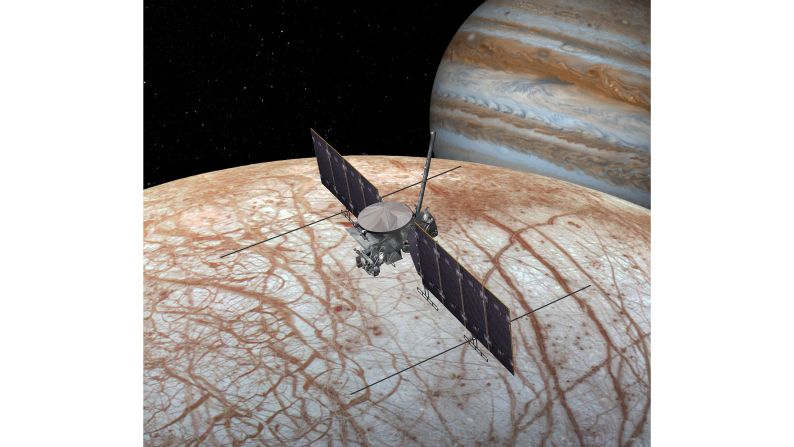

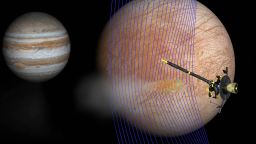

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission is entering its final design stage before construction and testing of the spacecraft and the scientific instruments it will carry to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa.

“We are all excited about the decision that moves the Europa Clipper mission one key step closer to unlocking the mysteries of this ocean world,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

Europa has been a high priority for scientists because, as an ice-covered moon with a subsurface salty liquid ocean, it has been identified as one of the ideal spots for hosting life in our solar system.

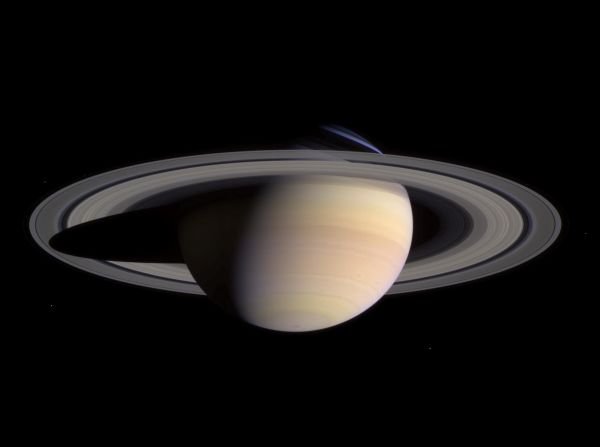

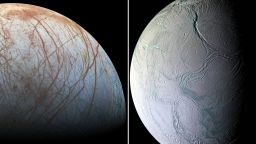

In 2017, NASA announced new evidence that the most likely places to find life beyond Earth are Europa or Saturn’s moon Enceladus. The icy ocean worlds contain intriguing chemistry and water plume activity. The Europa Clipper mission is also the first to explore an alien ocean.

“If there are plumes on Europa, as we now strongly suspect, with the Europa Clipper we will be ready for them,” said Jim Green, NASA’s director of planetary science.

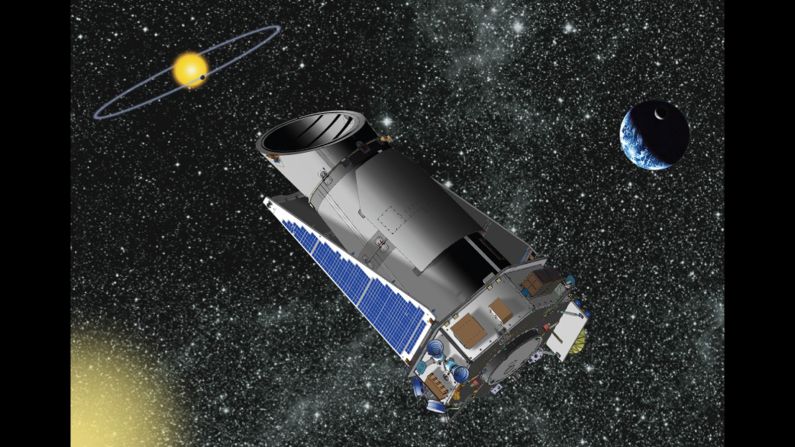

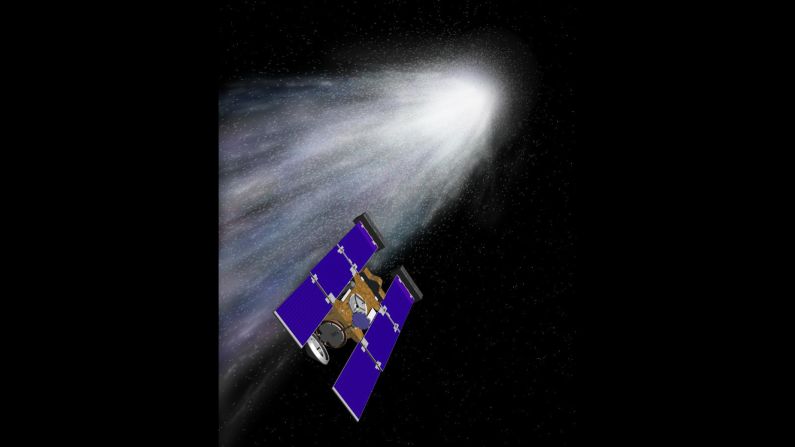

The Europa Clipper, named for the streamlined sailing ships of the 1800s, could launch as early as 2023, but a targeted launch has been set for 2025. It is expected to reach Europa after a journey lasting several years.

