Amanda Thomashow was hopeful as she left a meeting with Michigan State University officials in 2014 about Larry Nassar.

She had shared with them one of the most intimate, painful experiences of her life, and she felt like they had listened. They took notes and expressed disgust, she said, as she described how the renowned sports doctor touched her in ways that made her uncomfortable during an exam.

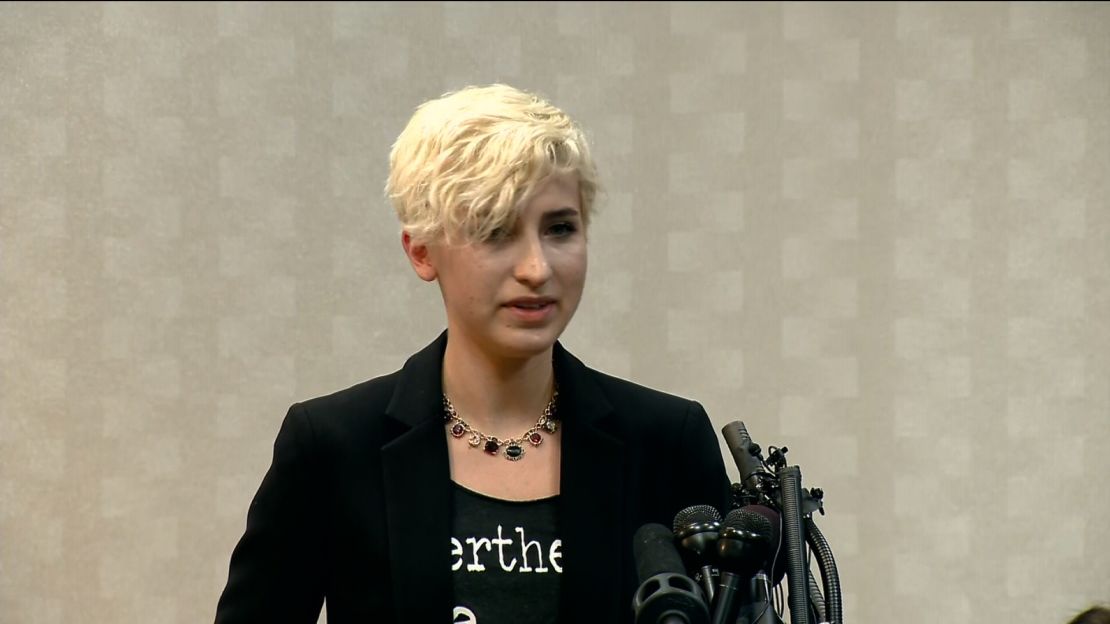

Thomashow was the first woman to file an official Title IX complaint against Nassar accusing him of violating the school’s sexual harassment policy.

In an investigative report prepared in response to her complaint, the school’s Title IX coordinator called Nassar’s methods a “liability” that exposed patients to unnecessary trauma. But that’s not what the school told Thomashow.

MSU ultimately sided with Nassar, concluding that his methods were medically appropriate. And, according to documents obtained by CNN, MSU gave Nassar and Thomashow different versions of that investigative report. Her version did not include the Title IX coordinator’s concerns.

The university maintains that no official there believed Nassar committed sexual abuse until newspapers began reporting on the allegations in the summer of 2016. Any suggestion that the university engaged in a coverup is “simply false,” a school statement asserted.

The former USA Gymnastics and Michigan State University doctor faces his third sentencing this week in Eaton County, Michigan. Now that an investigation is underway into how much MSU officials knew and when, Thomashow’s complaint is coming back into the spotlight.

Thomashow said she didn’t see Nassar’s version of the report until late 2017. She felt vindicated after trying for so long to reconcile the findings with what she knew in her gut really happened, she said.

“The investigation left me feeling so small, and worthless and disposable, that I never saw what I was doing as brave,” she said. “I felt embarrassed. I humiliated myself by even talking about it.”

Had she learned the full truth sooner, “I wouldn’t have felt like I misread things,” she said.

The incident

Thomashow grew up with Michigan State University in her blood. From the bedroom of her Lansing home she could hear the roar of football games from Spartan Stadium. She knew that one day she would go to school there, just like her mother.

In high school, Thomashow was an outgoing cheerleader. Pictures of her from that time show her smiling broadly from the top of human pyramids.

The cheerleading led to broken bones and pain that continued after she stopped. By 2014, she was 24 years old and had been suffering hip pain for years. She decided to seek treatment from the man described as the best sports medicine doctor in town – a doctor she had seen before, the same person her mother, a pediatrician, referred patients to. Her younger sister, Jessica, was a patient of his.

