Story highlights

Barcelona celebrating 25th anniversary of first European Cup win

1992 Wembley win created a lasting legacy

Club has now won five European Cups

There was a time when Barcelona fans did not expect success. To wallow in pessimism was the accepted norm. Trophies? Titles? They were for others, usually the reserve of the grandiose club of the capital, Real Madrid.

The European Cup was as elusive as the unicorn: talked about, looked at with wonder, pictured with others but never seen in this Catalonian city by the Mediterranean sea.

A club like Barcelona, the nihilistic fans would say, would never reach the zenith of European club football. There was no bombast, no peacocking, just fatalism.

The ironhanded years of General Francisco Franco, whose dictatorial regime had crushed Catalonia’s earlier limited autonomy, had ruined the spirit.

True, Barcelona had been able to sign football greats such as Johan Cruyff and Diego Maradona, but two European Cup finals – in 1961 and 1986 – had ended in defeat and between 1961 and 1990, the club won just two league titles in Spain’s top flight, finishing runners up 13 times.

But all changed on May 20, 1992.

That was the day Barcelona won its first European Cup. That was the day the club, its city, and football was transformed.

Barcelona’s ‘Holy Grail’

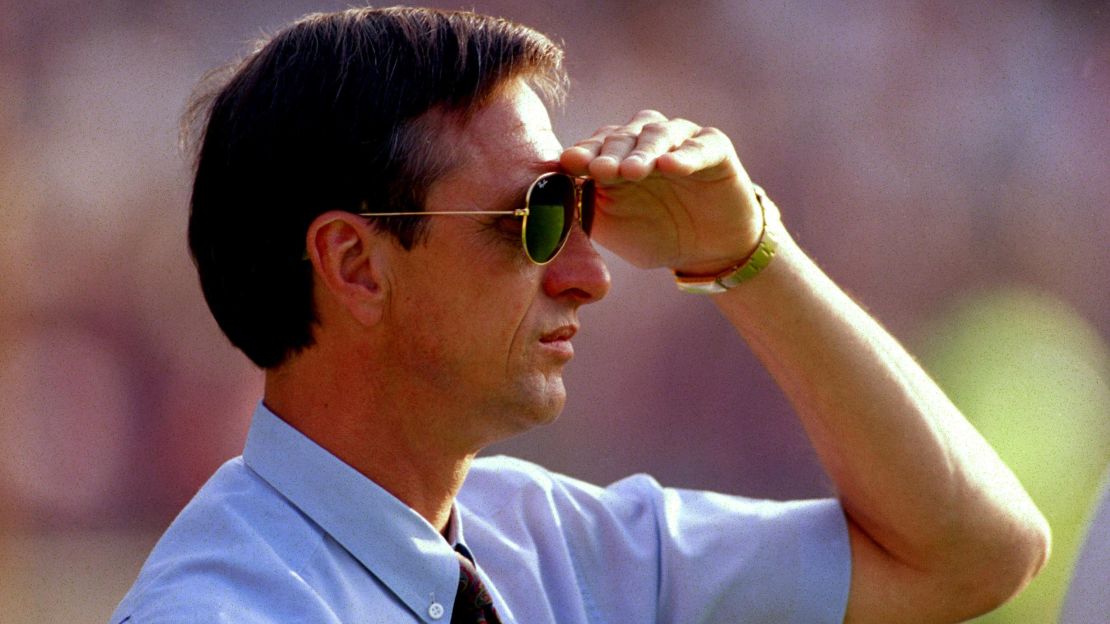

Springtime in London. Cruyff, the football revolutionary, now Barcelona’s visionary coach, and his assembled team of artists, known as the “Dream Team,” are at Wembley for the first European Cup final of the Dutchman’s managerial reign.

Opponents Sampdoria have poachers supreme in Gianluca Vialli and Roberto Mancini, but Barcelona can offset the Italians with Michael Laudrup, Pep Guardiola, Hirsto Stoichkov and Ronald Koeman.

If it’s a title-winning team of regal talent, Barcelona’s fans, however, are preparing for the worst.

Memories of the club’s European Cup final defeat on penalties to Steaua Bucharest in 1986 are still fresh so supporters ask Cruyff to record a few soothing words for the return journey to Spain, a precaution should the worst happen.

