Texas case. Last February, Roberts cast the fifth vote with liberal justices to block the Louisiana law from taking effect before the justices could review the merits of a challenge to it.

Roberts, in his nearly 15 years on the high court, has never voted to invalidate an abortion regulation, and the Louisiana dispute, June Medical Services v. Gee, could offer the first signs of any shift in the reproductive rights area on the post-Kennedy court.

A separate controversy on the justices’ new calendar, involving Trump’s immigration policy, could similarly reveal this new phase of Roberts’ tenure.

For years, lawyers liberally quoted the opinions of Kennedy, the erstwhile decisive vote. Now, it’s Roberts.

Attorneys on both sides are selectively citing Roberts’ past statements to bolster their arguments in the dispute over President Trump’s effort to end the Obama-era policy of delaying deportation of young, undocumented immigrants brought to the US as children.

The Justice Department, defending the Department of Homeland Security’s attempt to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, tells the justices their review must be narrow. Citing Roberts’ words from his June decision in the 2020 census controversy, the lawyers say the court “may not substitute its judgment for that of the agency.”

Roberts had said in the census case, Department of Commerce v. New York, that the administration has considerable latitude to add a question asking people about citizenship status but that, in this particular situation, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, had contrived his explanation for taking the step.

Lawyers representing immigrants and other challengers alternatively point to the chief’s statements demanding “reasoned” explanations for a policy change.

They insist that the Secretary of Homeland Security “suddenly announced a new policy,” failing to account for “enforcement resources or the significant costs to DACA recipients, their families, communities, workplaces, schools, and the larger economy.”

The DACA dispute is among those most likely to test Roberts’ notion that the five Republican justices and four Democratic justices do not divide along partisan lines in deciding cases.

That’s a “misperception,” Roberts said, declaring, “We don’t go about our work in a political manner.”

CNN’s Ariane de Vogue contributed to this report.