All around the Lebanese capital of Beirut, posters of Prime Minister Saad Hariri have gone up proclaiming “Kulna ma’ak” – “We are all with you.” They don’t seem to be an endorsement of Hariri as a politician; rather, they appear to be an expression of solidarity with man whom the Lebanese believe is in “captivity” in Saudi Arabia. It’s a rare moment in Lebanon when country comes before sect.

On Sunday night, when Hariri went on Lebanese television for the first time to explain his sudden resignation a week earlier, he looked exhausted. “I wanted to make a positive shock for the Lebanese people so the people know how dangerous the situation we are in,” he said.

Indeed, his resignation, made via the Saudi-funded news channel Al-Arabiya from the Saudi capital, Riyadh, was a shock. Nothing like that had ever happened before. He accused Iran and its Lebanese ally, Hezbollah, of destabilizing his country and the region. He claimed there was a threat against his life.

But some in Lebanon, including the widely-supported President, have indicated they believe there was a different explanation – that Saudi Arabia was somehow behind Hariri’s resignation, irritated that he hadn’t done more to stand up to Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed faction that shares power in Lebanon.

Saudi Arabia firmly denies the claim. But if Hariri’s former backers in Riyadh hoped that his removal would prompt a groundswell against Hezbollah, or its allies in Riyadh’s longtime Gulf rival Iran, they would have been disappointed. No such groundswell emerged.

Beyond the shock of his announcement, in Lebanon there was a shrug and a sigh of weariness that the country has once more been thrown into crisis.

The day after Hariri’s resignation, Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah appeared on Al-Manar, Hezbollah’s TV station, and calmly suggested Hariri was not a free man, that Saudi Arabia dictated his resignation statement. Nasrallah didn’t attack Hariri, but rather expressed sympathy for the 47-year-old former prime minister.

And it wasn’t just Nasrallah. On Wednesday, Lebanese President Michel Aoun told journalists Hariri was a “hostage” in Saudi Arabia. His detention, said Aoun, “is an attack on us, and it’s an attack on our independence.” Lebanese don’t agree on much, but it is hard to find anyone who believes Hariri is the master of his own destiny.

Even Saudi-aligned politicians from Hariri’s own party seemed to rebuke their political patrons, calling for Hariri’s return for “the dignity of the nation.” Responding to rumors that Saudi Arabia had a new pick for Lebanon’s Prime Minister, Interior Minister Nouhad al-Machnouk, also Saudi-backed, quipped: “We are not a herd of sheep or a piece of property to hand over from one person to another.”

