Story highlights

An HPV test may be more effective at detecting precancer than a Pap smear, study finds

Experts remain torn on whether screening practices should change

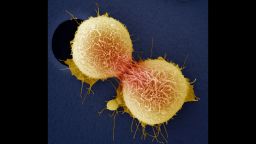

Cervical cancer is among the easiest gynecologic cancers to prevent, and two screening tests can help detect the disease early: the routine Pap smear and testing for human papillomavirus, or HPV.

The cytology-based Pap smear involves looking for cancer or precancer cells by testing cells taken from the lower end of a woman’s uterus, called the cervix. Diagnosing diseases by looking at single cells and small clusters of cells is called cytology or cytopathology.

On the other hand, a woman’s cervix also can be tested for the presence of certain high-risk types of HPV that can cause cancers, including cervical cancer.

Now, a study published in the journal JAMA on Tuesday suggests that cervical HPV testing may be able to detect signs of cancer earlier and more effectively than Pap smear over a 48-month period.

The findings are part of the Human Papillomavirus For Cervical Cancer screening trial, a publicly funded Canadian study.

“There has been a significant body of evidence that shows that by including HPV testing – as co-testing with cytology – we could improve detection of precancerous lesions of the cervix,” said Dr. Gina Ogilvie, professor and Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Global Control of HPV-related diseases and prevention at the University of British Columbia, who was lead author of the study.

“So this study is the next step, showing that by using only HPV testing in a screening scenario, four years later, women who received HPV testing were less likely to develop precancerous lesions,” she said. “The HPV virus is the cause of 99% of cervical cancers. By focusing on detecting the virus, we are then better able to determine which women have developed precancerous lesions and treat those earlier.”

In 2017, the US Preventive Services Task Force put forth draft recommendations to explore the idea of recommending screening every three years with cervical cytology alone in women ages 21 to 29 and then either continuing that testing or screening with HPV testing alone every five years, up to age 65. A final recommendation has yet to be published.

In 2012, the task force recommended screening for cervical cancer with Pap smear in women 21 to 65 every three years. Women 30 to 65 can screen with a combination of cytology and HPV testing every five years.

Cervical cancer is the fourth most frequent cancer in women globally, according to the World Health Organization. There were an estimated 530,000 new cases in 2012, representing 7.9% of all female cancers.

In the United States this year, the American Cancer Society estimates that there will be 13,240 new cases of invasive cervical cancer diagnosed, and 4,170 women will die from cervical cancer.

Weighing screening options

The new study involved 19,009 women across British Columbia who had no history of invasive cervical cancer. The women, ages 25 to 65, were randomly assigned to one of two groups between 2008 and 2012.

In one group, the women underwent HPV testing alone. In the other group, the women underwent routine cytology-based Pap smear testing. Lastly, if women in the HPV testing group received positive results for HPV, it was followed by cytology, whereas HPV-negative women underwent cytology screening at 24 months after their results.

All participants were invited to complete a demographic and behavioral questionnaire, which included questions related to their HPV vaccination status, sexual health and sociodemographic status, among other factors.

The researchers found that significantly more women showed signs of precancer cells in the first round of HPV testing compared with the Pap test group, despite the groups having similar questionnaire responses.

Referral rates for followup appointments related to concerning test results were significantly higher in the HPV testing group, at 57%, compared with the Pap test group, at 30.8%. By 48 months, those referral rates were lower in the HPV testing group, at 49.2%, compared with the Pap test group, at 70.5%.

“What this study could offer is confidence that the most important part of screening in co-testing is HPV, and health agencies can now consider whether offering Pap tests is good use of limited and scarce health dollars,” Ogilvie said.

“Offering women HPV [testing] for cervical cancer screening detects more precancerous lesions earlier, and also a negative HPV test offers more assurance that women will not develop precancer in the next four years,” she said. “This can mean that women may need to be screened less frequently but have more accurate results.”

Limitations of the study included that the women were mostly highly educated and primarily from two specific regions in British Columbia. More research is needed to determine whether similar results would emerge among a more diverse group of women.

The study was funded by Canada’s public research agency, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

A few authors of the study reported conflict of interest disclosures with ties to Siemens, a company behind an array of HPV tests, and Merck, maker of the HPV vaccine Gardasil.

Though the findings turn a new spotlight on cervical cancer screening approaches, they should not change current screening guidelines, said Dr. Mark Spitzer, medical director of The Center for Colposcopy in Long Island, New York, and past president of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Spitzer was not involved in the study.

“In the US, co-testing is currently the recommended gold standard, and neither doctors nor their patients should be willing to give up the added benefit you get from screening with a Pap test and HPV test together,” said Spitzer, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell.

“We have known from years of clinical research that primary HPV testing is more sensitive than cytology testing, a fact that was confirmed by this study. However, the study only compared primary HPV testing to liquid-based cytology,” he said. “There was no co-testing comparison group in the study.”

‘This could really potentially simplify how we screen women’

The study was “well-designed” and provides a much-needed comparison of Pap versus HPV testing, said Dr. Kathleen Schmeler, a gynecologic oncologist and co-leader of the HPV-Related Cancers Moon Shots Program at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, who was not involved in the new research.

“The bottom line is that this could really potentially simplify how we screen women and have it be more effective and not quite as complicated and burdensome – and opens the door for doing just HPV testing, which is actually what’s currently recommended by the World Health Organization for countries that don’t have Pap testing capabilities,” Schmeler said.

“They say if you don’t have Pap testing right now, don’t start Pap testing; instead invest in doing primary HPV testing, because it is that much more effective if it’s the only option that you have,” she said. “So these implications are important for North America, but they’re really important for the whole world. Cervical cancer is more common in lower-resource settings where people don’t have access to screening.”

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Dr. L. Stewart Massad Jr., a professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of gynecologic oncology at Washington University School of Medicine, wrote an editorial that accompanied the study in JAMA.

“What will replace the Pap test? In 2012, the American Cancer Society endorsed co-testing with cervical cytology testing and HPV testing at 5-year intervals as the preferred strategy for screening women 30 to 65 years of age because this approach combines the sensitivity of HPV testing with the familiarity of traditional Pap testing,” Massad wrote.

“However, the addition of cervical cytology testing adds little to the accuracy of HPV testing while increasing cost and false-positive results,” he wrote. “In 2018, organizations that develop cancer screening guidelines are wrestling with whether to recommend replacing co-testing with primary HPV testing as the optimal screening strategy.”

With this new study, that wrestling continues.