Story highlights

China's total fertility rate is below what is needed to keep the population steady

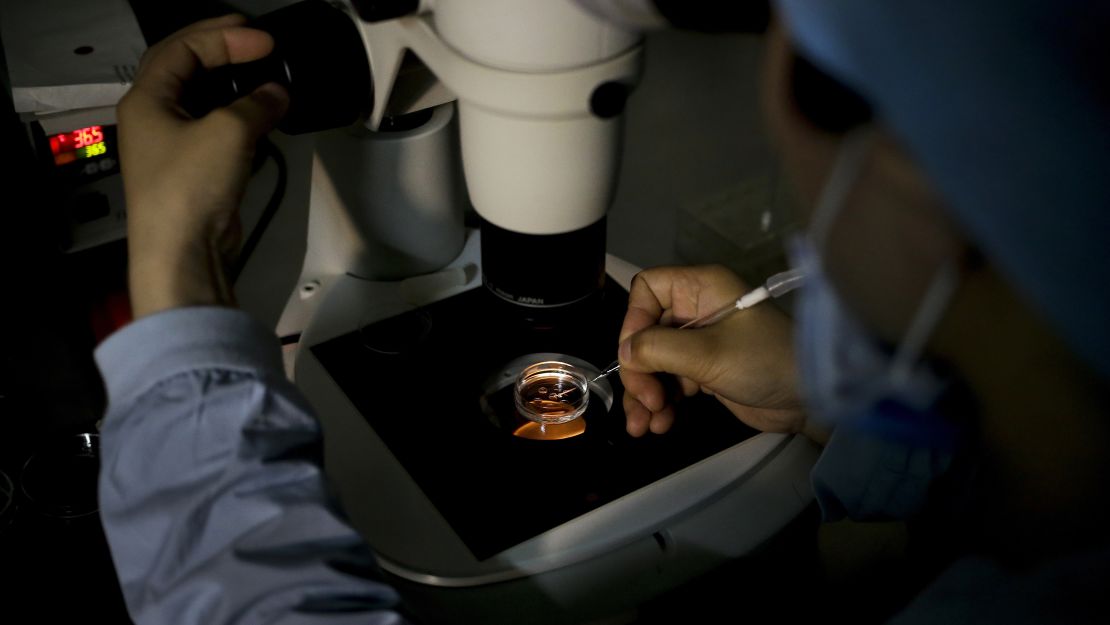

A decision to allow married couples to have two children is behind a surge in demand for fertility treatment

Xi Xiaoxin, 35, never thought that she would have trouble conceiving three years ago.

Back then, all she wanted was to enjoy traveling the world with her husband, whom she married in 2012. But when she came around to the idea of starting a family three years later, the road to conception turned out to be rough.

“Not until recent years did I realize that it could be so difficult getting a baby,” she said.

Xi is one of hundreds of thousands of largely urban Chinese women struggling with infertility.

Like elsewhere in the world, delaying motherhood has become more common in China, with high costs of living, long working hours, unfriendly maternity policies and high child care costs.Some specialists also suggest that environmental factors such as pollution could also be a factor, particularly for male infertility.

But it’s not just a personal struggle; it’s a national one.

China’s total fertility rate, at an estimated 1.6 children per woman in 2017, is similar to Canada’s but below those of the United States and UK. This rate is below the 2.1 rate needed to keep the population steady, according to the CIA World Factbook.

Chinese authorities want to boost the birth rate, but its population pyramid is upside down: There’s a shrinking number of workers to support an aging population.

To turn the tide, the Chinese government is making drastic changes to its population policies, which had long focused on keeping the birth rate low. In 2015, it scrapped the decades-long one-child policy, and this year, it abolished its long-feared Family Planning Commission, which enforced the draconian one-child policy.

But this decision to allow married couples to have two children is now behind a surge in demand for fertility treatment among older women.

Xi and her husband didn’t think about parenthood at all when they were younger. “Until these years … whenever I see my aging parents, there’s worry that they could be very lonely in the future with no grandchildren.”

Official data on infertility in China are hard to come by. A report six years ago by the China Population Association suggested that it affected 40 million women and men. Infertility is perceived to be much less of a problem in rural areas, where people get married much younger.

Struggles shrouded in silence

Phoebe Pan runs a help group for women struggling with infertility on social media platform WeChat.

“I know so many Chinese women who are overwhelmed by so-called infertility and sterility problems,” said Pan, who blogs about her experience on polycystic ovary syndrome, a hormone problem that can lead to female infertility.