But Cruyff, in his fourth year as Barca manager, wants his players to forget about the club’s past. His battle cry as he sends his men out onto the Wembley turf? “Go out there and enjoy it.”

“The European Cup was the football holy grail for Barcelona,” Graham Hunter – author of “Barca, the making of the greatest team in the world” – tells CNN.

“It was more than a thorn in their side. It was something that was almost mythical, to get to that final and win it.”

Full-time turns into extra-time and the score remains goalless. Knees are knocking, in the stands and in the dugout. Penalties are looming. Fear.

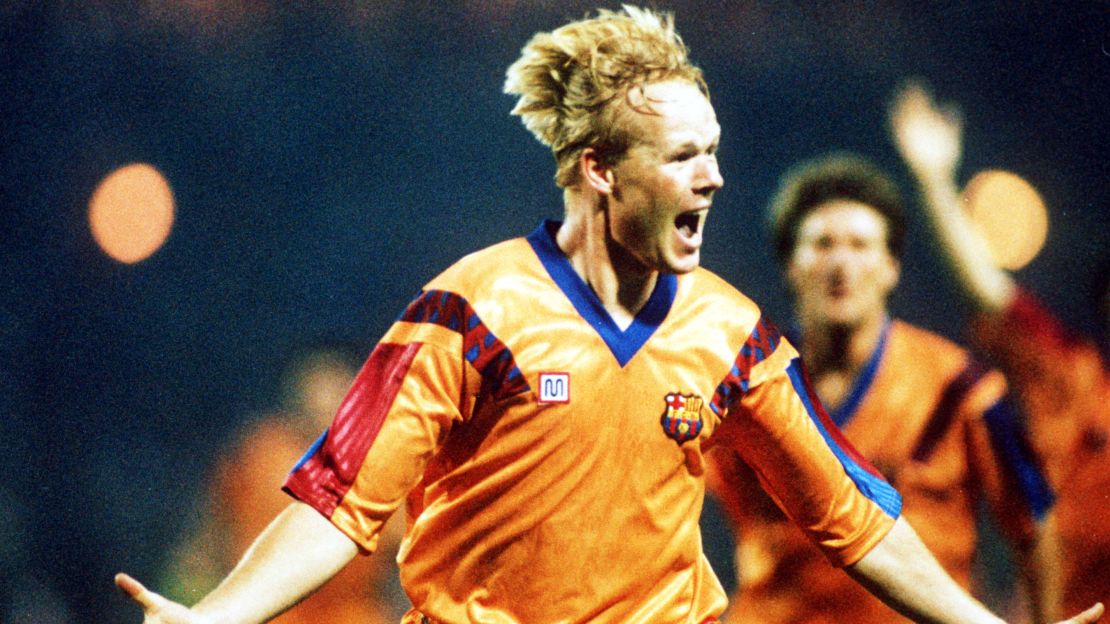

But with less than 10 minutes remaining Barcelona is awarded a free-kick. Koeman, the sweeper with a sniper’s eye for long-range goals, steps forward.

Watching on television in Barcelona is a teenaged Xavi, an academy player who would go on to become one of the club’s greats.

“It was truly an extraordinary experience,” the former Spain and Barcelona midfielder tells CNN as he remembers the match unfolding.

Twenty-five yards from goal, Koeman shoots. He aims low towards the bottom corner. Defenders rush forwards, breaking from the defensive wall. The goalkeeper stretches and dives to his right. But they’re all too late. They are beaten.

The goalscorer sprints towards the sidelines and his teammates follow, swallowing him up in a jubilant wave of orange shirts when he is caught.

When the blond Dutchman emerges from the celebratory mass, he is hiding his face in his hands, using his fingertips to hold back tears.

His is the winning goal, a strike which unshackles his club from the heavy weight of history. “It was the beginning of big changes,” Koeman, who pulled on Barca’s blue and garnet shirt over his orange top before lifting the European Cup, would later say.

The genius from Amsterdam

Cruyff had made an impact at the Camp Nou as a player, winning the title in his first season following a world-record move in 1973, but it was the Dutchman’s appointment as coach in 1988 that changed the club’s DNA.

On May 4, when Cruyff is announced as Barcelona’s coach, the team is experiencing its worst season since 1941-42. The club is in debt and in crisis. They go on to finish sixth in the league, two points off 10th place, while Real Madrid celebrate a fifth straight La Liga title. Ignominy.

