Story highlights

NEW: Generators are arriving to shore up the city's ability to power drainage pumps

NEW: The power turbine that broke this week could be back online soon, mayor says

Louisiana’s governor has declared a state of emergency in New Orleans as officials and residents scrambled in the aftermath of last Saturday’s heavy storm that left hundreds of homes and businesses flooded.

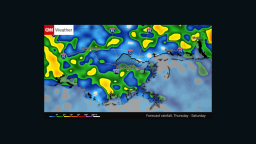

With more rain in the forecast, New Orleans leaders rushed to deal with a series of malfunctions in the city’s drainage system – and to face a critical public after some local officials waited days to reveal the full extent of system failures.

“There is no need for panic,” Mayor Mitch Landrieu said during a Friday news conference while advising residents to remain vigilant and to stay off the streets if rain starts to fall.

The city has struggled with its unique drainage system for years. Century-old pumps are in constant need of repair, catch basins repeatedly clog, and potholes and sinkholes form seemingly everywhere.

Because of New Orleans’ unusual topography – with many areas below sea level and protected by levees – pumps in every neighborhood must suck rainwater out of storm drains and canals and push it into a nearby lake or other water bodies. In most other places, gravity does that work.

This time, unlike during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, a huge amount of rain falling in a very short period of time caused the flooding. The rain tested the drainage system – not the chain of levees, flood walls and pumps that the federal government built after Katrina.

Here’s what the recent flooding looks like by the numbers:

10 inches of rain

Within three to four hours on Saturday, as much as 8 to 10 inches of rain fell across New Orleans.

“The rate of rainfall in many neighborhoods of the city was one of the highest recorded in recent history,” the city said in a news release.

The storms caused widespread street flooding, damaging “a couple hundred” properties,” city officials said, contrasting the figure to more than 200,000 properties ruined in Katina.

The storms caused a 100-year flood, meaning there’s usually only a 1% chance that a flood of such magnitude could happen in any given year, the National Weather Service determined.

“There is no drainage system in the world that can handle that immediately,” outgoing Sewerage & Water Board Executive Director Cedric Grant told CNN affiliate WDSU.

The drainage pumps can process 1 inch of rain in the first hour of a heavy storm, then a 1/2 inch in each subsequent hour, Grant said.

Indeed, it took “approximately 14 hours to completely drain the city,” Grant reported Thursday to the water board.

16 drainage pumps out of service

New Orleans uses 120 pumps spread across every neighborhood to suck water out of storm drains and canals and push it out of the levee-enclosed city.

About 100 of those pumps are huge – some as big as a garage – and are key to draining rainwater; the rest are small and constantly working to clear the streets of runoff from lawn-watering and other daily water usage.

Sixteen pumps were out of service over the weekend, making things even worse for a drainage system that already was working above its capacity, and streets began flooding. Six of those pumps were big ones located in neighborhoods that got the most rain; three others were big ones elsewhere in the city. The other seven were the smaller, constant-duty pumps.

4 of 5 power turbines out of service

The problems continued piling up for New Orleanians throughout the week.

A small control-panel fire late Wednesday took out one of four turbines that power the city’s oldest, strongest pumps, the mayor said. The other three turbines had been offline for weeks or months for repairs. A fifth turbine has been pressed into action to operate the oldest pumps, but only 38 of the 58 available pumps can be run at one time, city officials have said.

It all means the drainage capacity in the oldest part of the city, including the French Quarter, essentially has been cut in half. (Pumps in the newer parts of New Orleans largely run on commercial or diesel power and are chugging along, though a few are out of service for routine repairs.)

City officials late Thursday began testing repairs to the turbine that broke the previous night, the city said in a news release.

“The repair has been successful as of last night,” Landrieu said Friday, adding that electricians were “low-loading” the turbine to test it before putting in back into use, perhaps within a matter of hours.

26 generators on the way

Meantime, six of 26 generators that officials ordered in light of the system failures had arrived, though it could take several more days to configure and install them, the mayor said. A dozen more generators were due to arrive Friday, with the final eight arriving Sunday, he said.

The generators “will stay with us through hurricane season, even after those two turbines get back online,” Landrieu said, adding that even when they’re in place, “there will continue to be some risk” and the system will still not be “what we need in the event of a deluge or a major rain event.”

With the city’s pumping capacity weakened and a new round of severe weather threatening, Gov. John Bel Edwards on Thursday declared a state of emergency, and some city schools closed Friday for a second day.

Sandbags will be available Friday afternoon for property owners who want to block rising water, Landrieu said, and police have stationed barricades or high-water vehicles at 20 low spots around town to prevent people from venturing into floodwaters and helping those who might.

$2 billion repairs

Ten years after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, New Orleans in 2015 was awarded $2 billion in grants to fix roads and infrastructure by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. A portion of that money is earmarked for drainage system repairs, CNN affiliate WGNO reported.

Landrieu said this week that those repairs and improvements are still ongoing – adding that the federal money is just a fraction of the $9 billion experts say is needed to update the system.

“We have an old system that needs to be upgraded,” Landrieu said Friday. “This is really what the infrastructure funding in the United States of America is about, not just for our drainage system but for any system in America,” including “roads, bridges and those kinds of things.”

The pumps that drain rainwater from New Orleans’ streets are not the same pumps that the US Army Corps of Engineers built after Katrina as part of a $14 billion effort to fortify the city against tropical events.

4 city officials asked to resign

Landrieu, who as mayor serves as president of the Sewerage & Water Board, requested the resignations of four top officials, including the director and the top engineer at the municipal water utility, amid confusion over why water lingered for hours after Saturday’s deluge.

City leaders at first said the drainage system was “operating at its maximum capabilities,” CNN affiliate WDSU reported. Days later, some of the same officials admitted key pumps that serve flooded neighborhoods had been out of service.

“I completely and totally understand and feel the people’s frustration after the flood, and more importantly some of the misinformation that they have been given,” Landrieu said at a news conference earlier this week.

Water utility employees and the director of the city’s Public Works Department will leave their jobs in the coming weeks and months, a city spokesperson said. Two Sewerage & Water Board members also have resigned, the mayor said, with one of those officials reportedly slamming Landrieu for scapegoating the water utility.

The number of pumps available during Saturday’s storm has been updated based on new information provided by city officials.