As Australia prepares for its election, campaigning is heating up on China’s biggest social messaging platform.

It’s the first time, social media experts say, that politicians from both of Australia’s main political parties are making a proactive push on WeChat to win over the country’s ethnic Chinese population, which has almost doubled in a decade.

They say it’s a positive step in engaging with a community which doesn’t always consume mainstream media and that has found itself caught in the political crossfire in the past.

But as WeChat increasingly becomes a campaign battleground ahead of Saturday’s election, it’s also become home to misinformation.

Some users have shared a screen shot of a tweet which appears to show Labor leader Bill Shorten – a frontrunner for Prime Minister, according to recent polls – saying: “Immigration of people from the Middle East is the future Australia needs.”

But there’s a problem: The tweet is not from Shorten’s verified account and his campaign told CNN he did not send that tweet.

Labor is so worried about the effect of false posts that it has written to Tencent, WeChat’s Chinese parent company, according to CNN affiliate SBS.

WeChat’s parent company Tencent did not respond to CNN’s questions on if it had received a letter from the Labor party, and what it is doing to prevent the spread of misinformation. However, WeChat users are able to download a filter to identify possible rumors, and can report groups if they are concerned by the content.

A new kind of campaign

During Australia’s last federal election in 2016, the eastern Melbourne electorate of Chisholm voted Liberal after almost two decades with a Labor MP. The winning candidate had an additional weapon in her arsenal: An underground campaign on WeChat.

WeChat boasts over 1 billion users worldwide, and has an estimated 3 million users in Australia according to marketing company Bastion China. Well-known figures and media outlets can make public posts, but most content is shared behind closed doors – either peer-to-peer, or in WeChat groups which can have up to 500 members.

There are more than 1.2 million Australians of Chinese descent – 5.6% of the country’s population – and almost 600,000 speak Mandarin at home, according to the country’s 2016 Census. A survey last year by Chinese media researchers Haiqing Yu and Wanning Sun found 60% of Mandarin speakers in Australia used WeChat as their main source of news and information.

In Chisholm, where almost 20% of residents are of Chinese ancestry, the Liberal party led a WeChat campaign in 2016 focused on three issues: Backing its management of the country’s economy, opposing same-sex marriage, and criticizing Safe Schools, a program to ensure schools are safe for all LGBTQ students.

“It was lowest-common-denominator politics,” the Labor candidate for Chisholm, Stefanie Perri, told The Guardian at the time. Gladys Liu, who spearheaded the Liberal Party’s WeChat campaign and who is a Chisholm candidate this election, said if Labor policies were good, they could dominate WeChat. “But Chinese don’t like their policies,” she told The Guardian. CNN has reached out to Liu for comment.

This time around, Labor is determined not to lose the battle on WeChat.

Haiqing Yu, who researches China’s digital media at Melbourne’s RMIT University, said Labor lacked a clear social media policy towards the Chinese community during the last election, while the Liberals used WeChat effectively and won. This election, there has been a clear change in Labor’s strategies, said Yu.

