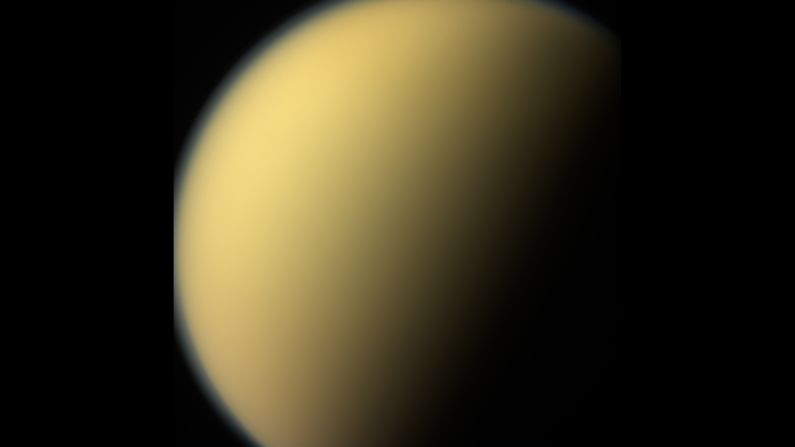

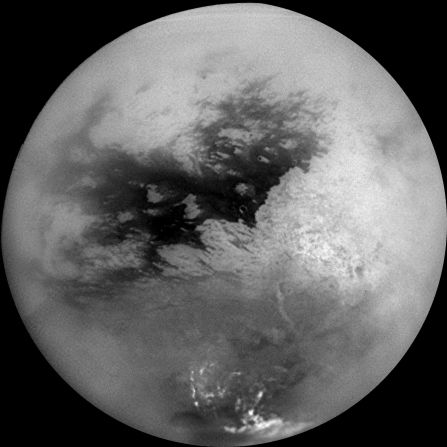

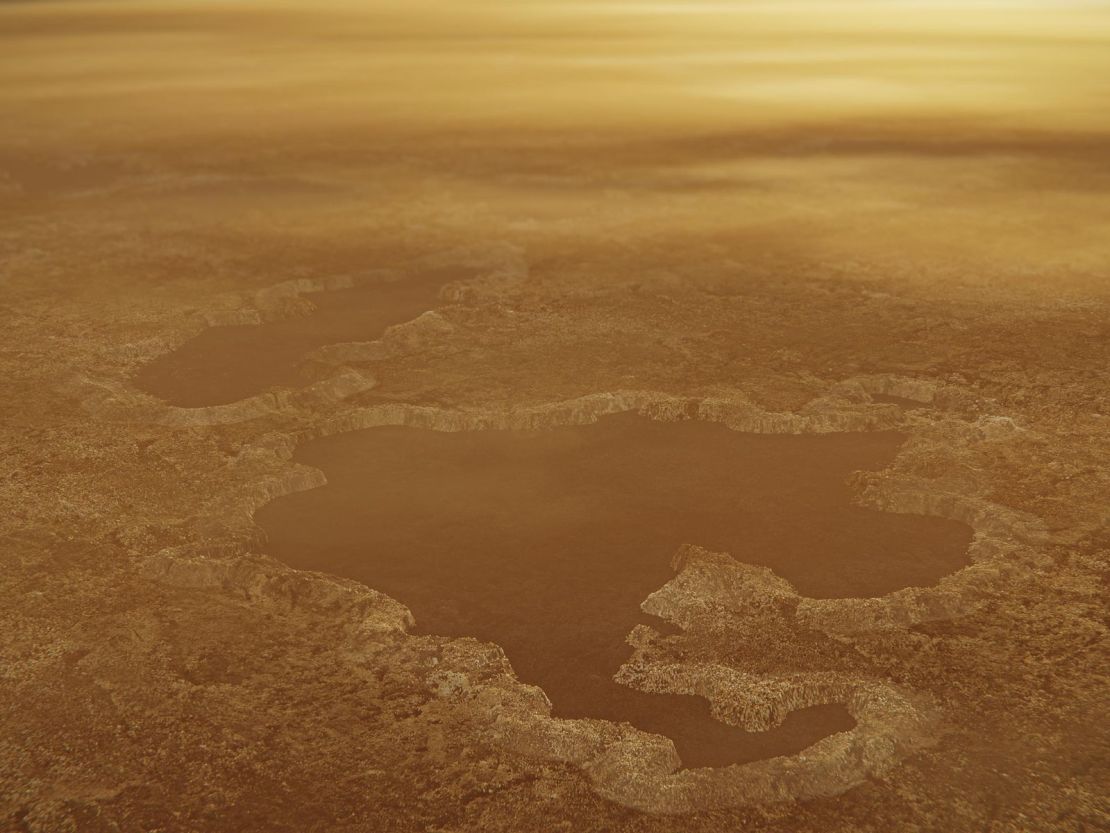

Saturn’s moon Titan is a curiosity in our solar system, the only other body besides Earth to host liquid water on its surface. And it’s the only moon in our solar system that has an atmosphere. But it’s not exactly inviting. The lakes on the icy moon are filled with liquid ethane and methane.