He had, Cruyff said, inherited players who “wanted to have fights about the past.”

In planning for the future a manic period of departures and arrivals follows – 15 players are sold and 12 are bought. Cruyff, one of the greatest players of all time, took risks but rewards followed.

Among the newcomers are the young and eager Txiki Begiristain, Jose Mari Bakero, Julio Salinas and Eusebio Sacristan, a quartet which would become crucial cogs in the manager’s Dream Team.

“They were conditioned to coming second,” says Hunter of the Barcelona squad Cruyff inherited.

“He felt there was a losing mentality around Catalonia itself and that this was a product of years of oppression under the Franco dictatorship. Commenting on another tragic day had become a habit.”

To accompany the change of personnel, came a shift in style. Naturally, Cruyff – a three-time European Cup winner with Ajax – wanted to win, but there was a way of winning. A philosophy, an identity.

In the era of 4-4-2, the young manager introduced the 3-4-3 formation – an adaptation of the 4-3-3 system Cruyff had played under the coaching pioneer Rinus Michels for the Netherlands and Ajax in the 1970s.

“We couldn’t believe how many attackers were in the team,” Eusebio, who made more than 250 appearances under Cruyff, said of the day the boss first drew three defenders, four midfielders, two out-and-out wingers and a center-forward on the blackboard.

This radical change would require players to be comfortable interchanging positions. They would have to press, they would have to pass swiftly. Possession would reign supreme, which was not an easy task in a club where defenders were usually jeered for passing the ball back to the goalkeeper.

For Cruyff to implement this cerebral approach, he needed a production line to supply him with possession-hungry players. Cue the overhauling of La Masia, the club’s academy. Barcelona would never be the same again.

Differentiating Barcelona from the rest

Every team, from the under-eights to Barcelona’s B team, were ordered to play the revolutionary 3-4-3, with an emphasis on technique rather than physique, another volte-face for a club which, as recently as 1986, selected young players based on whether they would be taller than 1.80m.

First off the conveyor belt were Albert Ferrer, Guillermo Amor and Guardiola, the 1992 history-makers.

For Carlos Hugo Garcia Bayon, a former assistant coach at Barcelona B, winning the European Cup with academy graduates in the side was confirmation that Cruyff’s methods worked.

Bayon tells CNN: “It was that victory which changed the culture and mentality of the club. They won the European Cup, but won it playing a specific style and with a lot of players from La Masia.

“It was something unique, something that differentiated us from others.

“Without a doubt, if you have a methodology and that methodology doesn’t win, you are going to lose confidence to play players from the academy.”

From that famous Wembley win, other world class seedlings blossomed at the La Masia hothouse: Xavi, Lionel Messi, Andres Iniesta, Carles Puyol, Gerard Pique, Cesc Fabregas, to name but a few.

All of them, bar Messi, integral to not only Barcelona’s success but that of the Spain team which won the World Cup in 2010 and two consecutive European Championships in 2008 and 2012.

“They were the generation who paved the way for us,” says Xavi of the European Cup-winning Dream Team. “They gave Barcelona a winning mentality. It was an example for all of us.”

Hunter says academy players grew up “thinking anything was possible” after seeing the likes of Guardiola succeed on the biggest stage of all.

“The brand of football we saw from 2003-12, the unbroken stretch of success, those types of players, the promotion from the youth system, the attitude, the winning mentality, all of these have geneses in the Wembley victory over Sampdoria,” he says.

‘Now you have it here’

From Wembley to Barcelona and a dizzying week of celebrations for the club’s European pioneers.

On the balcony of Placa de Sant Jaume, stood Cruyff’s men, soaking up the adulation of their fans, holding aloft the European Cup. Fantasy had become reality.

