Story highlights

NOAA predicts the Atlantic will see 14 to 19 named tropical systems this year, an increase over its last estimate

Forecaster: "We're now entering the peak of the season when the bulk of the storms usually form"

Unseasonably warm ocean temperatures and a no-show from El Niño will contribute to what may be the busiest Atlantic hurricane season in seven years, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced on Wednesday.

NOAA estimates the ocean will see 14 to 19 named tropical systems this year, up from the 11-17 they had predicted in a previous outlook released in May.

“The season has the potential to be extremely active, and could be the most active since 2010,” NOAA said on Wednesday.

The 2017 hurricane season officially began June 1 and ends November 30.

Though NOAA’s outlook still calls for 5 to 9 hurricanes, the latest update increases the number of likely major hurricanes by one, to 5.

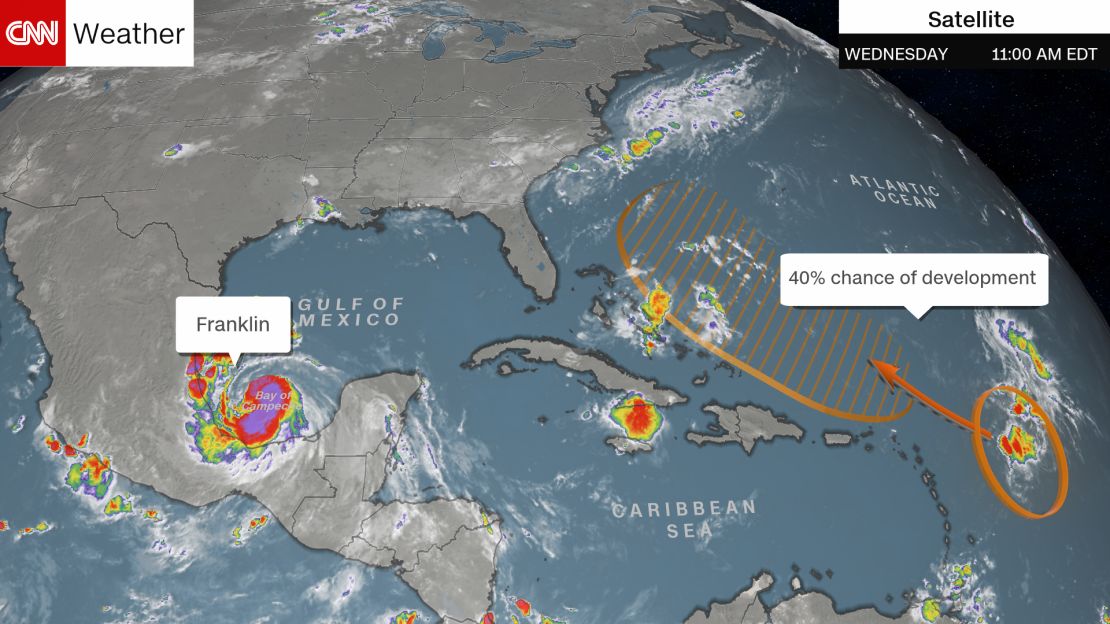

Hurricane Franklin, located in the southern Gulf of Mexico’s Bay of Campeche, is the season’s first hurricane and will move into Mexico early on Thursday.

NOAA’s upgraded outlook agrees with last week’s update from Colorado State University.

CSU predicts 16 named storms – including the five that have already occurred – with eight becoming hurricanes and three reaching major hurricane status (winds above 111 mph).

Peak season

“This season has had a running start,” according to Ben Friedman, acting NOAA administrator. Tropical Storm Arlene formed briefly in April in the north-central Atlantic. An extremely rare occurrence, Arlene was just the second named storm on record for the month of April.

Since then the season has remained above average with respect to the number of storms, with six named storms by August 6. On average, the sixth named storm does not occur for another month, around September 8.