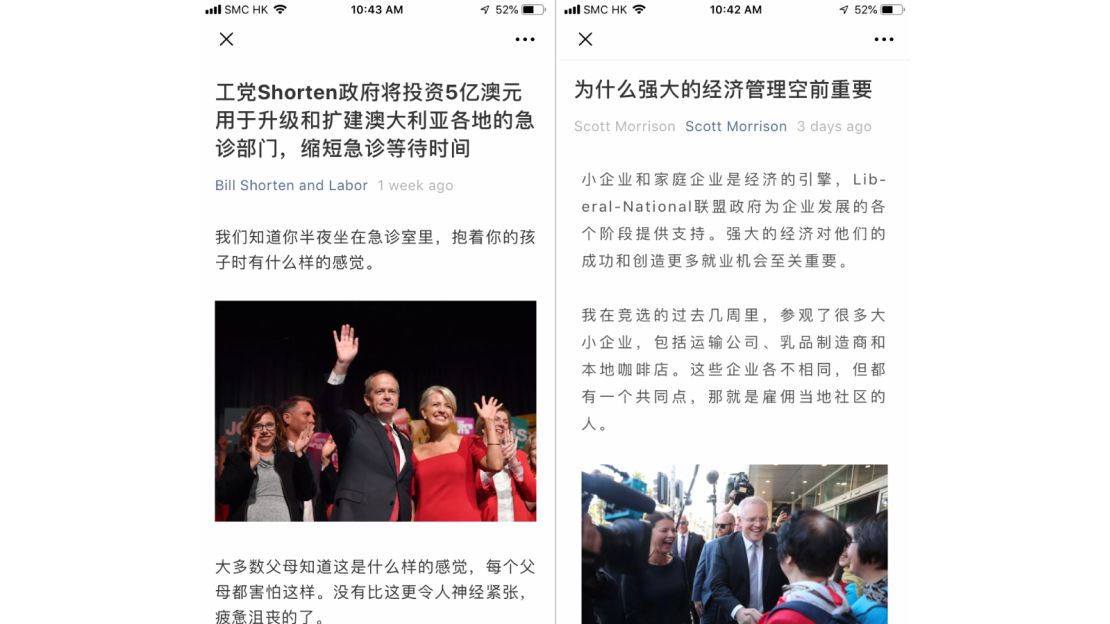

An account entitled “Bill Shorten and Labor”makes Chinese-language posts almost every day from the campaign trail, and Shorten has hosted a live discussion on WeChat, fielding questions from voters.

The Liberal Party, too, has been continuing its efforts to win Chinese Australians over. In February, Prime Minister Scott Morrison opened a WeChat account, and since then has been posting Chinese-language articles detailing his policies and encouraging people to vote for him.

Why target Chinese voters?

It might seem strange that politicians are devoting time and money to Chinese-language campaigns on WeChat: ethnic Chinese are still a minority in Australia, and politicians on both sides engage in anti-China rhetoric.

In a video that emerged in March of remarks made in September, Labor Party politician Michael Daley claimed that young Australians were being “replaced by young people, from typically Asia, with PhDs.” Daley apologized for his comments, and later stood down from his position as New South Wales Labor leader so as not to be a distraction.

In February 2018, former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd was lambasting the Liberal-led government, accusing it of launching an “anti-Chinese jihad” which had caused Chinese-Australians “unnecessary anxiety.”

Months before, in December 2017, Labor Senator Sam Dastyari resigned over his alleged interactions with a Chinese donor amid growing concerns over China’s influence on Australia’s political parties and university campuses. When he resigned, he insisted he always acted with integrity.

Labor joined WeChat in early 2017 as a way of “continuing our conversation with Australia’s Chinese community,” according to a campaign spokesman.

“Labor is the only party of government in Australia that proactively supports multiculturalism because we recognize our diversity makes us a stronger and a more cohesive nation,” the spokesman said.

A spokeswoman for Liberal Party leader, Prime Minister Scott Morrison, said they did not comment on campaigns.

But there’s another reason politicians might be targeting Chinese Australian voters. Many live in swing seats – and in what promises to be a tightly-contested election, these could be the key to victory.

Barton, Banks, Parramatta, Reid and Chisholm are all marginal electorates, and each have large ethnic Chinese communities that make up over 16% of their population. Together, those five seats alone have more than 150,000 ethnic Chinese – 12.5% of the country’s ethnic Chinese population.

Tony Pun, chairperson of the Multicultural Communities Council of New South Wales, said there was still a sense in the Chinese community that politicians were only engaging with them in a superficial way. “They only connect with us because they want our votes,” he said.

RMIT’s Yu said that in a way, politicians were killing two birds with one stone. In a country where politicians from both sides had previously engaged in anti-China rhetoric, candidates could win support from ethnic Chinese voters – and demonstrate their commitment to multiculturalism.

The spread of false content

Politicians can make public posts and communicate with their voters in groups, where they can address myths and rumors. But they can’t respond to everything – there are still many WeChat groups and chats they might not even be aware of.

In group chats seen by CNN, Chinese Australian voters discussed election issues and shared memes. Many were merely critical – such as a photo mocking members of the Shorten campaign who got stuck driving under a tunnel – but some are fabricated or misleading.

