What started as a protest against an authoritarian President in Sudan turned into jubilation and dancing on the streets this year after he was deposed. But instead of the new beginning that protesters had yearned for, months of chaos and bloodshed have followed and dominated news coverage worldwide.

How did one of Africa’s largest nations go from ending a dictator’s brutal 30-year reign to deadly street crackdowns?

Here are some answers.

How did it all begin?

Everything started in December with the Sudan uprising.

The rallies began as demonstrations again the rising cost of food and shortages of fuel, but they morphed into protests against the President, Omar al-Bashir.

The movement started off on an optimistic note, with the nation’s women at the heart of the demonstrations and iconic images of them defying police brutality shared widely.

Why did they want Omar al-Bashir out?

Bashir’s legacy is one of human suffering and atrocities.

He took over as President of Sudan in 1989, after he led a coup that ousted the previous government. Though he’s technically been re-elected several times, human rights groups say the elections weren’t democratic.

Bashir isn’t exactly known as a benevolent leader. It was estimated that more than 15,000 villagers were killed by the government-backed Janjaweed militia between early 2003 and late 2004 in Darfur, and millions of Sudanese people were displaced. The Janjaweed militia was also accused of raping women in Darfur, and the government was accused of using chemical weapons against the community.

The International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor issued an arrest warrant in 2009 for Bashir on charges of genocide and war crimes related to Darfur. The court issued another arrest warrant in 2010 but in 2014 had to suspend the case because of lack of support from the United Nations Security Council.

That’s just scratching the surface. And through it all, Bashir retained power.

Then, the protests started late last year, and numerous deaths were reported as security forces used excessive force and violence against demonstrators, Amnesty International and others said.

“The situation is getting very bad – a lot of people dying. And they are torturing so many people,” one Sudanese demonstrator told CNN in April. “So, we are here to protest that and to ask the international community to stand with the Sudanese people.”

After months of protests, Bashir was arrested in April and removed from power in a military coup announced by Sudanese defense minister, Awad Mohamed Ahmed Ibn Auf.

A military council would take control to oversee a transition of power, he said.

He’s no longer in power, so why protest?

Giddy protesters initially celebrated Bashir’s ouster with dancing in the streets. Some had never known a time when he was not in power.

The excitement soon gave way to demands that the transitional military council make way for a civilian-led interim body and elections. To the protesters, it was time to hand power back to the people with democratic elections.

The military council and opposition groups originally agreed on a three-year transition to democracy, but talks broke down in May.

“All Sudanese people are in the street and demanding the downfall of the regime and not recycling the same people,” activist Omar al-Neel told CNN

Demonstrations will only end when the ruling generals transfer power to a civil transitional authority, protesters have said.

How have the demonstrations changed?

As violence continued to mark protests, a mass civil disobedience campaign also emerged nationwide.

The effort, which this week rendered the streets of the capital Khartoum mostly deserted, includes not going to work and “general civil disobedience for a civil state,” said the organizing group, the Sudanese Professionals Association, which also led anti-Bashir protests.

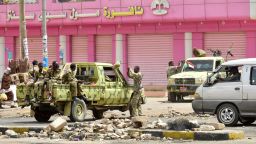

Meantime, the bloodshed has continued. Soldiers and paramilitary groups earlier this month opened fire on a pro-democracy sit-in in Khartoum, leaving at least 118 people dead, the Central Committee of Sudan Doctors said. The massacre horrified human rights activists and governments worldwide.

Sudan is sliding into a “human rights abyss,” United Nations experts said, calling for an independent investigation.

What’s the US doing about the crisis?

Critics have accused the White House of inaction as Sudan destabilizes.

After months of political turmoil, the State Department appointed a veteran diplomat as its special envoy for Sudan. The State Department is engaging with officials in the region and welcomes calls from the African Union, Egypt and Saudi Arabia for an end to violence and resumption of dialogue, the agency said.

Special envoy Donald Booth will lead the US push for “a political solution … that reflects the will of the Sudanese people,” the State Department said. He served as special envoy for Sudan and South Sudan from 2013 to 2017.

Booth is in Sudan this week with Tibor Nagy, the assistant secretary of state for African affairs, to meet with leaders and call for an end to attacks on civilians.