When she visited Nassar’s office on March 24, he had her lie down on a table. For the first hour she told investigators that he massaged her breasts and touched her vagina, according to the investigative report. He continued despite her repeated attempts to make him stop, she said.

“I had to literally stand up and push him off me,” Thomashow told CNN.

She was stunned as she put her clothes back on. She said he wouldn’t let her leave the room until she made a follow-up appointment, which she later canceled.

She knew something was wrong. But she worried that if she went to police they wouldn’t know how to handle it, she said.

“Something awful happened in that examination room … life had taught me enough to know that what happened was wrong,” Thomashow said. “After a lot of internal struggle, I knew that if I did not report it, I would not be able to sleep. If I didn’t say something and protect possible victims, I wouldn’t be OK with that.”

She went to another MSU doctor who elevated her complaint to the school’s Office for Inclusion and Intercultural Initiatives, according to the report.

Two weeks later, she got a call from Kristine Moore, assistant director of MSU’s Office of Institutional Equity. Their conversation prompted a Title IX investigation.

The investigation

Thomashow said she was nervous when she met with Moore and an MSU detective on May 29, 2014. At times, she said it felt like an interrogation. But she also got the impression that she was getting through to them.

On the same day, Det. Valerie O’Brien interviewed Nassar.

The accusations upset him, he told the interviewer, insisting he was not a “deviant.” He offered to perform the procedure on a volunteer officer.

“My wife, we didn’t even have sex until our honeymoon, that is the essence of who I am,” he told police.

He admitted to touching Thomashow as part of treatment, calling it something he did on a regular basis, according to the police report. He touted his credentials in treating the pelvic floor, which he described as overlooked area by most physicians. He said that he has been called “the body whisperer” for his expertise and indicated he has a Star Trek-themed slide in a PowerPoint presentation titled, “Pelvic Floor: Where no man has gone before.”

“I obviously did a poor job of explaining to the patient what I was doing,” he said in a follow-up email. “I know I did not do anything intentional but I obviously made her feel bad. I definitely have to completely change my treatment for sure.”

The next time Thomashow heard from Moore was in July, when she invited her to MSU to hear the investigation’s findings. When she heard the result of the investigation, Thomashow said she stormed out of the meeting.

“I could not believe that they were not taking me seriously,” Thomashow said.

Later, she received an email with the report, which contained statements from three physicians – all MSU staff – who called Nassar’s conduct “medically appropriate.”

The report called Nassar’s “failure to communicate” what he was doing “troubling,” but not a sexual harassment policy violation. The report Thomashow received ends with this three-line conclusion.

“We cannot find that the conduct was of a sexual nature. Thus, it did not violate the sexual harassment policy. However, we find the claim helpful in that it allows us to examine certain practices at the MSU Sports Medicine Clinic.”

Thomashow was struck by how short it was. But she tried to take heart in believing she had raised red flags.

“I remember reading over the like last paragraph of the conclusions and how short it was, and just being like, ‘Gosh, this is ridiculous, but at least they are going to put new safeguards in place.’ That’s what I just kept coming back to.”