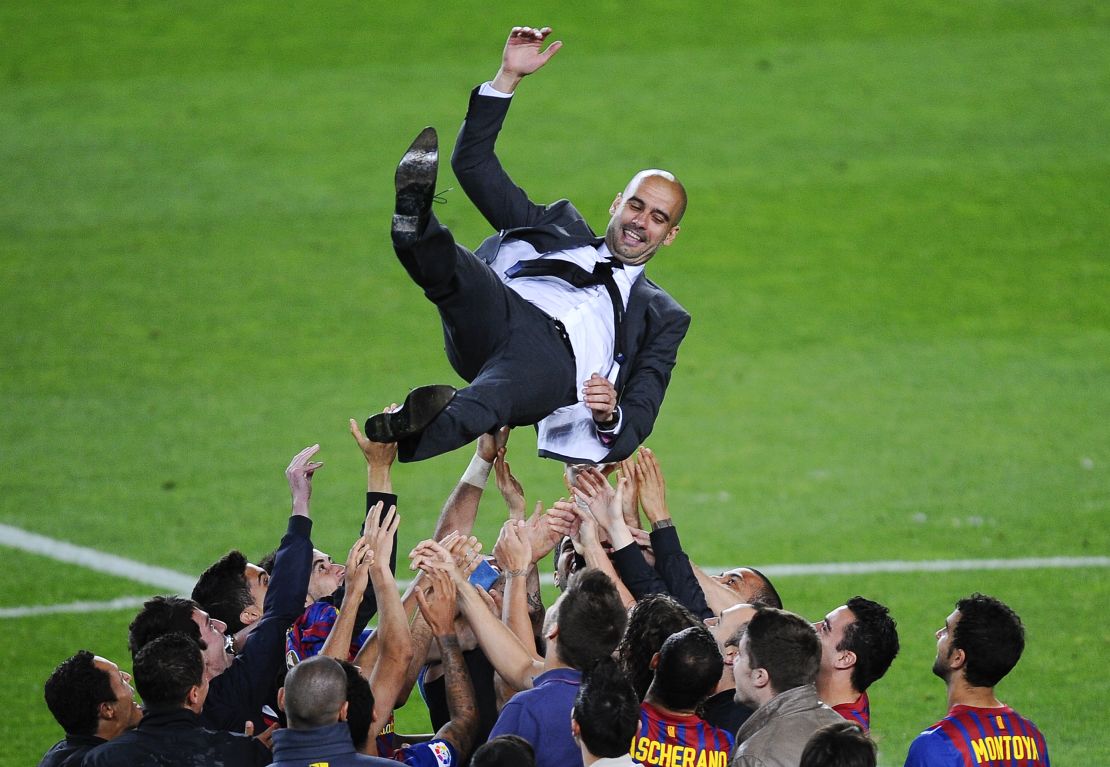

A 21-year-old Guardiola, the Catalan symbol, shouted: “Citizens of Catalonia – now you have it here.”

The midfielder, says Hunter, had prepared in advance, modifying a phrase used by Josep Tarradellas, named “President in absentia” by his people in 1954 during the Franco dictatorship, when on the same balcony in the city’s gothic quarter 15 years earlier.

The Dream Team’s European success, combined with the Olympic Games which was held in the city later that summer, transformed Barcelona and its people.

Hunter describes the summer of 92 as the “one of the most important summers in the history of Barcelona and Catalonia.”

The football club, whose slogan is ‘more than a club’ for its defense of the Catalan culture and language, became Catalonia’s most important institution. The radical shift was not solely on the pitch.

Spreading the Cruyff gospel

November 25, 2012, the day the teachings of Cruyff, his vision for a team full of La Masia pass masters becomes reality.

Barcelona is playing Levante in a league game. In the 14th minute Martin Montoya replaces Brazilian full-back Dani Alves. It is the first time in Barcelona’s history that the entire first team comprises of players who graduated through the club’s now famed academy. It is the legacy of Cruyff and the 1992 European Cup win.

“La Masia is a football school but also a school of values, a school of life,” explains Xavi.

“It is something to feel proud about. We now have 20 to 25 years of harvesting titles for Barcelona and playing an attractive style of football for the fans.”

Guardiola, the great player who became the club’s most successful coach, has often said that he and other Barcelona managers have simply been restoring, or improving, the chapel that Cruyff painted.

The Catalan himself created a football masterpiece, winning 14 trophies in four golden seasons between 2008 and 2012 with one of the greatest teams in history, the heart of which were other wordly academy talents.

For Bayon, currently academy director at Celta Vigo, the transformation of the Dream Team from playing greats to high-class managers is another lasting legacy of that 1992 win, with Cruyff’s former players spreading his gospel in various leagues around the world.

