Story highlights

New report shows overdose deaths declined in the six months leading up to March 2018, suggesting a plateau

President Trump will sign legilation aimed at combating the opioid crisis

As President Donald Trump on Wednesday signed sweeping legislation aimed at curbing the opioid epidemic, experts on the front lines hailed the bipartisan efforts on the opioid package, but cautioned about celebrating prematurely, especially when tens of thousands of Americans’ lives are at stake.

“Despite all the polarization, Democrats and Republicans were able to agree on a number of effective policies,” said Keith Humphreys, a drug policy expert at Stanford University who worked with Senate and House staff on the legislation. “That’s impressive that, at least on this issue, they were able to collaborate in a way they haven’t been able to do on anything else.”

Added Guohua Li, a professor of epidemiology and anesthesiology at Columbia University: “It is heartening to see our elected officials put national interest above partisan politics and join hands to tackle a public health problem. The legislation represents an elevated federal response to the opioid epidemic, including increased financial support and some sound and sensible policy initiatives.”

The Senate 98-1 passed a sweeping opioids package in early October. The House overwhelmingly passed its version of the bill 393-8.

Flanked by Cabinet members, families impacted by the opioid crisis, law enforcement officers and a bipartisan group of lawmakers, Trump signed the bill during a ceremony at the White House.

“Together we are going to end the scourge of drug addiction in America,” Trump said. “We are going to end it or we are going to at least make an extremely big dent in this terrible, terrible problem.”

Trump said he had secured an additional $6 billion in funding to combat the opioid epidemic – what he called the “most money ever received in history” for the issue.

On Tuesday Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar credited the President with focusing Congress on opioids so they could pass the bill. “His leadership has focused the entire federal government on the crisis—really, this is something where every Cabinet department from Interior to Education is engaged,” Azar said while speaking at the Milken Institute’s Future of Health Summit.

The wide-ranging legislation expands and reauthorizes an array of programs aimed at treatment and prevention, from finding new, less addictive drugs for pain management to expanding access to treatment for substance abuse disorders.