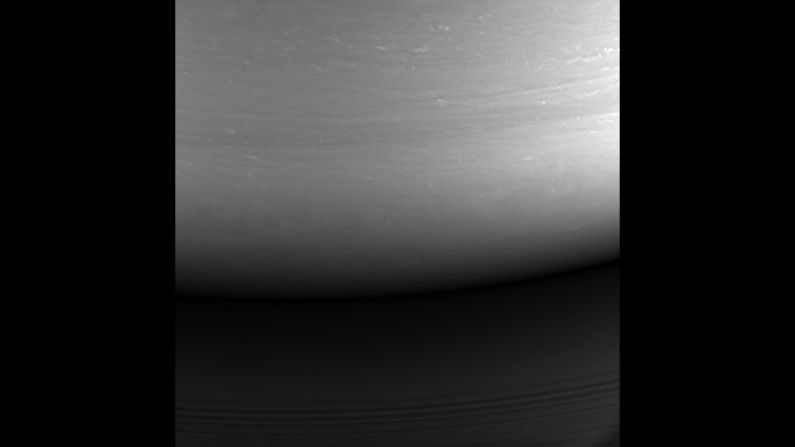

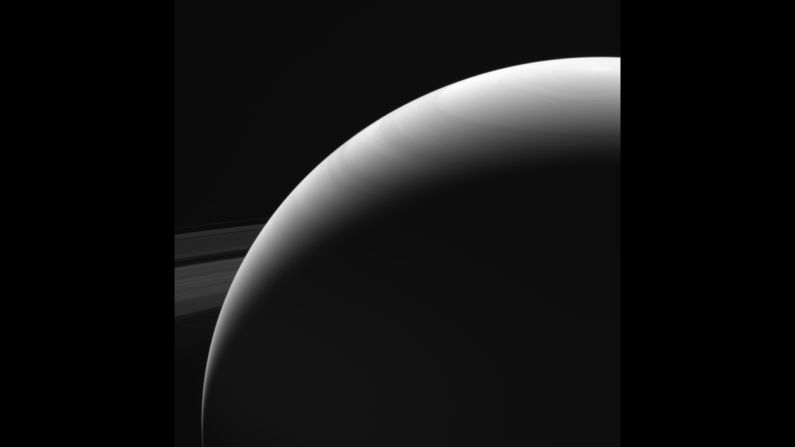

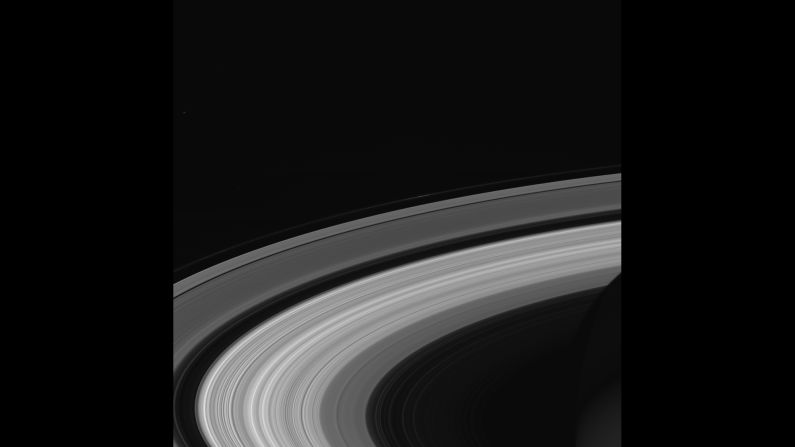

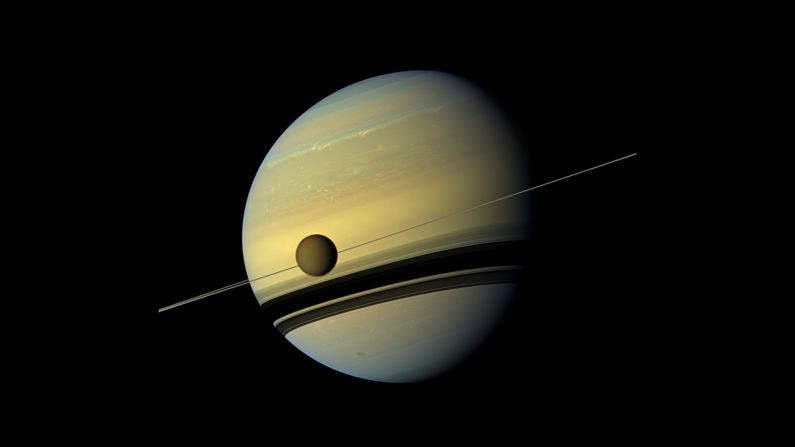

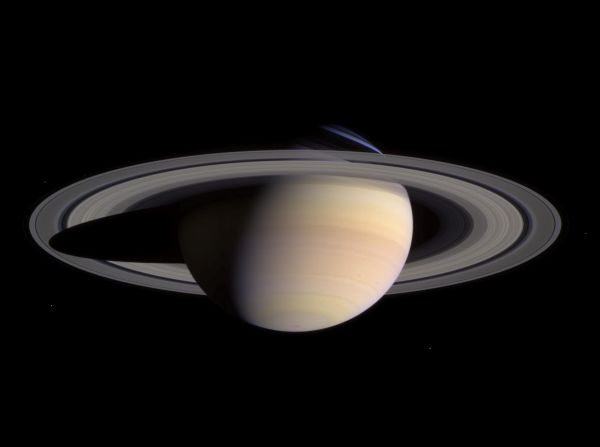

Titan was investigated by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft before its mission ended in 2017. A recent study of radar data gathered by Cassini as it observed Titan suggests how the lakes on Titan may have formed in the first place. The study published this week in the journal Nature Geosciences.

Some of the lakes on Titan are steeply rimmed, with the edges reaching heights of hundreds of feet.

Previously, researchers believed that the liquid methane created its own space on the surface by eroding ice and organic compound bedrock, allowing those areas to fill up. There’s an analog to this on Earth when water dissolves limestone. These form karstic lakes.

