Story highlights

- The overall number of stillbirths and neonatal deaths decreased from 37,813 in 2007 to 33,457 in 2015

- Changes are probably due in part to a recommendation that elective deliveries wait till 39 weeks

(CNN)A recent drop in stillbirths and newborn deaths in the United States might be linked to an increase in term or near-term births, a new study suggests.

The study, published Monday in the journal JAMA Pediatrics, looked at more than 99% of US live births and stillbirths between 2007 and 2015 using data from the National Center for Health Statistics of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The data included approximately 34 million live births and 200,000 stillbirths. Full-term births take place in the 39th or 40th week of pregnancy.

Stillbirth refers to the death of a fetus at 20 or more weeks of gestation, while neonatal death refers to the death of a child within 28 days of delivery, according to the CDC.

The researchers found that the overall number of stillbirths and neonatal deaths decreased from 37,813 deaths in 2007 to 33,457 in 2015, an 11.5% drop.

"In the past decade, there have been some obstetrical interventions, as well as physician education, resulting in a decline in births at preterm or early term gestations," said Cande Ananth, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University Medical Center and a leading author on the study. "Indeed, what we found is that the decline in perinatal mortality was largely attributable to changes in the gestational age distribution."

Gestational age, or the age of the embryo or fetus, is typically calculated beginning at the first day of the mother's last menstrual period. It is often used to help assess how far along a pregnancy is and when the baby is likely to be born, according to the American Pregnancy Association.

The new findings may be good news for the United States, which has a notoriously high infant mortality rate among developed countries. According to a 2014 CDC report, the US ranked last out of 26 developed countries in terms of infant mortality for all gestational ages.

"These data are really encouraging ... But we still need to continue to work in order to reduce the overall burden of infant deaths and morbidity associated with preterm births in the US," Ananth said.

In addition to perinatal deaths, the study also looked at changes in the average gestational age at birth between 2007 and 2015. Specifically, women were classified as extremely preterm (20-27 weeks), very preterm (28-31 weeks), moderately preterm (32-33 weeks), late preterm (34-36 weeks), early term (37-38 weeks), full term (39-40 weeks), late term (41 weeks) or post-term (42-44 weeks).

The researchers found that birth rates decreased among all gestational age groups except one: the 39- to 40-week group. The percentage of women in this group rose from 54.5% in 2007 to 60.2% 2015.

"A recent study presented at the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine suggests that this is the optimal time for delivery," said Dr. Haywood Brown, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Duke University School of Medicine and president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

"So it's not surprising to see the number of deliveries during this time period increase."

These changes are probably due in part to a 2013 recommendation from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists that obstetricians postpone elective deliveries until 39 weeks in order to avoid some of the complications of preterm delivery such as breathing problems, heart problems and gastrointestinal problems, according to the Mayo Clinic.

"It became clear that early elective delivery prior to 39 weeks was associated with higher neonatal morbidity and mortality. As such, quality initiatives around early elective delivery were discouraged and hospitals adapted guidelines that discouraged elective delivery prior to 39 weeks," Brown said.

Preterm births account for approximately 70% of all newborn deaths and 36% of all infant deaths, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Risk factors for preterm delivery include a mother's history of preterm birth; problems of the uterus, cervix or placenta; smoking or use of illicit drugs during pregnancy; chronic conditions such as high blood pressure and diabetes; some infections; stressful life events; and physical injury or trauma, according to the Mayo Clinic.

"Other risk factors include older age and obesity," Brown added. "Clearly, the increase in obesity rates in pregnant women poses a greater risk for stillbirth."

For women at high risk of preterm delivery, a number of practices can help postpone delivery until 39 weeks, such as the use of a cervical cerclage or progesterone therapy, Ananth said.

For those women who may need to deliver earlier than 39 weeks for their own health and safety, there are also a number of ways to promote the maturity of the fetus during pregnancy. These include taking steroids such as betamethasone between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation to accelerate lung development, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

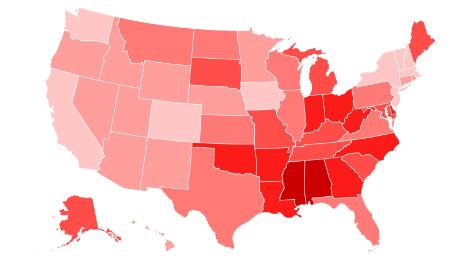

Some racial and ethnic groups are at higher risk for stillbirths and newborn deaths. African American women, for instance, have a 2.2-fold increased risk of stillbirth compared with Caucasian women, according to a 2009 study.

"African American women are known to have a higher risk for stillbirth at or near term, especially if comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension are present," Brown said.

But the new study did not look at differences in stillbirths or neonatal mortality between different racial or ethnic groups -- one of the study's main limitations, according to Ananth.

"We did not look at race-specific trends in this paper, although we did recognize race and ethnicity as a potential confounder," Ananth said. "That would be a topic worthy of investigation in the next set of studies."

But the results still suggest that -- assuming that the mother and fetus are in good health -- pregnancies should not be delivered earlier than 39 completed weeks, and doing so would lead to a decrease in overall perinatal mortality rates, according to Ananth.

"Preterm delivery rates have declined between 2005 and 2014 in the US and in several European countries," Ananth said. "So reducing the burden of early deliveries, and in turn improving perinatal survival, will be of tremendous benefit to society."