Today, we know that smoking kills. But it wasn't so long ago that images of doctors, nurses and celebrities told us to light up. It was good for you, they said. These historical ads tell the story.

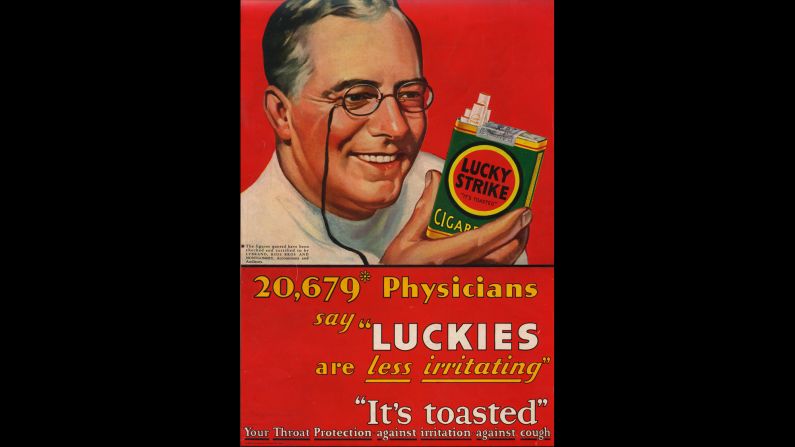

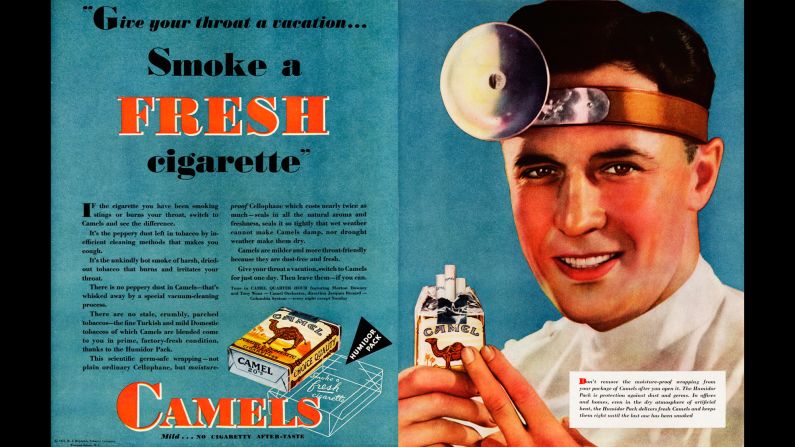

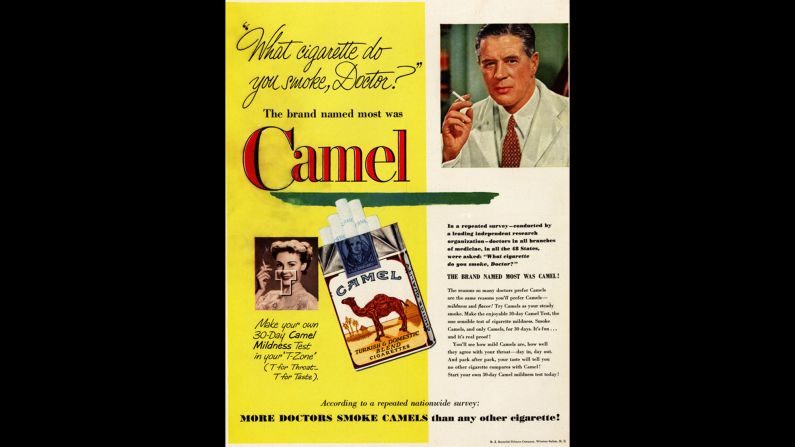

Tobacco advertisers often used the depiction of an ear, nose and throat doctor to promote cigarettes. "People in those days didn't know about lung cancer, but they knew that it was rough on your throat," said Dr. Robert Jackler, founder of the research group SRITA, or Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising, which documents the history of tobacco advertising. "They knew smoking irritates and makes you cough and gag. So having a throat doctor tell you it's OK to smoke was key to success in tobacco advertising and sales."

By today's standards, the ads were shocking. In one ad, a "doctor" describes how a little girl could live to 100 -- years longer than her mother -- while promoting the virtues of smoking.

