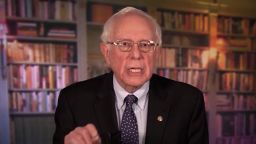

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders raised an eye-popping $6 million during the first 24 hours of his presidential campaign, far surpassing the totals announced by his rivals for the Democratic nomination

But another number he revealed Wednesday could prove crucial to his candidacy and a model for others: the $600,000 he said he’s received from people who have signed up to automatically donate to his campaign each month.

In a year’s time – just as Democrats in Nevada and South Carolina weigh in on the presidential nomination – this initial round of donors already will have contributed $7.2 million to Sanders’ presidential ambitions – with little effort or expense from his campaign.

This “subscription” approach to politics is an increasingly popular way for candidates to build a sustaining fundraising base.

About 20% of the money that flowed to Democratic candidates and organizations through ActBlue in the 2018 cycle came from recurring contributions, Caleb Cade, an ActBlue spokesman, told CNN. ActBlue does not disclose the fundraising details of the individual candidates who use its online platform.

But New York Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who entered Congress last month with the highest proportion of small donors of any House member, is one of the most prominent examples of a politician using recurring donations to fuel her campaign. In all, about 62% of her money came from donors who contributed in amounts of $200 or less, according to an analysis by the non-partisan Center for Responsive Politics.

“It’s like Netflix but for unbought members of Congress,” Ocasio-Cortez tweeted recently of the recurring contributions. She called it one of the “most important things people can do to get big money out of politics.”

Republicans, most notably President Donald Trump, also encourage recurring donations to their campaigns.

Presidential campaigns are expensive affairs.

Spending by President Barack Obama, his Republican challenger Mitt Romney and outside groups aligned with both men topped $2.3 billion in the 2012 election. Traditionally, presidential candidates raise the huge sums they need by wooing donors at private fundraisers in the moneyed corners of the country from Beverly Hills to the Hamptons.

How much time does fundraising absorb?

In 2016, then-Congressman Rick Nolan of Minnesota told “60 Minutes” that both political parties expected new lawmakers to spend a staggering 30 hours a week, dialing for campaign dollars. One campaign-finance expert, Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, who teaches at Stetson University’s law school even wrote a whole paper about Washington’s fundraising hamster wheel, which she dubbed “Time Suck.”

So, finding a renewable source of money frees up one of a campaign’s most precious commodities: the candidate’s time.

The Netflix subscription model “not only allows candidates to get some of their time back,” said Sheila Krumholz of the Center for Responsive Politics, “it also allows them to say, ‘I’m taking my campaign to the people.’ ”

While all the mechanics are in place for recurring political donations through platforms such as ActBlue, Krumholz notes that one thing hasn’t changed: a candidate still has “to generate the enthusiasm that excites small donors to sign up to give” in the first place.