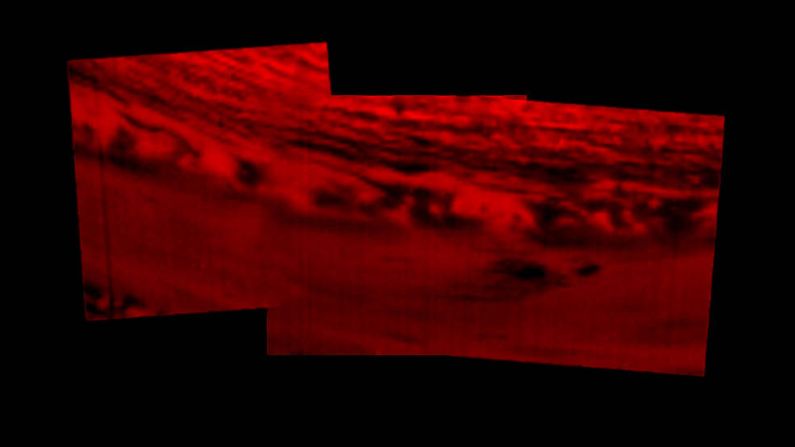

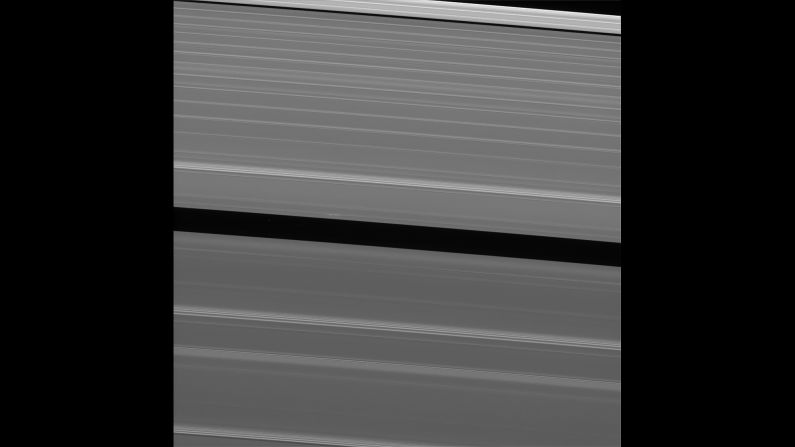

But images from the Cassini flyby didn’t match up with this model for the smaller lakes with steep rims on Titan’s surface that jet way beyond sea level.

Now, the researchers who studied these images propose that areas of liquid nitrogen within Titan’s crust became explosive when they warmed up, creating towering, steep rims around craters where liquid methane could reside.

“The rim goes up, and the karst process works in the opposite way,” said Giuseppe Mitri, research team leader at G. d’Annunzio University in Italy. “We were not finding any explanation that fit with a karstic lake basin. In reality, the morphology was more consistent with an explosion crater, where the rim is formed by the ejected material from the crater interior. It’s totally a different process.”

This model for the craters could actually help showcase different periods of warming and cooling on the moon. Although it’s about negative 290 degrees Fahrenheit, Titan has experienced different periods that help resupply its methane. The methane within Titan’s lakes is also in its atmosphere.

During times of cooling on Titan, nitrogen was likely the key element in the atmosphere, raining down onto the crust and collecting beneath it. Then, warming would cause the nitrogen to turn into expanding vapor to create a crater.

“These lakes with steep edges, ramparts and raised rims would be a signpost of periods in Titan’s history when there was liquid nitrogen on the surface and in the crust,” said Jonathan Lunine, study co-author and Cassini scientist.