"The none-too-subtle message was that if the doctor, with all of his expertise, chose to smoke a particular brand, then it must be safe," SRITA said. Tobacco ads using images of health professionals like doctors, nurses and dentists ran from about 1935 through the early '60s.

"The none-too-subtle message was that if the doctor, with all of his expertise, chose to smoke a particular brand, then it must be safe," SRITA said. Tobacco ads using images of health professionals like doctors, nurses and dentists ran from about 1935 through the early '60s.

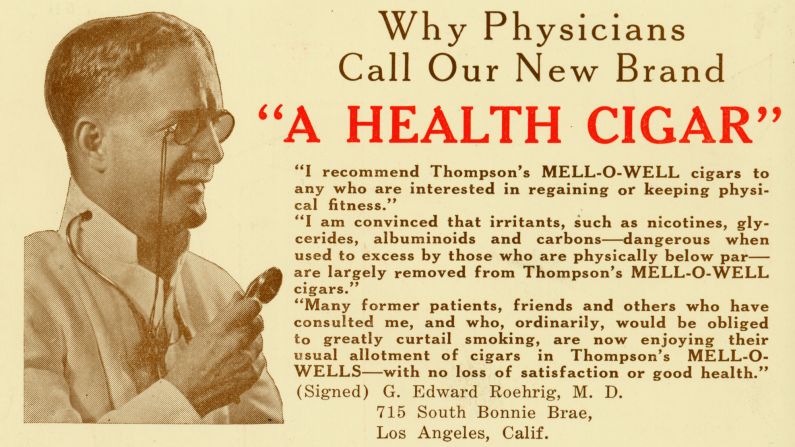

Look closely at these ads. You won't see a doctor's name. That's because all of the doctors were really actors. Advertising by real doctors was frowned on as unethical, SRITA says. "Unlike with celebrity and athlete endorsers, the doctors depicted were never specific individuals, because physicians who engaged in advertising would risk losing their license."

This ad was a rare exception. Dr. G. Edward Roehrig was indeed a real doctor, practicing initially in Chicago and later in Los Angeles. "Ironically, he died of lung cancer," Jackler said.

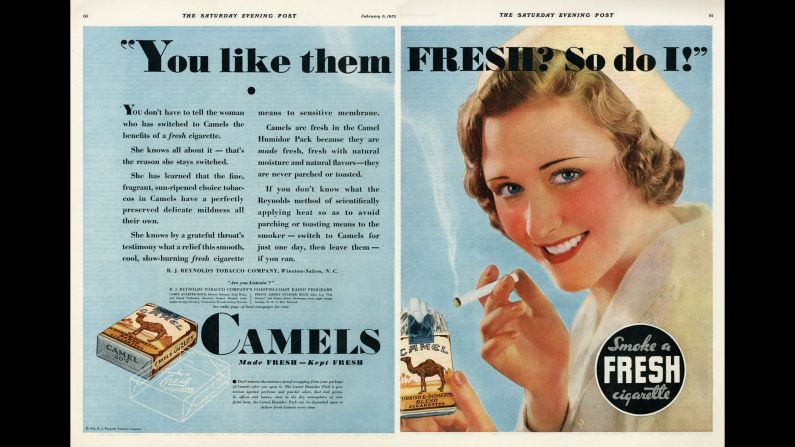

In the early 1900s, women began picking up smoking habits -- and consequently, nurses were used to promote the benefits of particular cigarettes. That would soon become common in the world of tobacco advertising. This ad for Camel cigarettes was released in 1932.

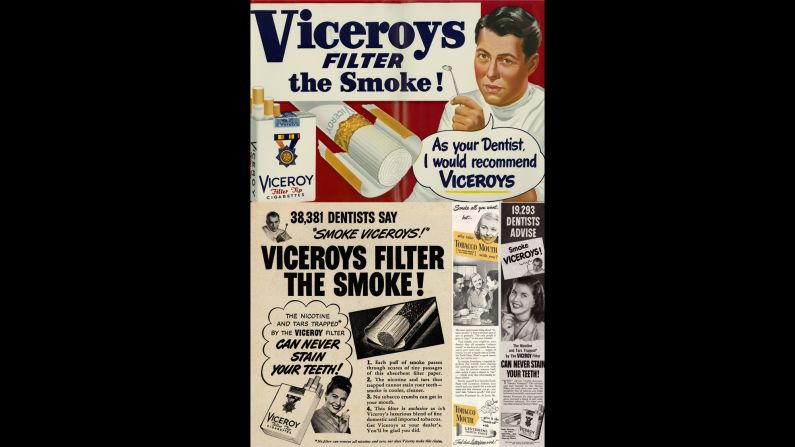

In this campaign, Viceroys attempted to assure the public that its brand wouldn't stain teeth, giving the claim credibility by using an actor posing as a dentist.

