Story highlights

The genome of an adolescent that lived 50,000 years ago had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father

This finding provides more insight about the interbreeding between the two hominin groups

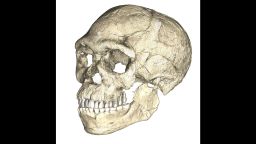

A 50,000-year-old bone fragment discovered in a Russian cave represents the first-known remains of a child that had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father, according to a new study. The study was published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

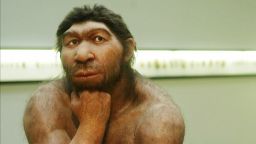

Neanderthals and Denisovans, the closest extinct relatives of modern human, are hominins that separated from each other more than 390,000 years ago. But separation doesn’t mean they didn’t encounter each other.

“We knew from previous studies that Neandertals and Denisovans must have occasionally had children together,” Viviane Slon, study author and researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said in a statement. “But I never thought we would be so lucky as to find an actual offspring of the two groups.”

The long bone, which belonged to a 13-year-old female, was discovered in 2012 in Denisova Cave. The cave, in Siberia’s Altai Mountains, is where other Denisovan and Neanderthal bones have been recovered.

Researchers were able to sequence the genome of Denisova 11, who died more than 50,000 years ago. Then, they discovered that she was a first-generation Neanderthal-Denisovan offspring, with equal contributions from both.

“An interesting aspect of this genome is that it allows us to learn things about two populations – the Neandertals from the mother’s side, and the Denisovans from the father’s side,” study co-author Fabrizio Mafessoni of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology said in a statement.

Denisovans pose particular questions for scientists because researchers have only a few bones that even point to their existence: a finger bone, a toe bone and a couple of teeth. Fossilized DNA sequenced from those bones, recovered in Siberia, has allowed us to learn more about them. But we still don’t know what these extinct hominins looked like.

Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA was sequenced completely for the first time in 2010, which led to the initial discovery that they were interbreeding with our ancestors.

Fifty thousand years ago, as modern humans moved out of Africa, they encountered Neanderthals and Denisovans, and “admixing” happened. About 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals and Denisovans were replaced by humans.

Before that, Neanderthals and Denisovans encountered each other even though they lived on opposite sides of Eurasia: Neandethals to the west and Denisovans to the east.

But pinning down exactly where it happened, and the extent of their interbreeding, has proved difficult.

The researchers were able to determine that the mother was more closely related to Neanderthals from western Europe, as opposed to a Neanderthal previously found who lived in the cave. And this occurred 20,000 years later than the Neanderthals living in the cave.

This suggests that Neanderthals were migrating back and forth across Eurasia tens of thousands of years before they disappeared. Meanwhile, the Denisovan father actually had a Neanderthal ancestor farther back in his family tree.

“So from this single genome, we are able to detect multiple instances of interactions between Neandertals and Denisovans,” Benjamin Vernot, study co-author with the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said in a statement.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Even with these encounters between the two groups, Neanderthals and Denisovans were able to remain genetically distinct because of their limited interactions, the researchers said.

“It is striking that we find this Neandertal/Denisovan child among the handful of ancient individuals whose genomes have been sequenced,” Svante Pääbo, lead author of the study and director of the Department of Evolutionary Genetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said in a statement. “Neandertals and Denisovans may not have had many opportunities to meet. But when they did, they must have mated frequently – much more so than we previously thought.”