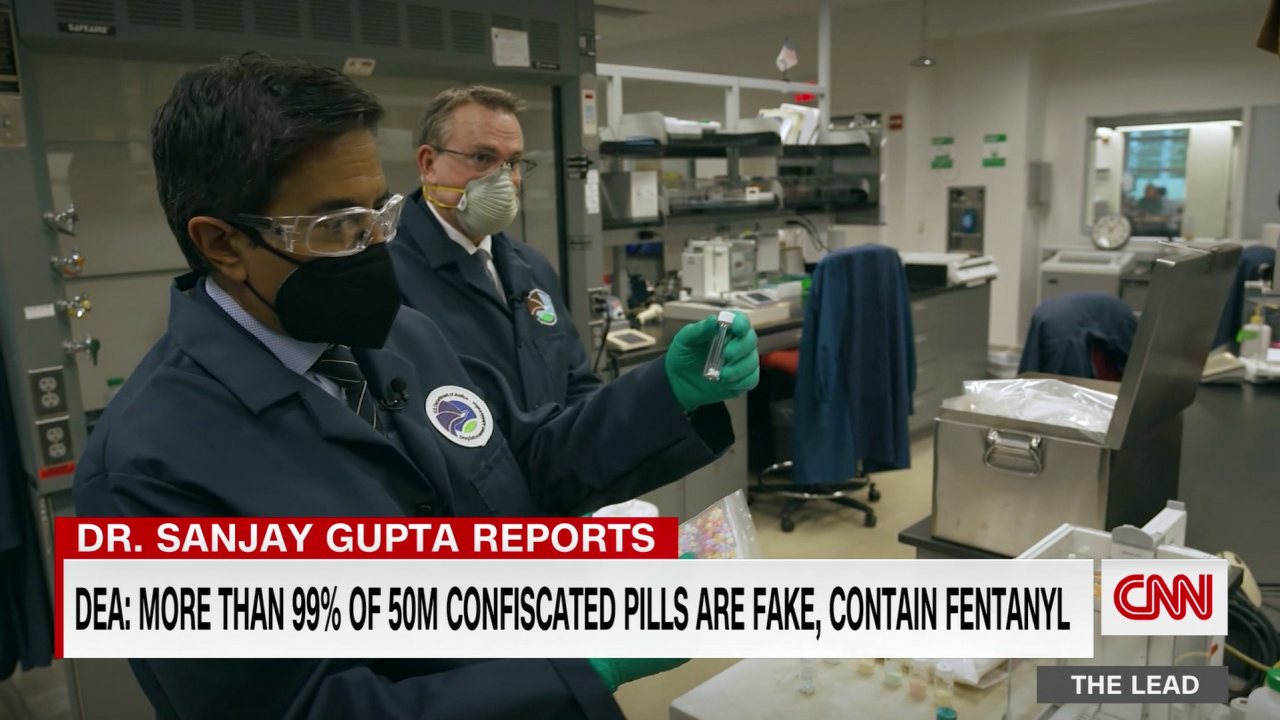

The measure also requires the US Postal Service to screen packages for deadly fentanyl from overseas; aims to prevent “doctor-shopping” by improving state prescription drug monitoring; and helps pregnant mothers struggling with addiction and their babies who go through opioid withdrawal.

A year ago, the Trump administration declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency, an action that set priorities in tackling the epidemic and has directed funds from the US Department of Health and Human Services to carry out that mission. Congress has allotted more than $6 billion for the opioid crisis. But experts say that isn’t nearly enough and that tens of billions of dollars are needed to back any such effort to combat the crisis.

More than 72,000 Americans died of drug-overdose deaths in 2017 – up nearly 7% from 2016, according to government data. Opioids contributed to more than 49,000 of those deaths.

New preliminary data published Tuesdayfrom the National Center for Health Statistics showed overdose deaths nationwide, while still exceedingly high, declined in the months leading up to March 2018, the most recent month for which data was reported.

“The seemingly relentless trend of rising overdose deaths seems to be finally bending in the right direction,” Azar said of the new report. “Plateauing at such a high level is hardly an opportunity to declare victory. But the concerted efforts of communities across America are beginning to turn the tide.”

Kelly J. Clark, the president of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, praised Trump for his efforts but said “there is much work ahead to ensure that all Americans living with addiction have access to treatment that is standardized and evidence-based, as well as comprehensive insurance coverage.”

The effectiveness of the legislation, experts said, will depend on how it’s carried out and whether prevention efforts are given priority.

“The recent opioid legislation that passed has the potential to make a small difference, but its potential effectiveness will depend on how the legislation is implemented,” said Dr. Lynn Webster, the vice president of PRA Health Sciences and the past president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine. “I think it is premature to celebrate victory when we experienced a record number of 72,000 drug-related deaths last year.”

Asked if the Trump administration has done more than any other administration to try to address the epidemic, Webster said, “I have not kept a ledger, but I doubt there has ever been a time in history when there have been more drugs smuggled into America, more overdose deaths, more people in treatment for substance use disorders, more emergency room visits due to drug overdoses, more people in pain who are under-treated or not treated, and a decreased life expectancy attributed to the number of people who have died from drug overdoses.”

“It is hard for me to see a metric that suggests much positive has happened under this administration other than a piece of legislation that has the promise to help if implemented as intended, but that is not the measure of success,” Webster continued. “It is a hope the future will be better.”

Webster said one of the greatest challenges ahead is the “lack of understanding the root causes for drug abuse and the way we manage the disease.” He said it was premature to guess whether the new legislation will reduce overdose deaths.

“If the focus is mostly on reducing prescribing and treating addiction, the outcomes will not be as successful as they hope,” Webster said. “We are already seeing, in many parts of the country, that methamphetamine overdose deaths exceed the number of opioid-related overdose deaths. This is happening because the disease of addiction is not about the drug. It is about the person and their environment.”

Li with Columbia expressed a similar sentiment. “The opioid epidemic is not the first epidemic involving controlled substances, and is unlikely the last one,” he said. “If we confine our response to short-term fixes of the opioid crisis, we may find ourselves soon in an epidemic involving a different drug, such as methamphetamines.”

Li did say the administration deserves credit for setting up a presidential commission to tackle the issue, declaring it a public health emergency and increasing federal funding by more than $4 billion – what he called “unprecedented in the 20-year history of the epidemic.” But he said he wished the efforts focused more on prevention, especially programs aimed at helping children.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“A national public health emergency warrants a public health approach, which should center squarely on prevention, in particular primary prevention,” Li said.

Stanford’s Humphreys said the nation needs to transform its healthcare system to “fundamentally take care of pain and addiction as the chronic disorders that they are.” But with Trump’s sharp attacks on the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid, he wasn’t too confident this administration was committed to such an effort.

“We need to accept that treating pain and addiction are part of the fabric of taking care of population health – and our healthcare system must be permanently equipped to do that,” Humphreys said.