The use of celebrities, such as this ad with TV legend Ed Sullivan, was another common tactic to earn the public's trust. Here, Sullivan says he has smoked the Chesterfield brand for 22 years.

Ad copy then offers some medical support: "A medical specialist is making regular bi-monthly examinations of a group of people from various walks of life. ... No adverse effects on the nose, throat, and sinuses of the group smoking Chesterfields."

Ad copy then offers some medical support: "A medical specialist is making regular bi-monthly examinations of a group of people from various walks of life. ... No adverse effects on the nose, throat, and sinuses of the group smoking Chesterfields."

The use of sports celebrities was also common in the early days of tobacco advertising. Here, leading names in rodeo, polo, table tennis and fishing are placed above yet another endorsement by doctors.

"Little protest was heard from the medical community or organized medicine," SRITA said, "perhaps because the images showed the profession in a highly favorable light."

The American Medical Association did not respond to a request for comment.

"Little protest was heard from the medical community or organized medicine," SRITA said, "perhaps because the images showed the profession in a highly favorable light."

The American Medical Association did not respond to a request for comment.

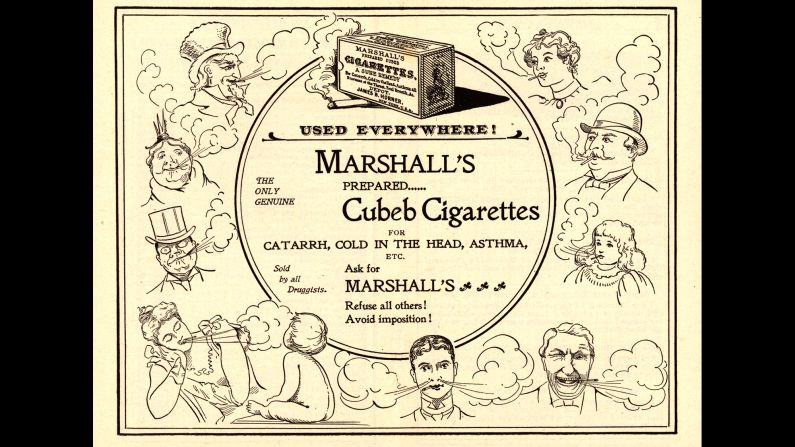

Some cigarette companies were bold enough to state health benefits on their ads. Here, Marshall's Cubeb cigarettes claim to be a "sure remedy" for asthma, nasal congestion and the common cold.

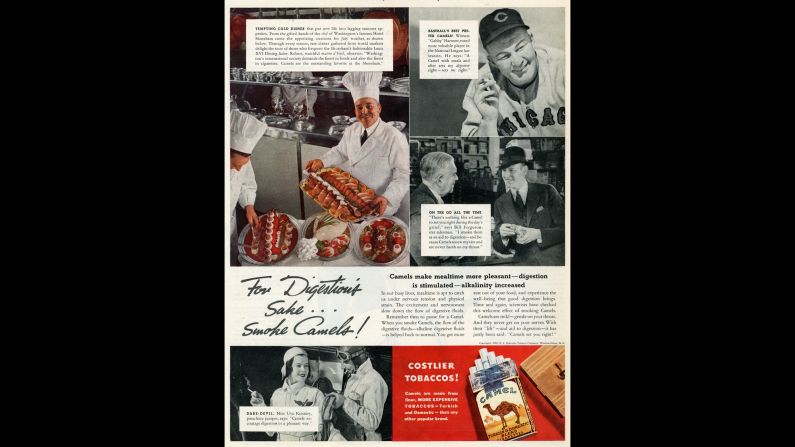

Another series of ads claimed that smoking improved digestion. In this mid-1930s campaign, Camel said, "Using sensitive scientific apparatus, it is possible to measure accurately the increase in digestive fluids ... that follows the enjoyment of Camel's costlier tobaccos. The same studies demonstrate that an abundant flow of digestive fluids is important also to the enjoyment of food."

This ad claims that the longer length of the cigarette reduces health dangers since it would take more time for the smoke to reach the smoker's lungs, allowing more filtering of toxins.