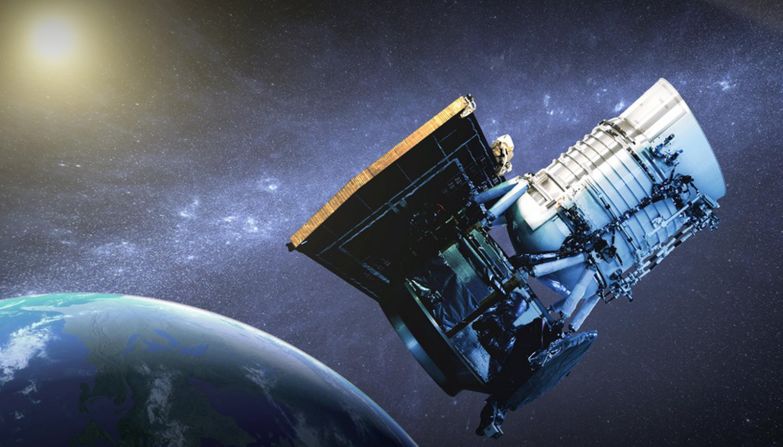

Europa Clipper will carry cameras and spectrometers to capture images and determine the composition of the moon. Ice-penetrating radar will measure the thickness of the ice shell covering the ocean and help search for the subsurface lakes believed to be there, much like those in Antarctica on Earth. A magnetometer can determine the strength and direction of the moon’s magnetic field to understand how deep the ocean goes and its salinity.

To investigate the possible plumes, a thermal instrument will search for eruptions or water particles in the atmosphere.

“We are building upon the scientific insights received from the flagship Galileo and Cassini spacecraft and working to advance our understanding of our cosmic origin, and even life elsewhere,” Zurbuchen said.

How Europa could host life

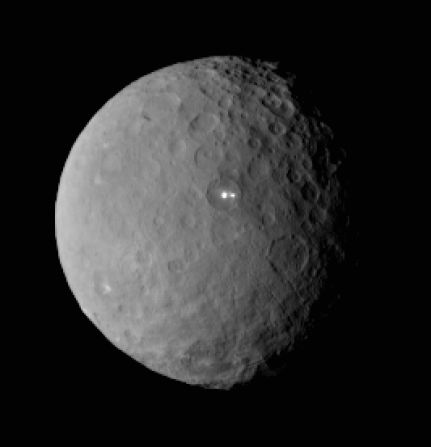

Research suggesting the possibility of an ocean on Europa was published as early as 1977, after the Voyager mission observed long lines and dark spots instead of a cratered surface similar to other moons. Then the Galileo spacecraft reached Europa in 1996 and revealed for the first time that there was an ocean on another planet.

During its closest flyby of Europa in 1997, less than 93 miles above the surface, Galileo collected signatures of changes in Europa’s magnetic field that the scientists didn’t understand, said Margaret Kivelson, professor emerita of space physics at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Last year, Kivelson and her colleagues took a closer look at that data. They realized that during the flyby, Galileo flew through a plume. This fortuitous happenstance is the best evidence of plumes to date, the study said.

The necessary ingredients for life as we know it include liquid water, energy sources and chemicals such as carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur and phosphorus.

But we’ve also learned that life finds a way to exist in the harshest of Earth’s environments, like vents in the deepest parts of the ocean floor. There, microbes don’t receive energy from sunlight but use methanogenesis, a process that reduces carbon dioxide with hydrogen, to form methane.

Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus show some of these key ingredients for life in their oceans, which is why researchers believe they are the best chance for finding life beyond Earth in our own solar system.

While Galileo didn’t know it was flying through a plume and was incapable of collecting material from it, Europa Clipper will be able to gather samples from plumes if it can fly through them. This would allow scientists a first look at the material inside Europa’s ocean that’s spewing through the icy crust and could reveal whether Europa’s ocean is habitable.

Europa Clipper’s instruments will be capable of “sniffing” the atmosphere of Europa, with more than 40 planned flybys. The flybys will be less than 228 miles above the surface of the moon, within the observed range of the plumes, which can reach 124 to 228 miles above the surface.

“If plumes exist and we can directly sample what’s coming from the interior of Europa, then we can more easily get at whether Europa has the ingredients for life,” said Robert Pappalardo, Europa Clipper project scientist. “That’s what the mission is after. That’s the big picture.”