Artist Gunter Demnig works quickly and quietly. He kneels down to remove a slab of Berlin pavement and carefully replaces it with three small brass plaques, engraved with the names of the Boschwitz family. They lived here 75 years ago before they were sent to Auschwitz and murdered.

“For some people, it’s like a gravestone. They don’t have somewhere to grieve,” Demnig explains to CNN. “So this is a place to remember. It cannot be a gravestone but for some people it is like a gravestone.”

These are “stumbling stones,” Demnig’s extraordinary memorial to the more than 6 million killed in the Holocaust. The concept is simple: a brass plaque for every casualty of the slaughter.

He began 20 years ago and the idea has now taken him to more than 21 countries, installing more than 67 thousand plaques. It is the largest memorial of its kind in the world.

Someone once chided him about placing memorials that people could trip over. “I said, no. You won’t fall. But if you stumble and look, you must bow down with your head and your heart,” he said.

Far right slams ‘dictatorship of memory’

Germany has worked to ensure the horrors of World War II are not forgotten. The walls of the country’s parliament are still scarred with the anti-Nazi graffiti left by Soviet soldiers. And German schoolchildren are required to visit Holocaust memorials. But a backlash against the way history is taught has been brewing.

Germany’s nationalist, far-right party the Alternative for Germany (AfD) is challenging not just Demnig’s memorial but Germany’s “culture of remembrance,” which it has described as a “dictatorship of memory.”

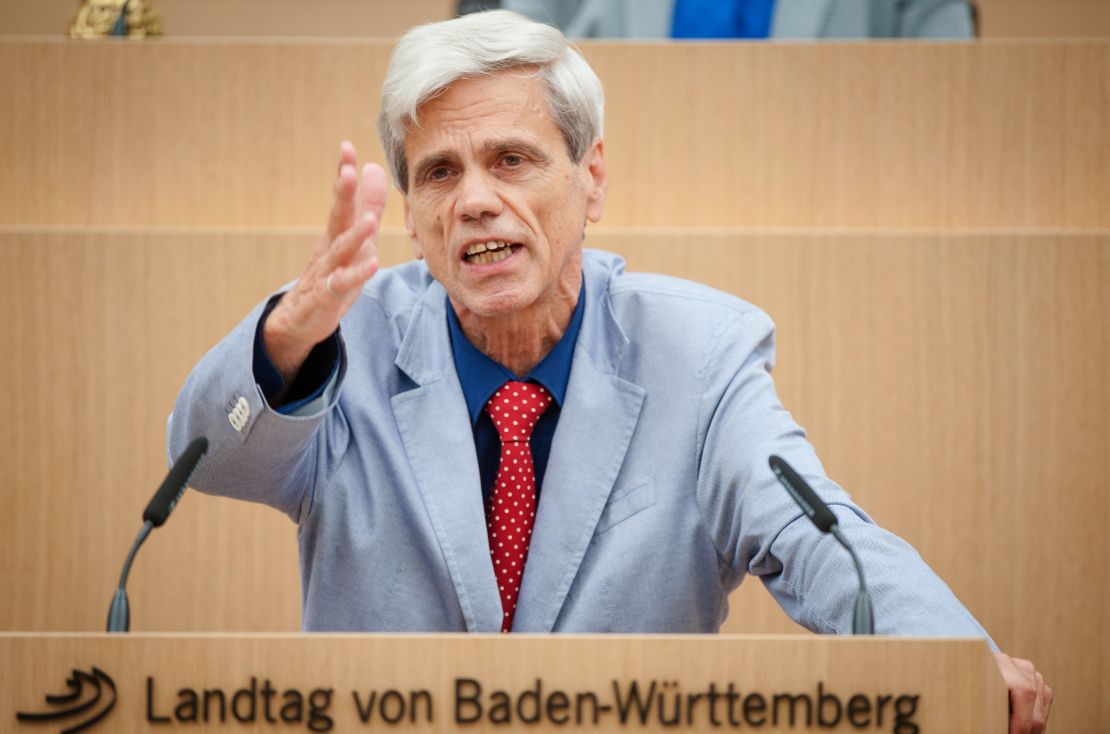

“With their actions, the stumbling stone initiators impose a culture of remembrance on their fellow human beings, dictating to them how they should remember who and when,” wrote AfD lawmaker Wolfgang Gedeon in a statement to his local parliament in February. “Who gives these obtrusive moralists the right to do so?”

