It’s baking hot in Okinawa, Japan’s southernmost island, but there’s no rest for the wicked.

Belting out songs in the midday heat, a group of women decked in colorful garb want to redefine what it means to be geriatric.

Meet KBG84, a band like no other: They’re all over 80 and count a centenarian as their most senior member.

” ‘Chomei da ne’ is an expression in Kohama. It means that everyone lives long,” Natsuko Maenaka, 84, says as she adds the finishing touches to her costume. Kohama is a small, remote island southwest of Okinawa.

“My father lived till he was 92, and at the time, it seemed like he’d lived to well over 100 years, but now that seems like nothing. We all live that long.”

KBG84’s ebullience and energy levels aren’t uncommon in Japan. It’s considered a “super-aged” nation, in which most of the populace is over 65. In 2017, there were an estimated 67,824 people 100 or older in Japan. And though centenarians are spread across the country, in Okinawa, their ratios are among the world’s highest: about 50 per 100,000 people.

With over 1,000 centenarians, Okinawa has earned a reputation as a “land of the immortals” and is one of five “Blue Zones,” areas around the world in which people live much longer than average.

So what’s the secret? Experts argue that though a combination of good genes and healthy lifestyles helps, there’s no specific formula.

“People tend to want to look for the magic thing that will make them look like an Okinawan, but there’s no single thing,” said John Roland Beard, director of the Department of Ageing and Life Course at the World Health Organization.

The KBG48 members attribute their energy levels to “ikigai,” or a “sense of life.”

That’s something they have bags of. They meet every month for rehearsals and practice a form of slow pop inspired by Kohama island’s traditional ballads. They’ve traveled as far as Tokyo and Singapore to perform, but they’re just as active back home, frequently working in sugar cane fields with their families to keep fit and try to stave off dementia.

Fitness has long been seen as an antidote to the development of dementia. A study in the medical journal Neurology suggested that high stamina, compared with medium, can decrease dementia risk by 88%.

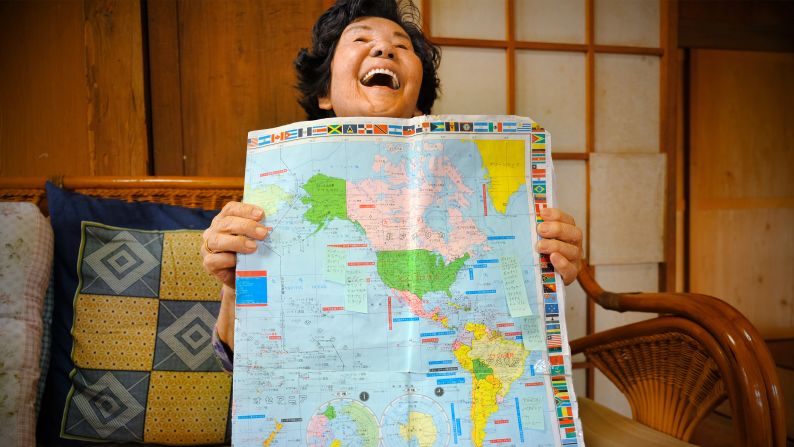

Maenaka also weaves and keeps mentally fit. Each time she sees something on television about a country she doesn’t know about, she looks it up on her map.

“When I saw the news about [North Korean leader] Kim Jong Un’s brother being killed in Malaysia, I didn’t know where that was, so I looked it up immediately,” she said enthusiastically.

But some fear that, as aging populations rise, favorable views toward the elderly are shifting.

Dr. Makoto Suzuki, an 84-year-old cardiologist and pioneering geriatrician, has studied centenarians for over 40 years. When Suzuki arrived in Okinawa from Tokyo in the the 1970s, he was initially surprised by how many healthy working centenarians he encountered. Of the 32 he met, none had dementia, and all were able-bodied.

Inspired by his find, Makoto established a “healthy centenarian” research group known as the Okinawa Centenarian Study. The center focuses on collecting data on the genes and lifestyles of elderly Okinawans.

Suzuki laments, however, that senior citizens aren’t as revered as they were four decades ago.

“Back then, 90% of the centenarians were regarded as treasures by their family members,” Suzuki said, noting that now many are regarded as more of a burden.

“They should have passed away, but advances in medical technology have kept them alive. That’s not just in Japan; it’s in the world over. Longevity isn’t seen as such a good thing across the world,” he added.

The dramatic rise in the numbers of centenarians in Japan after World War II has led people to view them as the norm, rather than the exception, Beard said. Hence, the shift in attitudes.

By 2020, there will be 13 “super-aged” countries, according to a 2014 report by Moody’s Investors Service. And as aging populations increase, the pressure to care for the elderly can put a strain on families as well as social systems. The International Monetary Fund predicts that the working-age populations in many mature Western economies will fall more than 20% between 2015 and 2055, along with their gross domestic product. But increasingly, silver populations do not necessarily spell disaster.

“It’s important to realize that older populations present challenges but also opportunities,” Beard said. “We need to shift away from the outdated stereotype that people retire and that’s that, to ensuring that older people can continue to participate in society.”

Suzuki agrees and has chosen to focus his research on what older people can do to stay healthy while continuing to contribute to society.

“We need longer-living, healthier, happier old people,” he said.

The geriatrician’s investigations into the secrets of a long, healthy life led to book called “The Okinawa Program: How the World’s Longest-lived People Achieve Everlasting Health – and How You Can Too” in 2002.

The book focuses on the importance of staying active, preserving the state of your mental health, belonging to a supportive community and eating a balanced diet.

But healthy eating isn’t just about what you consume, he says, but how you eat it.

That’s an idea Kayoko Matsumoto, an award-winning nutritionist, has long promoted at her Ryukyu cooking school in the city of Naha, where students can learn about the culinary traditions that have helped Okinawans reach 100 years. She imparts advice about how to cook vegetables like goya or bitter melon, a knobbly green vegetable rich in antioxidants, and sweet potato, which is rich in flavonoids, fiber and vitamin E.

On a tour of a local food market brimming with colorful vegetables and fruits, she singles out foods that form the stock for many dishes on the island, such as kombu, a kind of seaweed, and katsuobushi, dried fish.

“We add these ingredients into dishes so that they add natural flavor to them and reduce the need to use salt, which is bad for people’s health,” she said.

Matsumoto laments, however, that fewer young people have time to cook for themselves, given that most work full-time to support their families.

Businesses have been quick to adapt Okinawan food cultures to the modern age. Schools such as Taste of Okinawa Cooking are presenting trendier takes on traditional dishes and supplements made up of traditional herbs are becoming more popular.

It’s not just younger generations who’ve opted for faster vitamin and food options. Tomi Menaka, a 95-year-old member of KBG84, finds it more difficult to cook for herself and has few teeth left. Her family brings her food, but once in a while, she skips hearty fruits and fiber in favor of a more easily digestible fix.

In her kitchen, she gestures at two large cardboard boxes: one containing a large stash of instant noodles and another with a trove of energized vitamin drinks.

With a wide gummy smile, she holds up a colorful compact bottle.

“I drink one every day,” she said.