A scorching heat wave is forcing Europe to realize how dangerously unprepared its cities are for climate emergencies.

Climate change is making heat waves increasingly common and more severe, putting the lives of thousands of vulnerable people at risk.

Hot weather gets deadly in places that are not ready for it. In August 2003, during one of the most severe heat waves seen in England in recent years, mortality across the country increased 16% because of the heat. But in London, 42% more people died compared to the average of the same time periods in the previous five years.

Temperatures in densely built-up cities tend to be several degrees higher compared to rural and suburban areas. The phenomenon, known as the urban heat island, is caused by the combination of surfaces that trap heat, low airflow, traffic and other heat-producing activities that happen in cities.

The difference tends to get bigger at night, as cities don’t cool down as much as rural areas.

Older people and children are particularly vulnerable to heat in the cities, but extreme weather affects everyone.

“Healthy people in general are okay in hot weather as long as they take some precautions, but when it starts getting to about 40 degrees Celsius (104 Fahrenheit) even healthy people are at risk,” said Bob Ward, policy and communications director at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, which is part of London School of Economics.

Productivity also dips significantly when temperatures increase. A 2018 study by Harvard School of Public Health found that reaction times of students sitting in a room with no air conditioning were 13% slower than those in cooler rooms.

It’s a problem that’s only going to get worse, because more people are moving into cities. According to the United Nations, 55% of the global population currently lives in cities. By 2050, that number will likely rise to 68%.

Europe is getting a taste this week of what the climate crisis has in store. France, Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic all saw temperature records shattered this week.

Cities were the worst hit. Paris implemented a special heat plan, designed to give its inhabitants relief. The plan was devised in the aftermath of the 2003 heat wave that killed 14,000 people in France alone. The city set up public cooling rooms in municipal buildings, put mist showers in the streets and kept parks and swimming pools opened longer than usual.

While the current European temperatures of just above 100 degrees Fahrenheit might not seem too high to some, they are way above the region’s seasonal averages.

And since most of Europe’s infrastructure and cities were built well before anyone was aware of the danger of climate change, that makes the heat wave even more dangerous.

“Cities that are used to more temperate climates, like London, are finding it very difficult to cope,” Ward said.

“Places which experience cold winters tend to worry more about insulation … but of course some of the measures you design to keep heat in during the winter can prevent heat escaping in the summer, making it even more of a problem,” he added.

It’s an acute problem in the UK, where one in five buildings overheats in the summer, according to the UK Parliament’s Environmental Audit Committee.

Kathryn Brown, the head of Adaptation at the Committee on Climate Change in the UK, told a committee hearing that temperatures in some British hospitals can exceed 30 degrees Celsius (86 Fahrenheit) when the outside temperature is about 22 degrees (70 Fahrenheit).

Buildings with dark surfaces trap heat because they absorb light instead of reflecting it. According to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, a dark roof reflects only 20% of light, compared to 80% that bounces back off a lightly-colored one.

It works with roads too. Los Angeles Street Services tested the idea of putting light-colored coating on otherwise dark asphalt public roads last year. It said the coating cut temperatures by between 10 and 30 degrees Fahrenheit.

But some solutions can make the situation worse. Air conditioning brings relief to those indoors, but it makes the outside even hotter by dumping hot air on the streets.

Even worse, it contributes to climate change. With an estimated 1.2 billion electric air conditioning units around the world (a number that is expected to triple by 2050), cooling technology could release enough greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere to cause temperatures to rise by 0.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, according to Rocky Mountain Institute.

That’s why scientists, architects and urban planners are desperately trying to find other ways to cool buildings and streets.

Creating more parks, green roofs and vertical gardens is one way to bring some relief. According to the Environmental Audit Committee, the surface temperature in an urban green space can be as much as 15 to 20 degrees Celsius lower than that of the surrounding streets, which makes the air temperatures 2 to 8 degrees cooler.

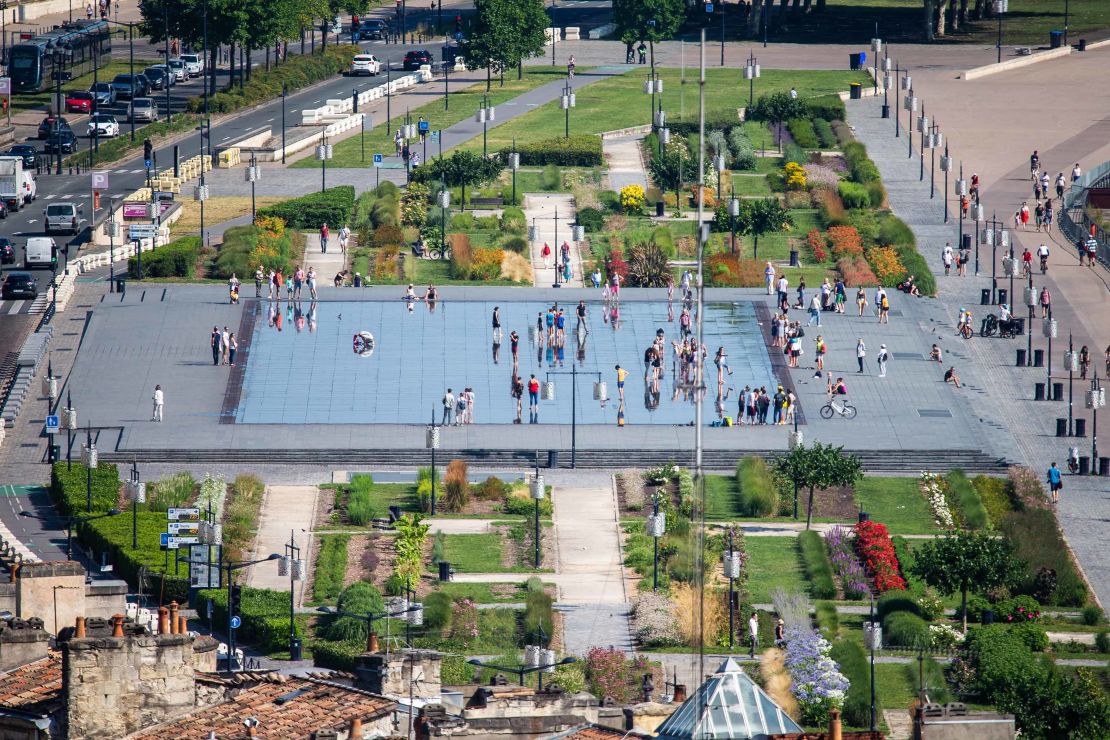

Water is another favorite – mist showers, fountains and reflective pools all bring the temperature down.

Simple shutters can also help keep heat away, as long as they are on the outside of the windows and prevent the light from getting inside.

They don’t need to be old-school either. London-based architecture firm Ahr covered a skyscraper in Abu Dhabi in dynamic flower-shaped shutters that change shape depending on the time of the day.

As the screens fold and unfold in response to the movement of the sun, they reflect up to 50% of the light. AHR said the screens reduce the need for significant artificial lighting and artificial air conditioning.