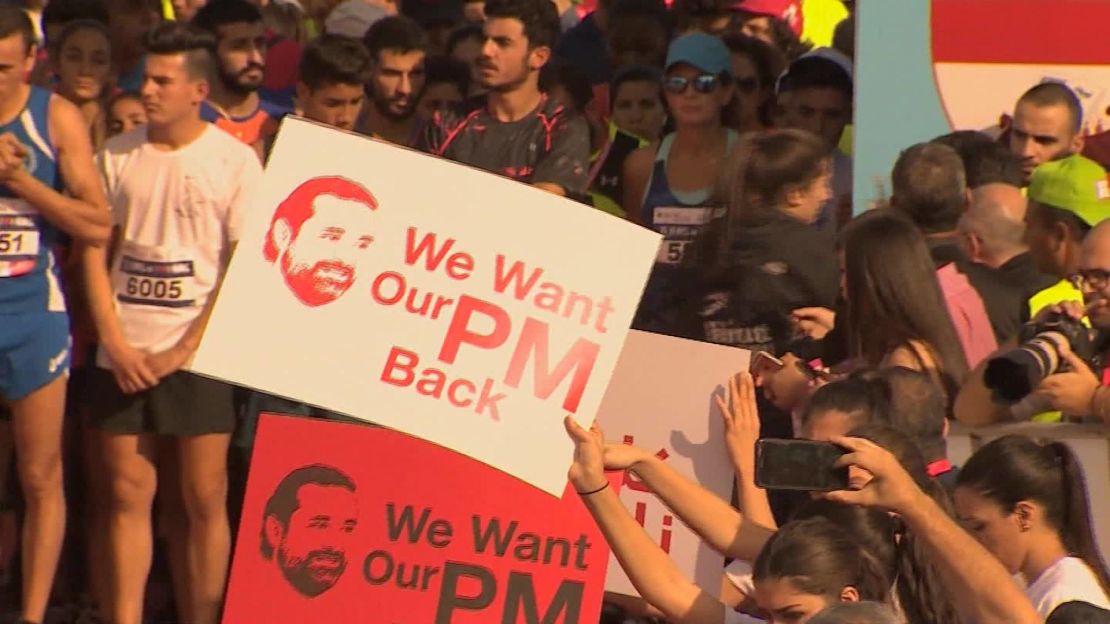

In Beirut, residents express similar views. “We want our prime minister back,” Amin, a man from south Lebanon who had come to participate in last Sunday’s Beirut marathon told me. “He represents all of us.”

“In the end, he’s Lebanese, and the Lebanese are all brothers, regardless of their sect,” said another runner, Alin. She declined to say she is a Hariri supporter.

Lebanon is a small, resource-poor country that has long depended on oil-rich countries like Saudi Arabia for jobs and business opportunities. Hundreds of thousands of Lebanese work in the Gulf, sending back billions of dollars a year in remittances that help keep the economy afloat. For decades Lebanon has been a favourite playground for wealthy Saudis and others who come here to indulge in the alcohol and carnal pleasures strictly forbidden in their arch-conservative lands. It’s a relationship of dependency coloured by more than a tinge of resentment.

In his only television interview, and subsequently on Twitter, Hariri promised he would return “soon,” “in two or three days,” “in two days.” But it didn’t come to pass. On Saturday morning he arrived in Paris to meet with President Emmanuel Macron.

Shortly after Hariri’s arrival, Lebanese President Michel Aoun tweeted that he had spoken with Hariri, who told him he would be back in Beirut to attend Lebanon’s Independence Day celebrations, which take place on Wednesday. Hariri, suddenly communicative once more, spoke by phone with a variety of Lebanese leaders and politicians from Paris.

Throughout the two weeks Hariri was in Riyadh, Saudi officials were at pains to stress that Hariri was not a hostage, but the drama of the resigned prime minister’s status has touched a raw nerve.

In his only television interview, and subsequently on Twitter, Hariri promised he would return “soon,” “in two or three days,” “in two days.” But he hasn’t. Now he has accepted an invitation from French President Emmanuel Macron to come with his family to Paris Saturday. Afterwards, Lebanese officials told me, they believe he will eventually return to Beirut. “In sha Allah,” – God willing – they are quick to add.

Saudi officials are at pains to stress that Hariri is not a hostage, but the drama of the resigned prime minister’s status has touched a raw nerve.

Shortly after Hariri resigned, Saudi Minister for Gulf Affairs Thamer Sabhan warned the Lebanese they have to choose “either peace, or to live within the political fold of Hezbollah.”

“Whether you like them or not, you can’t remove Hezbollah from Lebanese politics or society,” Bahaa, a young man told me off Hamra Street.

While many here complain about Hezbollah’s powerful military wing, and their perceived loyalty to Iran, there is little appetite for a showdown with the group, which would almost certainly lead to an armed confrontation, or another civil war.

The Lebanese are accustomed to foreign interference, “going back to the Pharaohs and the Romans,” political satirist Abdal Rahim Al-Awji told me at the venerable west Beirut Café Younes. Today, “it’s not just the Saudis,” he said. “It’s everybody, like the Iranians, the Americans. Everybody!”

This time, however, many feel interference has gone to an entirely new level. It’s one thing for an outside power to pressure or cajole, bribe or blackmail Lebanese politicians, but another thing altogether to detain the prime minister, the Lebanese say.

If Saudis are indeed behind the machinations, they may find they have waded a bit too deep into Lebanese politics this time. There’s an old saying about this country, that it’s easy to swallow, but hard to digest. Saudi Arabia, led by impetuous 32-year-old Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, may be in for a bout of Lebanese indigestion.