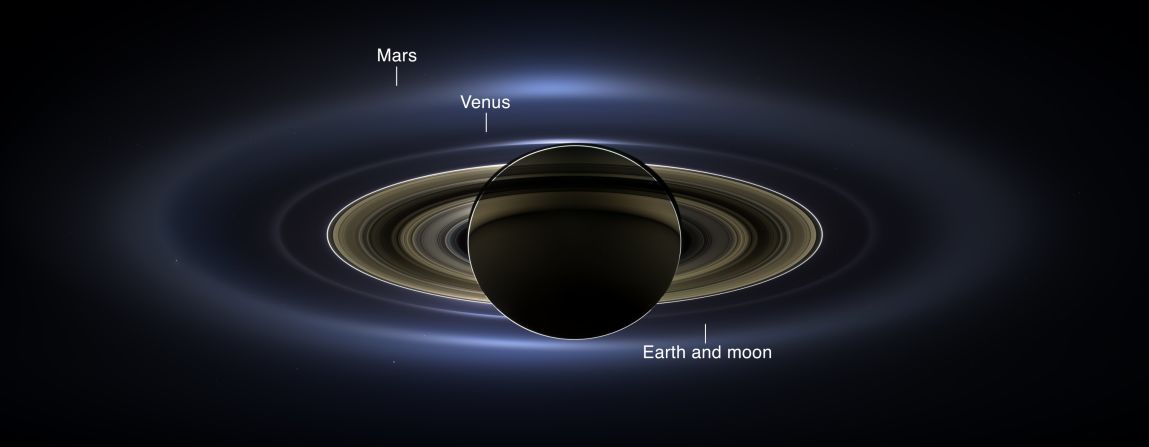

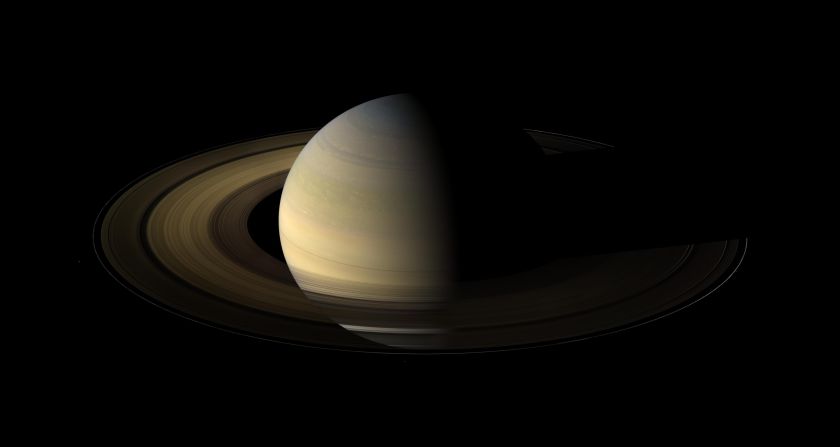

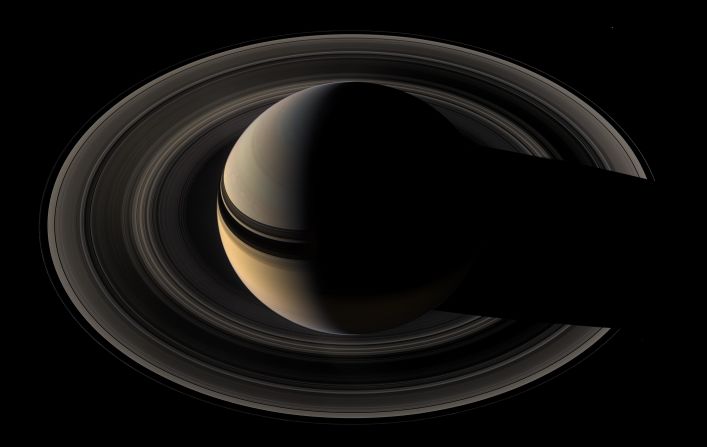

Although the Cassini mission ended by plunging into Saturn’s atmosphere in 2017, the data collected by the mission will fuel studies for years to come.

“This is a completely different explanation for the steep rims around those small lakes, which has been a tremendous puzzle,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini Project Scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “As scientists continue to mine the treasure trove of Cassini data, we’ll keep putting more and more pieces of the puzzle together. Over the next decades, we will come to understand the Saturn system better and better.”

Exploring Titan in the future

In June, NASA announced the latest mission in its New Frontiers program, called Dragonfly, which will explore Titan. It’s a Mars rover-sized drone, reaching about ten feet long.

“It’s the first drone lander and it can fly over 100 miles through Titan’s thick atmosphere,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in a statement. “Titan is most comparable to early Earth. Dragonfly’s instruments will help evaluate organic chemistry and the chemical signatures of past or present life. We will launch Dragonfly to explore the frontiers of human knowledge for the benefit of all humanity.”

The ultimate goal is for Dragonfly to visit an impact crater, where they believe that important ingredients for life mixed together when something hit Titan in the past, possibly tens of thousands of years ago.

Titan is similar chemically to Earth before life evolved, the agency said. They want to explore sand dunes on Titan to determine if they’re made of the same complex organic material discovered in the atmosphere.

“Titan has the key ingredients for life,” said Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division. “It has complex organic molecules and the energy required for life. We will have the opportunity to observe processes similar to what happened on early Earth when life formed and potentially conditions that could harbor life today. We can look for biosignatures.”

Once Dragonfly lands, it will spend two and a half years flying around Titan. It only has propellers, with skids to land, but no wheels to allow it to roam over the surface.

It will launch in 2026, but won’t reach Titan until 2034 because Saturn is so far from us.

Dragonfly will also explore Titan’s atmosphere, surface properties, subsurface ocean and liquid on the surface.