She thinks age is the major cause of infertility problems among women.

Adding to the problem is the stigma surrounding infertility in Chinese society. Many of the women Pan has spoke to are ashamed to talk about it with families and friends, and this in turn causes a lack of awareness among young Chinese women.

Xi has undergone three years of various infertility treatments, including taking a bitter herbal medicine for three months, three rounds of ovulation induction therapy and one laparoscopic surgery to restore displaced tissues in her uterus.

This year, she decided to try IVF treatment in a state-run infertility clinic. It costs $4,700 – equivalent to about four months’ salary in rich cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou and a fee that’s not covered by state medical insurance, Xi said.

She found the experience in the state-run hospitals generally unpleasant. Xi and her husband have to get up early and visit the clinic every week and spend four hours there, mostly waiting in lines.

“The real consultation time lasts only five minutes,” said Xi, who also worries about the cost.

Reality TV show

Infertility is the subject of a new reality TV show, “The UFO Fertility Show,” which is set in a future when aliens have traveled back to Earth via UFO to explore why the human race is perishing.

The show began streaming online in China this year and was launched by physician Dr. Wei Siang Yu,who created the similar “Dr. Love’s Super Baby Making Show” in Singapore.

In the first episode, Yu’s team visits a couple in Shanghai and gives them advice on how to conceive. The tips include diet changes, tai chi-style exercises, rearranging the bedroom furniture and preventing noise. The host particularly frowned upon the pungent and sugary food found in the couple’s fridge.

The first two episodes of his show have attracted 46 million views altogether online, the company said.

“The government-run fertility clinics are far from enough,” Yu said.

The rise in demand for IVF today highlights the dream many parents once had but were forbidden from making a reality for more than 30 years.

As of 2016, there were only 451 clinics nationwide offering IVF licensed by the government, which means there are only 3.3 licensed fertility centers for every 10 million people in China, according to a report by Qianzhan Industry Research Institute. The report estimates that there are 800,000 men and women unable to access quality fertility treatment.

It also suggested that fertility clinics in China weren’t as successful as their counterparts elsewhere because of dated technology.

With a 30% to 40% conception rate, China falls behind countries like the United States, Thailand and Malaysia that have a 60% to 65% conception rate, the report said.

This has sent many Chinese abroad to pursue fertility treatment, with the US and Thailand the top choices.

Dr. Hal Danzer, a fertility specialist in Los Angeles, has a large Chinese clientele. He says people having babies later isn’t the only factor.

“I see a lot of Chinese businessmen who work 12 hours a day, six days (a week), and they don’t have a good diet. They are overweight. They smoke and drink a lot of alcohol. Their sperm don’t look good.”

Resorting to traditional and modern measures

Businesses sense opportunity in tackling the problem, with a renewal of interest in traditional Chinese medicine approaches towards infertility as well as the use of modern technology like apps and social media groups.

Fang,aphysician working in a government-run hospital in East China’s Zhejiang province, who didn’t want to give his full name, runs one of many online stores selling so-called fertility aids on Taobao, China’s biggest e-commerce platform. He said that he sells tens of thousands of homemade packs of foot soak herbs every month and that demand has been growingin recent years, far exceeding his expectation.

Though Fang admitted that the foot soaking is not magic, he thinks it improves his customers’ overall health and makes it more ideal for pregnancy.

In traditional Chinese medicine, the foot is considered crucial to maintaining health, he said

In contrast, people are also increasingly embracing cutting-edge technology to solve such problems. Pan said ovulation tracker apps are “very popular” among groups who receive fertility treatment.

One application that tops the app store list in China is Fengkuangzaoren, or “Crazy for making babies.”With a pink icon featuring sperm on a clock, the application provides an array of trackers such as basal body temperature, ovulation and menstruation to advise the best days to try to conceive. Its core feature, the company said, is an algorithm-powered IVF assisting tool that predicts total cost and success rate and brokers clients with local and overseas clinics.

The company said the app has accumulated 8 million users and has helped 70,000 families successfully conceive over the past four years.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

With the spirit of trial and error, women like Xi are not giving up hope. She is an active user of the app and a member of seven WeChat groups in which people share experiences of IVF treatment.

Xi is just starting her first round, so there could be a long road ahead of her.

“Although the process has been frustrating both mentally and physically, I believe, as long as there’s a ray of hope, we will persist on the road. We will have a child eventually,” she said.