In addition to the doctored Shorten tweet, some users shared rumors about the impact of Labor’s promise to increase the number of refugees, and claims that a Labor government would close every power plant in the country.

A public account on WeChat posted a story that referenced other memes, including another of Shorten with red characters which read: “Green cards for all refugees!”

A paper published by cyber propaganda researchers found that the coalition government had also been targeted by online propaganda and much of it had come from accounts affiliated with the Chinese Communist Party, broadcaster ABC reported.

“It’s a problem that all social media platforms face,” said Sun, a professor of Media and Communication Studies at the University of Technology Sydney who specializes in Chinese media. “But WeChat makes it harder to trace the origin of the sender of information.”

Like WhatsApp, messages can be easily forwarded to numerous groups, with no sign of where they originated. Because most of the information is shared in private invitation-only groups, it’s challenging to monitor what is being sent.

A different ecosystem

In China, online content is heavily censored and WeChat is no exception. Messages deemed to have sensitive content – anything from the US-China trade war to the #MeToo movement, according to a Hong Kong University project – do not make it through.

Users in Australia who get their news mainly from WeChat won’t get the whole story.

“They exist in another ecosystem that’s shaped and largely controlled by the Chinese Communist Party,” said Adam Ni, an expert on China-related issues atMacquarie University.

This poses an issue for politicians using WeChat for debates. They may avoid topics deemed by Chinese censors to be off-limits, for fear of being blocked.

In a live forum on WeChat in March, Shorten was asked a series of questions about telecommunications giant Huawei, Chinese interference in Australia, and negative views in Australia of the Chinese Communist Party. He answered none of them, according to an ABC report.

In a statement to CNN, a Labor spokesman said the party had never experienced any censorship of its communications on any social media platforms. Shorten’s campaign told ABC, “We do not tolerate any outside interference that seeks to undermine our free and fair society.”

But Fergus Ryan, an analyst with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute who focuses on Chinese social media and censorship, said it was concerning that any discussion on WeChat was subject to censorship from Beijing by default.

“The whole process is so opaque that it’s difficult to know what is censored and what isn’t censored,” he said.

There are also security issues associated with the accounts, said Ryan. Both the current Prime Minister’s “Scott Morrison” WeChat account and the “Bill Shorten and Labor” WeChat account are registered to Chinese nationals. The “about” page of Morrison’s account says it was registered in January this year to a man in Fujian province, while the “Bill Shorten and Labor” account is registered to a man in Shandong province, and was originally set up with a name that references a tea garden.

The “Australian Labor Party” account, however, is verified and registered to the Party.

When CNN asked Labor if the account registration posed a security risk, a spokesman disputed the registration information, saying that it was operated by an Australian resident who is an AustralianLabor Party employee. Scott Morrison’s press secretary did not respond to a request for comment.

A growing interest

Despite security, censorship, and the spread of misinformation, Ryan said politicians should not stay off WeChat.

Instead, they should make an extra effort to communicate with Chinese-speaking voters using other platforms which are not censored.

“I do think it’s, from one perspective, good that they’re doing this outreach to one segment of the population,” he said. “It’s probably unreasonable to say that they shouldn’t use these platforms altogether.”

Wilfred Wang, a lecturer in communications and media at Monash University, believes the impact might have been overstated.

He pointed out that Chinese-Australians encompass a wide range of backgrounds, from people whose families have lived in the country for generations to international students.

While recent arrivals from mainland China would be likely to use WeChat, they might not be eligible to vote, most not being Australian citizens. “I think most Chinese voters won’t take those political related news on WeChat too seriously,” he said.

RMIT’s Yu said there were a range of views in the Chinese community about politicians engaging with them on WeChat. But one thing was for sure – Chinese Australians had shown unprecedented enthusiasm in this year’s election, she said.

“WeChat has definitely made it much easier and more open to engage in politics,” she said. “The Chinese community has grown bigger. It has strong views, is politically active, and looking for a voice and representation in the Federal Parliament.”