Daniel Hahn’s swearing-in ceremony last August as Sacramento’s first African-American police chief was a celebration.

A gospel choir sang the National Anthem. The crowd cheered after its native son, who grew up in a historically working class and mostly black section of the Northern California city, pledged his oath.

He was “our Barack Obama,” said Ernie Daniels, a retired African-American police captain in Sacramento who mentored Hahn.

“Finally, we were able to get somebody that’s from our community,” Daniels, 68, said this week. “Everybody was so proud.”

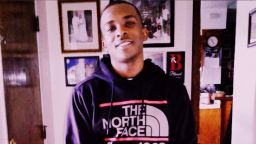

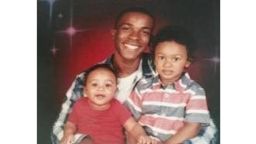

Now, Hahn, 49, who took the reins at a time of already strained relations between police and residents, finds himself in the national spotlight after the fatal police shooting of Stephon Clark. The 22-year-old unarmed black father of two who was gunned down by police in his grandmother’s backyard more than a weekago. The deadly incident, unfolding against the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement, was at least the third high-profile killing of a black man by Sacramento police in two years.

Protests against Clark’s killing harked back to those two cases, which spawned demonstrations when the Sacramento County District Attorney’s Office concluded that officers’ actions were justified.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra will hold an independent investigation into the shooting, Hahn told reporters Tuesday. The chief said he requested the oversight of state prosecutors, even though he had confidence in his detectives to be impartial.

Rev. Bob Balian, a Sacramento pastor who joined Hahn and community leaders on Tuesday, called Hahn “the chosen one.”

“We all wanted Chief Hahn in this position,” said Balian, who also presided over Hahn’s swearing-in last year. “Chief Hahn is the messiah. And we need to give Chief Hahn, we need to give the attorney general, we need to give the mayor and now we need to give the Justice Department every opportunity to go through this investigation.”

When Hahn was sworn in back in August, he said he wanted everyone to be able to trust his department, which serves a city of almost half a million people, only about 13% of whom are black. He acknowledged that some people were frustrated with law enforcement, did not trust them and believed police did not care about them.

It’s time to have hard conversations “to ensure that every corner of our city feels valued,” he said at the time.

In the wake of Clark’s killing, Hahn echoed that notion, even as his own – and his department’s – response in the case continues to come under scrutiny.

“This is my city,” Hahn told CNN. “This is the only community I’ve ever lived in.”

“I care about this department and I care about this community,” he said. “And I know for a fact that we can create a great relationship in every neighborhood in this city.”

“Incidents like this take us a step back,” he said.

Shooting stokes new suspicion

The officers who shot Clark were responding to a report that a man who’d broken car windows was hiding in a backyard, police have said. They shot Clark because they believed he was pointing a gun at them, police have said, but investigators only found a cell phone near his body. Two officers – one of whom is black – have been placed on administrative leave amid a use-of-force investigation.

Angry protesters took to Sacramento’s streets twice last week, blocking an interstate and the entrance to an arena during an NBA game.

Police released footage of Clark’s shooting 72 hours after it happened, and Hahn said authorities must continue to gather facts and conduct a thorough investigation.

In the footage, someone can be heard telling officers to mute their body cameras. The comment comes about seven minutes after Clark was shot multiple times – and it has not sat well with the community.

Hahn told CNN he doesn’t know why the cameras were muted. Officers are allowed to do so in specific situations, like when they’re talking to a confidential informant, he said.

“The bigger question, even beyond this specific case, is if we should allow people to mute their mics at all or under those circumstances,” he said Tuesday. “We were already looking at that before this incident happened, but I think this incident is a perfect example of why that is problematic.”

“Any time there is muting on this camera, it builds suspicion – as it has in this case. And that is not healthy for us in our relationship with our community,” Hahn told CNN affiliate KCRA.

It’s a bond that has frayed since officers in April 2016 shot and killed Dazion Flenaugh, 40, after he bolted from a squad car, grabbed a pick ax and swung it, police said, according to CNN affiliate KTXL. Police said Flenaugh, who was detained after residents reported seeing him acting suspiciously, was armed with knives and on drugs when he charged at them, the station reported. Flenaugh’s father said he was bipolar.