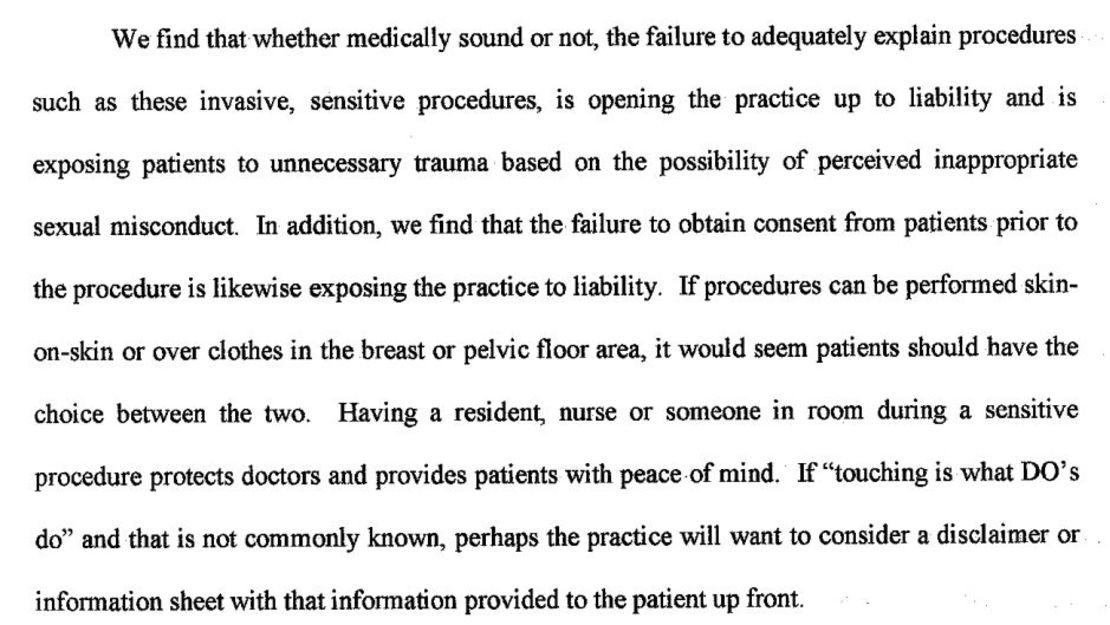

Unbeknownst to her, Nassar received a different version of the Title IX report. It was one page longer, and pointed out that, while the investigation couldn’t find that Nassar’s touching was sexual in nature, that “it would seem patients should have the choice” on whether or not they wanted procedures performed “skin-on-skin” or over clothes.

In the conclusion, Nassar’s version continues:

‘We find that whether medically sound or not, the failure to adequately explain procedures such as these invasive, sensitive procedures, is opening the practice up to liability and is exposing patients to unnecessary trauma based on the possibility of perceived sexual misconduct. In addition, we find that the failure to obtain consent from patients prior to the procedure is likewise exposing the practice to liability.”

The truth comes out

Years went by. Thomashow wanted to believe that what the report said was true and that she had not been sexually assaulted. She kept going back over the details of that appointment in her head. The way she’d say, “No,” and the way he would tell her he was almost done.

It wasn’t until late 2017 that Thomashow saw Nassar’s version of the report.

“It’s just another sign of how they mishandled, how they completely botched my investigation,” Thomashow said.

MSU did not respond to requests for comment.

Licensed therapist and MSU alum Lauren Allswede said she was surprised to learn that the university sent Thomashow and Nassar different versions of the report. While working for the university’s sexual assault program, she said she dealt with multiple Title IX investigations.

“They make a big deal about everybody getting the same information at the same time,” Allswede said.

In her experience, she said it was common for the university to blind copy a victim and perpetrator on the same email to protect their privacy, but also to make sure they got the same information at the same time.

Over seven years, Allswede says she saw hundreds of cases of sexual assault involving students. Only one was ever prosecuted, she said. She eventually left the university in 2015.

“There was a long time where I was at the university, where I felt like I could really help people and even help people navigate when they felt like they had been wronged by the university,” Allswede said. “Over the years, I felt like I was just helping people respond to how the university had hurt them.”

Police sent their findings to the Ingham County Prosecutor’s Office, which declined to bring charges in 2015. In a statement included in emails between campus police officers, Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Steve Kwasnik said it appeared that Nassar was doing “a very innovative and helpful manipulation of ligament.”

“He needs to do a much better job of explaining what he is doing to the patient who rightfully might feel violated by his technique.”

One year later, Nassar was arrested on federal child pornography charges.

MSU denies knowing about Nassar

After Thomashow’s investigation, MSU entered into an resolution agreement in 2015 with the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights over its handling of sexual assault complaints from two students. Before signing the agreement, the Education Department didn’t know about the Nassar allegations, according to documents obtained by CNN.

As part of the agreement, the school was required to report sexual assault allegations to the DOE, including those that preceded the agreement. But MSU did not share Thomashow’s report with the DOE, according to documents obtained by CNN.

MSU deputy general counsel Kristine Zayko asked the Department of Education in October 2017 to end its monitoring, citing changes to Title IX guidance. The department refused, based in part on the Nassar case.

In a December 6 letter from MSU’s hired, external counsel, Patrick Fitzgerald, told Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette that the university will cooperate with its independent investigation. In the same letter, Fitzgerald said, “we believe the evidence will show that no MSU official believed that Nassar committed sexual abuse prior to newspaper reports in late summer 2016.”

For Thomashow, their response further confirms her feeling that the university’s focus wasn’t on protecting her in the investigation, but their own staffer, Nassar.

“I think that the way that my investigation was handled was not in a way to bring out the truth, but instead it was performed in a way to conceal and protect a pedophile,” Thomashow said.

With Nassar guaranteed to spend the rest of his life in prison, Thomashow doesn’t want to focus on him anymore. She wants to move forward and focus on learning to trust herself and others again, with the help of her therapy dog, Olive.

“For all of the anxieties that I experience now I also know that even though I continue to question myself, that I need to stick with my intuition, and I need to continue to speak up if I see something wrong happens,” Thomashow said. “I need to just hold firm to my belief that you do what is right, even if it’s not what’s easy.”

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to correctly describe the sibling relationship between Amanda and Jessica Thomashow. A photo caption has also been updated to accurately describe where Amanda Tomashow was speaking.

Jean Casarez, Sonia Moghe and Linh Tran reported from East Lansing. Emanuella Grinberg wrote this story in Atlanta.