The crisis in Venezuela appears to be shaping up like a Cold War-style confrontation: The Kremlin is throwing its support behind embattled Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, while Washington backs Juan Guaido, the self-proclaimed interim president.

The story at first glance seems to have all the elements of a spy thriller. In recent days, rumors have swirled about Russian mercenaries, massive bullion shipments and murky assassination plots.

Maduro has cast himself as a latter-day Fidel Castro in this drama. In an interview with Russia’s state-owned news agency RIA-Novosti, Maduro hinted at a US-backed attempt on his life, saying, “Without a doubt, Donald Trump gave the order to kill me, told the Colombian government, the mafia of Colombia to kill me.”

That sounded like an episode ripped from one of the CIA’s failed plots to kill the Cuban leader. And the crisis carries echoes of the Cuban Missile Crisis: Late last year, Russian bombers capable of delivering nuclear weapons flew to Venezuela, signaling that Russian President Vladimir Putin was willing to play in America’s backyard.

So are we about to watch a Netflix-era remake of the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion? Is Venezuela another arena for proxy conflict between Russia and the United States, much like the way Moscow and Washington back opposing sides in the Syrian civil war?

Certainly, Maduro’s conspiracy theories – and his language about resisting American neocolonialism – are reminiscent of the old contest between the US and the USSR in Latin America. But Russia is not backing his government in Venezuela to spread the ideology of Marxism. For starters, Moscow sees Venezuela in large part as a business proposition.

Russia’s state-controlled oil company Rosneft has been a major backer of Maduro’s government, and Russia and Rosneft have provided billions in loans and lines of credit for cash-strapped Venezuela.

Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA is covering almost all of those debts with shipments of oil. In a research paper published last year, analyst Julia Gurganus noted that Venezuela “has relied on Rosneft for prepayments of future oil deliveries to meet its financial commitments and to market physical volumes of Venezuelan crude to refiners in the United States and other countries.”

But in addition to Moscow’s economic bet on Maduro, there’s a geopolitical dimension to Russia’s interest in keeping the president in power. Russian state television in recent days has cast the Venezuela crisis in terms of US-Russian confrontation, sometimes comparing Guaido and the Venezuelan opposition to Ukraine’s pro-democratic Maidan revolution in 2014 or to the Arab Spring uprising that, among other things, toppled longtime Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi.

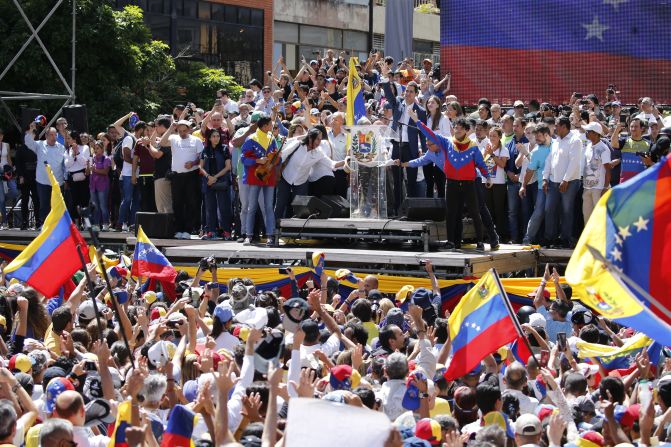

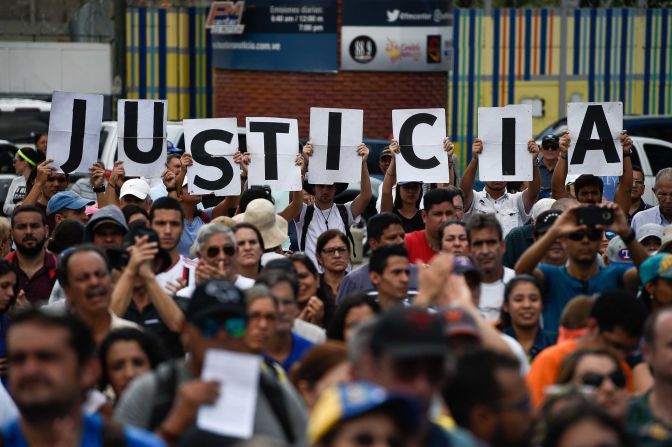

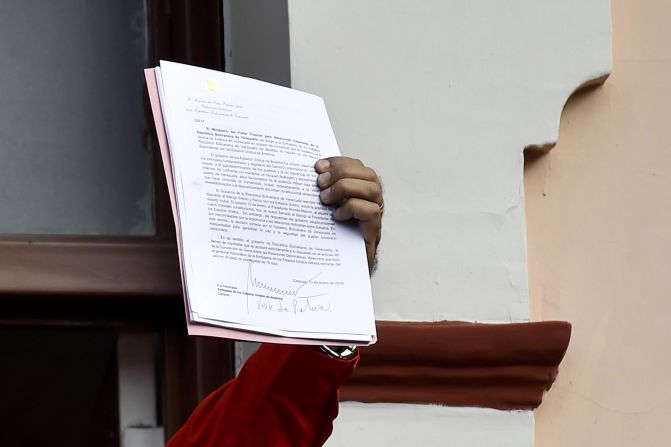

In photos: Venezuela in crisis

Russia spreads its global reach

The rhetoric mirrors official thinking in Russia, where the Kremlin routinely accuses the US of illegitimately pursuing a policy of “regime change” or “color revolutions” aimed at toppling Washington’s opponents around the globe.

“Going back to the days of [former US President] George W. Bush, color revolutions are a neuralgic issue for the Kremlin,” said Andrew Weiss, vice president for studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “And they have no shortage of people inside the Russian government who spin elaborate conspiracy theories or see indicators that the US goes around the world under the convenient flag of democracy removing regimes it doesn’t like.”

Weiss noted another rationale for Russia’s support for Maduro: Showcasing Moscow’s global reach.

“There is also a big thread in Russia’s behavior in Latin America that is aimed at rattling the United States and making Russia’s role seem larger than it actually is,” he said. “It’s part of a headgame … a way of saying, ‘We can cause trouble in America’s backyard.’”

Venezuela is a long way from Russia’s borders, and Moscow no longer has any military bases in the Western Hemisphere. But that has done little to discourage conspiracy theories.

Maduro, for instance, did not halt speculation that Russian private military contractors may have augmented his security detail when he said that he had “no comment” about whether Russian private security guards might be providing him protection.

Russia certainly has a track record of sending private military contractors to advance its foreign-policy aims. The Russian government has never fully and officially acknowledged the existence of private military companies such as Wagner, the shadowy Russian firm the US Treasury has sanctioned for recruiting mercenaries to fight alongside pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine. However, the existence of the group became more difficult to conceal after paramilitary contractors were killed in US airstrikes in Syria.

But Konstantin Kosachev, a Russian senator who heads the foreign affairs committee of Russia’s Federation Council, or upper house of parliament, cast doubt on Russians being brought in to protect Maduro.

“I don’t think that there will be a request directly for protection by Russia,” Kosachev told RIA-Novosti, adding that the army is on the side of the current president, and that Maduro himself expressed confidence that he was well defended.