Though it has been a divisive addition to Formula One cars this season, the “halo” proved its worth on Sunday during a spectacular opening-corner crash at the Belgian Grand Prix.

When Fernando Alonso’s car was sent airborne after a shunt from Nico Hülkenberg, the halo on Charles Leclerc’s cockpit deflected the impact of the Spaniard’s McLaren.

The titanium structure, built around the cockpit to protect drivers’ heads, sustained severe damage and left many wondering how bad the outcome could have been had it not been there.

Its addition to the sport, which was not without controversy, is just one of a multitude of changes introduced to F1 over the past decades to make the sport safer.

And some of those changes have come as a result of tragic accidents on the track.

READ: Formula One’s “halo” device proves worth at Belgian Grand Prix

READ: Sebastian Vettel wins Belgian GP after avoiding huge opening corner crash

Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger, San Marino 1994

Arguably the most high-profile crash in F1 history, Ayrton Senna’s death at the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix – just a day after Roland Ratzenberger was killed during qualifying – brought about some of the most sweeping changes seen in the sport.

A three-time world champion at the time of his death, Senna is still widely considered one of the greatest F1 drivers in history.

There were reports that the Brazilian was left so shaken by Ratzenberger’s death that he was contemplating whether he would even race in the following day’s grand prix.

The story of the 2018 F1 season so far

He ultimately decided to compete and on the day of the race, Senna lost control of his car and hit a concrete wall at an estimated 190 miles per hour.

The force of the impact sent part of the suspension back into the cockpit, fatally injuring Senna.

Some of the many changes implemented following his death included limiting engine size and power and raised cockpits sides to offer drivers more protection. Suspension also changed to prevent wheels from becoming disconnected.

READ: How paralysis fueled a love of motorsport

READ: Tatiana Calderon – Men “always expect a bit less from a girl”

Jules Bianchi, Suzuka 2014

So effective were the new safety measures, there wasn’t another F1 fatality until Jules Bianchi’s crash – and subsequent death nine months later – in 2014.

On lap 42 of a rain-drenched Japanese Grand Prix, German driver Adrian Sutil lost control and crashed his Sauber, prompting a recovery vehicle to be called out.

One lap later, Bianchi lost control on the same corner and crashed at 78 miles per hour into the 6500kg crane clearing Sutil’s car.

Following a lengthy investigation, the FIA deemed that there were several factors, rather than just one, which contributed to the Frenchman’s death.

These included the “semi-dry racing line” on the turn where both drivers lost control, Bianchi’s helmet hitting the underside of the crane and his failure to slow sufficiently.

Following the investigation, the FIA introduced the “four-hour rule,” – meaning races held during the day should take place no less than four hours before sunset – along with changes to track drainage and how emergency vehicles respond to crashes.

Niki Lauda, Nürburgring 1976

Niki Lauda had four of his fellow drivers to thank for making it out of his Nürburgring crash alive.

Bad weather and track coverage meant that parts of the Nürburgring circuit during the German Grand Prix were wet, while other parts remained dry.

Lauda lost control of his Ferrari on the notoriously dangerous “Bergwerk” corner and smashed into a bank of earth, causing the car to burst into flames and bounce back onto the track where it was then hit by Brett Lunger.

The American rushed over to Lauda, who was trapped in his car, and along with the help of fellow drivers Harald Ertl, Arturo Merzario and Guy Edwards managed to free him after a minute.

Initially able to walk away from the wreckage, the Austrian fell into a coma on the way to hospital having inhaled gases that damaged his lungs.

Lauda suffered severe and permanent burns to his head, losing most of his right ear and his eyelids but remarkably missed just two races and returned at Monza six weeks later, finishing fourth.

The crash happened at a point on the 22.8 km Nürburgring circuit that was near-impossible for rescuers to reach. It resulted in the track being pulled from the calendar the following year.

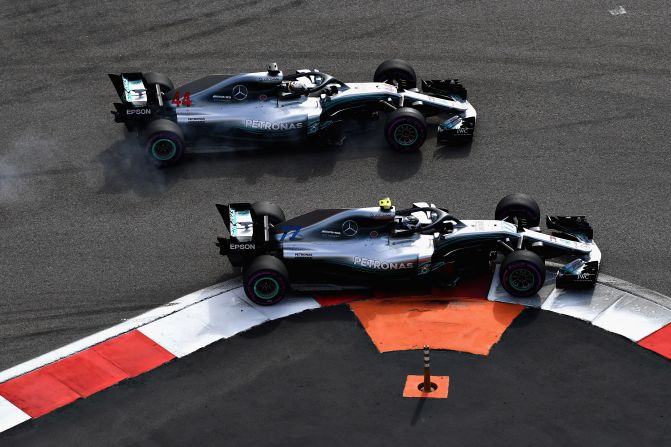

Thirteen drivers, Spa-Francorchamps 1998

If the five driver retirements after the first corner at Sunday’s Belgian Grand Prix seemed chaotic, spare a thought for the 13 who were wiped out within seconds in 1998.

The downpour at Spa that year was so heavy, most of the cars were barely visible on the television feed through the rain and tire spray.

Despite more than half the field crashing out, the race was restarted more than an hour later using the teams’ spare cars – though this rule has since been abolished to reduce costs in F1.

Four of the 22 drivers couldn’t restart the grand prix and there were several more incidents as the race wore on, including one that would impact that season’s world champion.

Michael Schumacher, trailing teammate Mika Häkkinen – who had already crashed out – by just seven points, tried to lap David Coulthard.

With the Scot’s car barely visible through the deluge, Schumacher smashed into the back of him and irreparably damaged his car, forcing him to retire from the race.

An angry Schumacher confronted Coulthard and the pair had to be separated. With just three further races to go, Häkkinen went on to win that year’s championship by 14 points.