In England there is Guardiola at Manchester City and Koeman at Everton, while Eusebio is in La Liga. The latter two are being linked with succeeding Luis Enrique as Barca boss when he leaves at the end of this season.

There are others too: Michael Laudrup managing in Qatar, Txiki Begiristain, an unused substitute at Wembley, as sporting director at Manchester City and Andoni Zubizarreta in Marseille as the French club’s sporting director.

“They have become great managers, that’s one of the most important thing from that victory. It generated a culture of coaching. It is not only to generate great players, but great coaches,” says Bayon.

An identity changed

And so, to the future. What about the Barcelona of today?

Under Enrique, who will depart at the end of the season having won the Champions League and two Spanish titles, does the legacy of Wembley 1992 still run through the side like letters in a stick of rock?

Of the title-chasing Barcelona team which started in the 4-1 victory over Las Palmas on May 14, only four players – Sergio Busquets, Messi, Iniesta and Jordi Alba – had played for the academy. Alba, released by the club in 2005, was repatriated seven years later at a cost of 14 million euros ($15.49m) from Valencia.

Possession has not always been king for Enrique’s Barcelona, although there have been significant departures during the Spaniard’s reign.

Aged 35, Xavi left in 2015 to play in Qatar, following another academy great, Carles Puyol, who retired in 2014, out of the Camp Nou.

“No youth system will be able to produce that generation repeatedly on demand,” says Hunter. “It’s just not feasible, but the tail-off has been pretty dramatic and has inevitably changed the football Barcelona play.

“When you sign from outside they don’t have the same aptitude, they don’t speak the same football language.

“There are fewer youth products available to Enrique than there were to (Frank) Riijkard and Guardiola and it’s also been a strategic idea that the front three – Messi, Neymar and Luis Suarez – need to be given the ball more quickly and with less elaboration because they’re different strikers to any in the club’s history.

“They need less work, they’re able to score on their own so the midfield is sometimes bypassed.

“The identity of the first-team football in the last two-and-a-half years has significantly changed, but the actual existence of the youth system in unchallenged, it’s part of their identity.”

Who would make the cut in your Barcelona Dream Team? Have your say on our Facebook page

Ifs, buts, maybes

Is this the closing chapter of a glorious Cruyff-inspired quarter of a century of success? Not quite.

In Xavi, Pique, Busquets and Puyol, Barcelona could have former pupils as zealous off the pitch for their brilliance on it.

Xavi has already said he dreams of one day managing his former club and has divulged a plan which would have the club run exclusively by former La Masia graduates, with Pique as president, Puyol as sporting director and Busquets as his assistant.

READ: My dream is to coach Barcelona - Xavi

READ: Xavi unveils ultimate player

READ: ‘Messi is the greatest ever’

“If we talk in 10 years’ time, I imagine some president will have attempted, and succeed, in appointing Xavi as first-team coach, with Busquets as his assistant,” says Hunter.

“It’s Pique’s declared intent to run for presidency at one stage of his life. That would be the most dramatic induction of Cruyff and Guardiola values into the club.”

How different would Barcelona’s history be had they not won in 1992?

The trophy cabinet tells a story: Three league titles in the 25 years leading up to the Dream Team’s European Cup success, 13 thereafter and four nights of Champions League glory – a total of 44 trophies in 25 years and their status as one of the sport’s dominant forces fixed.

Pessimism replaced with confidence, fatalism defeated, and the club’s global status only reinforced by the style – dubbed tiki-taka – that accompanied that success.

Had Barcelona not won in 1992, they may have had greater motivation, Hunter argues, in the 1994 Champions League final against AC Milan, which they lost 4-0.

“They were complacent, they believed they would win for sure,” he says.

But without European success under Cruyff there is less glue to hold his system in place.

Visit cnn.com/tennis for more news and videos

“You can’t say whether they would have won other Champions Leagues because each of the Champions Leagues subsequently won after 1992 have direct lineage to Cruyff and his beliefs,” says Hunter.

“With no trophy under Cruyff then Barcelona’s history is subsequently going to be much poorer and the trophy cabinet is going to be more barren.

“No European Cup win under Cruyff and the subsequent history, which we’ve become so used to – the signing of Messi, the recruitment of Iniesta – probably wouldn’t have happened.”