Story highlights

A study looked at hundreds of football players, most of them with the brain disease CTE

The younger a player with CTE was when they started, the earlier their problems began

Sports may be a great way to keep kids active, but a new study of players finds that the earlier players with CTE started tackle football, the more vulnerable they were to emotional and cognitive problems.

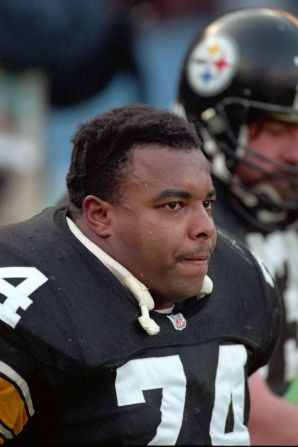

Researchers from the Boston University School of Medicine and VA Boston Healthcare System studied nearly 250 football players, of whom 211 were diagnosed with CTE after their death. CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, is a degenerative brain disease that often starts after repeated head trauma. Earlier studies have shown that the brain may change even after one hard hit.

Many football players have donated their brains to give researchers a chance to better understand this Alzheimer’s like-disease, which has been most commonly associated with former professional football players. Researchers are working on finding indicators that will help detect CTE in the living, but currently, the only way to diagnose it is with an autopsy.

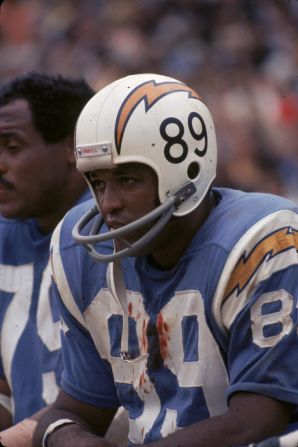

For the new study, published Monday in the journal Annals of Neurology, researchers focused on amateur and pro football players who are part of the UNITE (Understanding Neurologic Injury and Traumatic Encephalopathy) study, a retrospective analysis of professional and amateur athletes and veterans who had repeated traumatic brain injury before they died and to the VA-BU-CLF (Concussion Legacy Foundation) Brain Bank. The players’ careers varied in length.

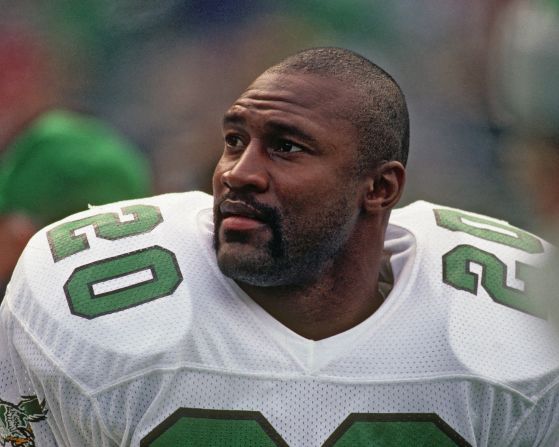

After phone interviews with families and friends, the researchers discovered for those players who had CTE, every one year younger the individual started playing tackle football predicted the earlier onset of behavioral and mood problems by 2.5 years and cognitive problems by 2.4 years.

That means they experienced earlier problems with memory and planning and organizing skills, they had emotional problems, and they struggled with depression and aggression much earlier than those players that started playing tackle football later. Playing tackle football before age 12 did not, however, seem to impact the severity of the CTE.

“What this study found was that playing tackle football lowers your resilience by about 13 years, and that is pretty profound, because that is a big difference,” said Dr. Ann McKee, chief of neuropathology at Boston VA Healthcare System and director of Boston University’s CTE Center, an author of the study.

This research is consistent with previous research that has shown a possible association between youth tackle football and problems with emotional and cognitive problems. It is sure to add fuel to the debate about when kids should start playing football, as even some former pros have started to call for an end to tackle football for children under the age of 13.

Kids who get brain injuries before the age of 12 seem to recover slower, research finds.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

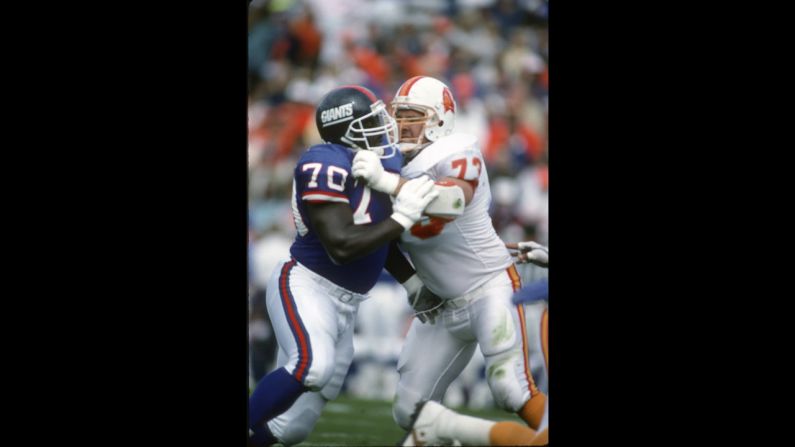

Polls have shown that a growing number of Americans believe that it isn’t safe for kids to play tackle football before high school, and some state lawmakers have tried to restrict the game to children 12 and up or even high school-age.

The researchers behind the new study emphasize that much more research needs to be done to determine whether studies like this can apply to the general player population. And more research is needed to figure out what long-term impact youth football may have on a player’s health.

Dr. Chad Hales agrees. The neurologist and assistant professor in the Department of Neurology at Emory University said that until there is a test or some kind of biomarkers that can pinpoint when and how CTE starts, it’s going to be a challenge to fully understand the nature of the disease.

“As the authors emphasize in the study, there are challenges with the way this information is collected. Right now, it’s all retrospective, for instance, and families have to fill out questionnaires, remembering information that may come from several decades back, and it’s hard enough for most of us to remember what happened last week,” said Hales, who was not involved in the new study. “That said, this does add to the data that is out there suggesting concern.

“In general,” he added, “we do know, it’s probably not a great idea to have little kids have repetitive head injuries.”

But until we know what injuries contribute to this pathology or how, it’s difficult to know whether there would be a safer way to tackle, for example, or to know what the age cutoff should be for playing the game. “I don’t think there is a way scientifically to answer that yet,” Hales said.