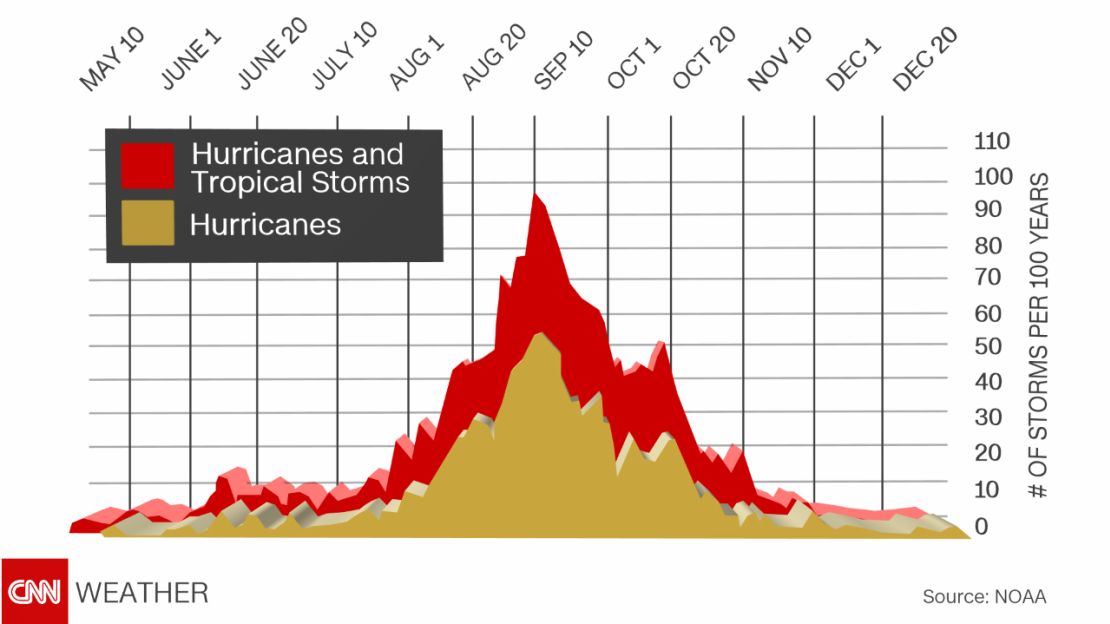

Even though the calendar says we are over one-third of the way through the hurricane season, we are just getting into its busiest part. In fact, over 75% of the named storms come during the peak months of August, September, and October.

“We’re now entering the peak of the season when the bulk of the storms usually form,” said Gerry Bell, lead seasonal hurricane forecaster at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

“The wind and air patterns in the area of the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean, where many storms develop, are very conducive to an above-normal season,” Bell said.

As if on cue, the tropical Atlantic has been heating up this week, with Franklin churning in the southern Gulf of Mexico and another area of potential development farther out in the ocean.

Franklin has already prompted hurricane warnings for parts of Mexico’s east coast as the system will move into the Mexican state of Veracruz late Wednesday into early Thursday.

Several hundred miles to the east, a disorganized cluster of storms bears watching as it moves towards near the Lesser Antilles.

The National Hurricane Center currently gives the system a 40% chance of developing, and forecast models show it could approach the eastern United States coastline later this weekend. It is still too early to say for sure if the system, which would be named Gert if it develops, would curve back out to sea before reaching the US coast.

The El Niño effect

Forecasts made earlier this year were predicting “slightly below-average activity.” These forecast were made in April and May, when a weak to moderate El Niño was forecast to develop during the peak of hurricane season.

“The chance of an El Niño forming, which tends to prevent storms from strengthening, has dropped significantly from May,” Bell said.

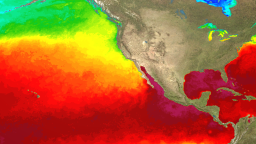

El Niño is a naturally occurring phenomenon characterized by warmer than normal water in the eastern Pacific equatorial region. While El Niño occurs in the Pacific Ocean, it has widespread impact on the global climate. One of its effects is increased wind shear across the tropical Atlantic, which creates hostile conditions for tropical storm development.

With a lack of El Niño taking shape, Colorado State forecasters say there’s a 62% chance of a major hurricane making landfall in the United States this season. The average risk is 52%.

Due for a major hurricane?

Amazingly, the US has not experienced landfall of a major hurricane – a Category 3 or higher, with sustained winds of 111 mpg and higher – since Hurricane Wilma in 2005.

“The odds of going 11 years without a major hurricane landfall in the US is around 1 in 2,000,” said Phil Klotzbach, a hurricane research scientist at Colorado State University.

“Roughly 25% of major hurricanes that form in the Atlantic make a US landfall,” he added. “We have had 31 major hurricanes since Wilma in 2005. The odds of having 31 major hurricanes form in the Atlantic with zero landfalls would be around 1 in 7,500.”

That streak nearly ended last year with Hurricane Matthew.

After several quieter seasons, 2016 was above normal, as expected, with 15 named storms, seven hurricanes and four major hurricanes. Hurricane Matthew had the greatest impact, with its center passing just offshore of eastern Florida and Georgia as a major hurricane before making landfall in South Carolina as a Category 1 storm and bringing historic flooding to North Carolina.

Join the conversation

There was also Hurricane Hermine, which became the first hurricane to make landfall in Florida in 11 years, the state’s longest hurricane-free streak.

“There is a potential for a lot of Atlantic storm activity this year. We cannot stop hurricanes, but again, we can prepare for them,” said Friedman.

CNN Meteorologist’s Taylor Ward and Judson Jones contributed to this report.