Three months later, Sacramento police officers fatally shot Joseph Mann, 51, who was mentally ill, after they tried to run him down with a cruiser. Callers to 911 had reported a man armed with a gun and a knife, according to recordings police released. Police videos from that day show Mann walking down the street, making strange gestures. When he was shot at least 14 times, Mann had a knife – but no gun.

‘We had a shining star’

Hahn was a baby when Mary Jean Hahn, a white woman reared in Minnesota, adopted him. She moved from the more affluent Fair Oaks area of Sacramento to predominantly black Oak Park because she wanted her son to grow up in a black community, said Charles Wesley Garrison, a family friend.

When Daniel Hahn was 16, he punched a wall after his mother scolded him for doing poorly in school, Hahn told The Sacramento Bee last July. Mary Jean called the police, and her son was taken into custody. He was booked for resisting arrest and spent four hours in a juvenile hall, the newspaper reported.

The encounter set Daniel Hahn on the right path, Garrison told CNN this week.

Three years later, while attending Sacramento City College in 1987, he joined the Sacramento police “by accident,” he told the crowd at his inauguration.

“Someone took a chance on me,” he said.

Veteran officers, like Daniels, saw promise in Hahn. They encouraged him to do everything he could to eliminate barriers to promotion. Still with the force, he graduated in 1995 from California State University Sacramento with a bachelor’s degree in business administration, then earned his master’s in public administration from National University.

“We saw that we had a shining star there,” Daniels said, noting Hahn’s “Hollywood good looks.” “I put him on every poster that we had.”

Hahn became police chief seven years ago in nearby Roseville, California. When he returned to lead the Sacramento department, he reportedly lived in south Sacramento with his wife and two children.

Mary Jean, a longtime community activist, lived long enough to stand at her son’s side as he was sworn in last August. She died last month at age 78.

“I’m here because my community carried me here,” he said at the swearing-in ceremony. “I’m here because the heart of Mary Jean Hahn willed me here.”

Tapping into the neighborhood

Hahn’s supporters have faith that he’s the right person to mend the rift between skeptics and the police department because he trusts residents.

Councilwoman Angelique Ashby said he reached out to her a decade ago when police were trying to solve a homicide in the Creekside neighborhood, where she headed the neighbors’ association.

“It was his instinct to call me,” she said this week. “I was just a community leader, but he saw great value in that.”

A resident’s surveillance system eventually led to an arrest in the killing. Hahn also called Ashby to plan a community meeting to address a rash of burglaries. Her participation was vital, Ashby recalled Hahn saying, so she cut short a vacation to be there.

Hahn also oversaw a criminal justice academy at several Sacramento high schools, said Sonia Lewis, a former criminal justice program teacher who is now a chapter leader of Black Lives Matter Sacramento.

Hahn “fought for kids in that program,” she said, and supported initiatives like a crime-scene investigation class and a week-long trip for students to New York and Washington.

‘The system has to want to change’

Hahn took over a department already working to improve, particularly in light of Mann’s killing.

City officials had mandated de-escalation training and bias training for officers. The city now requires the release within 30 days of all videos of officer-involved shootings, in-custody deaths and complaints reported to a city public safety accountability office, as long as the video does not hamper an investigation.

“We have also made some pretty sweeping changes,” Ashby said. “What’s frustrating and heartbreaking is that it wasn’t enough in this instance to save Stephon Clark.”

Lewis, who is Clark’s relative, said she believes Hahn has good intentions but doubts his ability to effect change in a system she believes has been corrupted by implicit bias.

“It makes it difficult for one man to effectively change the system. The system has to want to change,” she said.

“This is definitely going to be a test ground for him,” Lewis added. “Do I hope he passes the test? What I ultimately hope is that change comes.”

Ashby, too, said Hahn faces a critical moment.

“It’s tough for all of us. … Everyone’s watching Sacramento,” she said. “If any city can figure it out, it’s Sacramento because we have everything it takes to figure this thing out. … We’ve got the right chief, we’ve got the right city council. We have the right community.”

CNN’s Ray Sanchez contributed to this report.