"In 1950, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) investigators had decided that king-size cigarettes, like Embassy, contained 'more tobacco and therefore more harmful substances' than are found in an ordinary cigarette," SRITA said.

"In 1950, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) investigators had decided that king-size cigarettes, like Embassy, contained 'more tobacco and therefore more harmful substances' than are found in an ordinary cigarette," SRITA said.

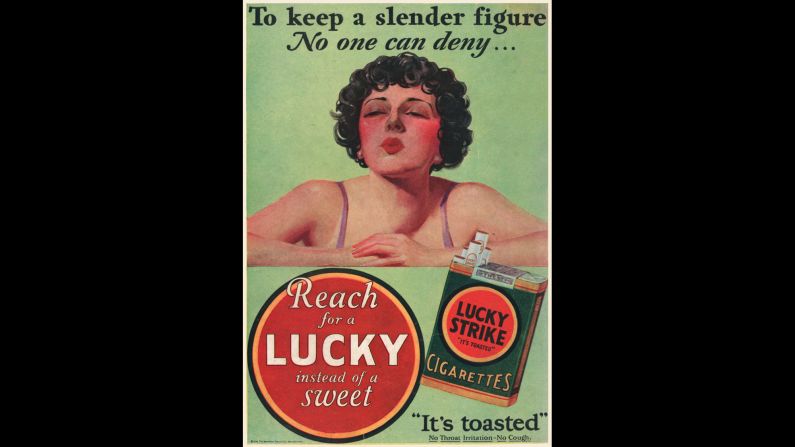

Tobacco companies also capitalized on smoking's tendency to reduce appetite. Many ads promoted the use of cigarettes as a tool for weight loss. Women were a prime target.

Advertisements aimed at men often insinuated that weight loss from smoking would lead to greater athletic ability, while assuring the public that over 20,000 physicians found Lucky Strike cigarettes to be easier on the throat because they were "toasted."

"All American grown tobacco was toasted, flue cured, and that's what made American cigarettes milder than European cigarettes," says SRITA's Jackler. "Toasting leaves made a very soft smoke you could draw into your lungs."

"All American grown tobacco was toasted, flue cured, and that's what made American cigarettes milder than European cigarettes," says SRITA's Jackler. "Toasting leaves made a very soft smoke you could draw into your lungs."

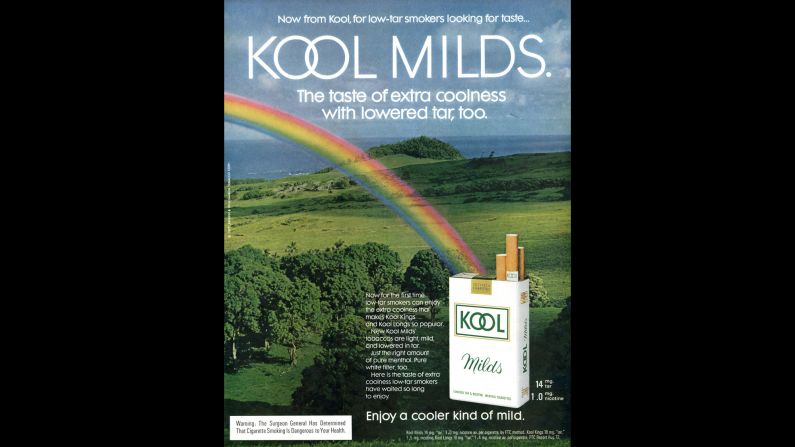

Using images of health professionals to win the trust of the public and downplay the growing concern over smoking continued until the early '60s. In 1965, the Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act was passed; it was updated in 1969 to read as it does in this ad: "Warning: The Surgeon General Has Determined that Cigarette Smoking Is Dangerous to Your Health."

CNN reached out to major tobacco companies for comment about their ad campaigns during this era. Only R.J. Reynolds, maker of Newport, Camel and Pall Mall, replied. "I am not in a position to provide any insights or comments on advertisements that are more than 70 years old," said David Howard, Reynolds American Services senior director of communications.

CNN reached out to major tobacco companies for comment about their ad campaigns during this era. Only R.J. Reynolds, maker of Newport, Camel and Pall Mall, replied. "I am not in a position to provide any insights or comments on advertisements that are more than 70 years old," said David Howard, Reynolds American Services senior director of communications.