On a cold winter morning in Berlin, a group of schoolchildren crouch down to watch as Demnig puts the finishing touches on the Boschwitz family stones.

They listen as Irene Weingartner explains why she wrote to Demnig requesting him to place the stumbling stones here: Her grandmother had befriended the Boschwitz family and their young son. When the parents didn’t return home one night in February 1943, her grandmother tried to reunite the boy with his parents, not knowing that they would all be sent to Auschwitz and killed.

“My grandmother was always terribly sad that she could not help this little boy. All my life I knew about it. So, it was important for me to tell other people,” Weingartner tells CNN.

How it works

One of the unique aspects of the stumbling stones is that it is a growing, grassroots memorial. Families and friends wishing for their loved ones to be memorialized write to the Stumbling Stones Foundation set up by Demnig.

His team researches and verifies the information to be put on the plaques then obtains permission from city governments to install them. Weingartner said it took more than a year for her request to be put through and she invited the local school to attend the installation.

“It seems like ancient history to kids,” she says, “But when they feel what happened to this child they will never forget it. And I hope they will help them to challenge injustice, racism and hatred in the world.”

The memorial has a clear impact on the children, who place flowers on the stones and write notes.

One boy says to his schoolmate: “He was only eight years old when he learned his parents would never come back.”

His friend replies, “That’s only two years younger than us.”

But even at this small gathering, there is a tension. An irritated man tries to push a pram through the crowd and mutters to no one in particular: “What is all this? Another stumbling stone? We already have too many!”

Since the project started, nearly 400 stumbling stones have been stolen and the number is on the rise. Police are investigating neo-Nazi gangs as possible suspects in the thefts.

Subject of debate

Wolfgang Gedeon’s call to ban stumbling stones in his constituency was rejected by the local mayor, but it sparked a debate in parliament about how Germany should remember its World War II history.

The far-right AfD party is now the largest opposition party in parliament and its lawmakers have become increasingly vocal in their demands, not only to put an end to immigration and ban Islam, but also to revise Germany’s remembrance culture.

Alexander Gauland, the head of the AfD’s parliamentary wing, has openly praised the “achievements” of Nazi German soldiers.

And when Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, a Holocaust survivor, addressed the Bundestag in January to praise Germany’s “generous brave and human gesture” to take in modern-day refugees, AfD lawmakers sat in stony silence and refused to applaud.

Gedeon declined CNN’s request for an interview. When Demnig is asked how he views Gedeon’s complaint, the artist laughs it off: “That’s their normal way. But we will continue this for the young people. That’s the idea: We do it for the young people.”

Irene Weingartner has harsher words: “Those people who think they are very good Germans are bad Germans if they refuse to remember what has happened in Germany and by the German people.”

Demnig knocks the dirt from his legs and adjusts his trademark wide-brimmed hat before picking up his bucket of tools. He heads to his next installation, where a family reunion with members from Germany and Argentina has taken place so they can watch him install plaques to their grandparents.

They come with flowers and hold a small ceremony as he hammers in the stones and gently wipes the plague to reveal the family name. When he’s done, Demnig tries to slip quietly away but is clearly embarrassed when one family member presses a bouquet into his hands. He prefers the focus to be on the stones, but he is proud of what he has accomplished so far.

“I have had people tell me this: Now, I can come to Germany again,” he says. “And yes, I am proud of that.”