This episode of “Fit Nation” will air on Saturday, April 22, between 1 p.m. and 6 p.m. ET, and on Sunday, April 23, between 5 p.m. and 6 p.m. ET.

Story highlights

One of the largest races in the emerging sport of snow kiting takes place on a remote, windy ice field

Like the legend for which it is named, few make it to the end of the snow kite competition

Snow kiting is as exciting as it looks. Speeds of up to 70 miles per hour. Leaping 80 feet up in the air and gracefully soaring distances as far as 500 feet before landing back on frozen terra firma.

Combining proven fun activities of skiing or snowboarding with kiting makes the joy exponential.

It’s also harder than it looks. The skills required are highly technical, the gear is complicated, you need to be very fit to be competitive, and it can only be done in certain regions of the world.

One of the best is Hardangervidda, a Norwegian national park that is the largest mountain plateau in northern Europe. The 3,000-square mile field is devoid of power lines and tall buildings and feels remote, but is just a majestic three and half hour drive north of Oslo. The wind is constant, the snow is more than 4 feet deep, even in the spring, and the terrain is a thrilling variety of open flat stretches, vertical hills and rocky obstacles.

If it reminds “Star Wars” fans of Hoth, the frozen planet from the opening of “The Empire Strikes Back” it’s because it was filmed nearby, on the edges of Hardangervidda.

And it’s home to a large annual snow kiting race called the Red Bull Ragnarok that, at 80 miles in length, is more endurance than speed race. It’s so difficult that of this year’s 350 athletes, only eight finished.

Ragnarok: Battle of the gods

Norse mythology holds that the final battle between the gods of good and evil was fought at Ragnarok. It’s a story they teach Norwegian kids in school. Like the legend for which it is named, few make it to the end of the snow kite competition of the same name. It’s a battle to the non-finish for nearly everyone who competes.

Race day starts with a gathering at the nearby Haugastøl Hotel. It’s only then that the location and course layout are revealed for the first time – they change from year to year. Everyone loads into buses, their skis, boards and kites packed in the luggage hold, and goes to the designated rig area.

This year, the temperature at the start was 2 degrees Celsius, just above freezing, but the winds were, as local organizer, Bjørn Kuapang, 31, says, “epic,” reaching up to 45 miles per hour. As with past years, the race day was postponed 24 hours for clearer skies and more wind.

Norway's snow kite race across the tundra

Some assembly is required. The snow kiters lay out their sails and lines in the snow and those with inflatable kites start pumping away. The vast assembly area resembles a colorful refugee camp, sans kids and poverty.

Then, by 11 a.m., they glided to a starting line that is about 800 feet wide. No megaphone would carry across that distance in that wind, so the start is signaled by flags: red (15 minutes warning), yellow (5 minutes), and green – sail!

The mass start makes for a beautiful panorama, like a flock of dayglow gulls against a near-white background, with huge cloud shadows floating across the course. At a distance, it’s as quiet and peaceful as watching a sailboat race from the shore. But up close, every one of the athletes is struggling to catch air and pull away from the pack, with many miles to go before they rest.

Of the 350 snow kiters this year, more than 200 were on skis, the rest on snowboards. They came from 29 countries; 60% from outside Norway. One guy was from Afghanistan. Thirty-three were women. Ages ranged from from teenagers (the cut off is age 16) to age 60.

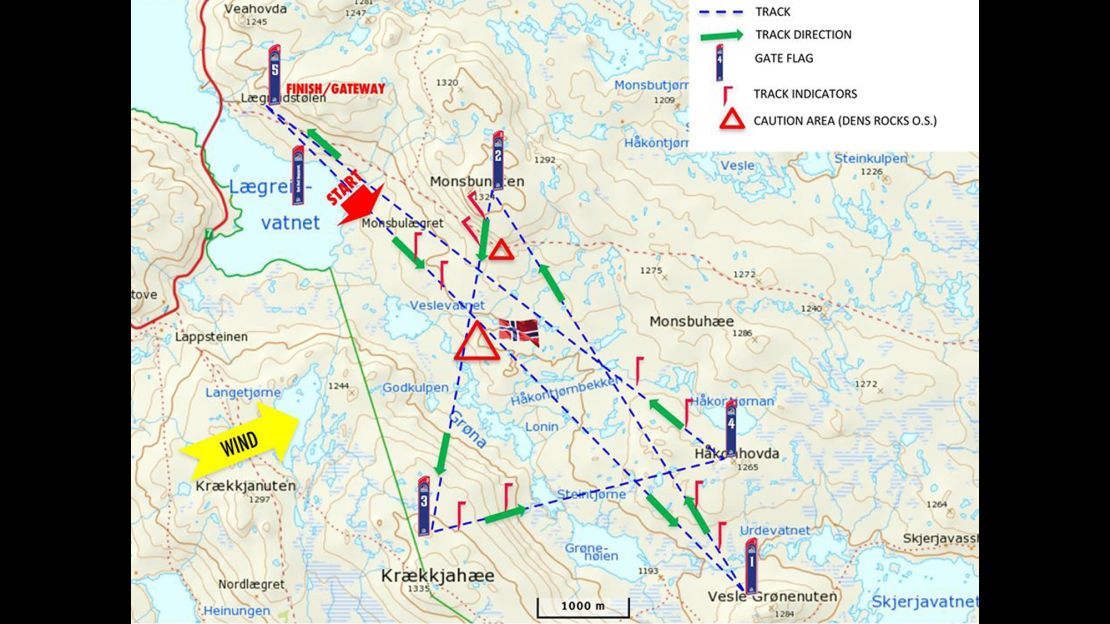

This year’s course resembled a stretched-out Star of David, criss-crossing the tundra through five gates. A huge red and blue Norwegian flag was planted in the middle as a visual reference point for the athletes who can easily get blown off course. You can’t see one checkpoint to the next, even on a clear day like this year’s race day. The finish line is at the fifth gate, after five loops.

Yet only about 2% of the racers will know what that experience is like. I asked Kuapang, why, if the race is so difficult to finish, was the length increased by 18 miles from last year. “It’s not supposed to be for everyone to finish,”was his matter-of-fact reply.

There are a number of reasons why so many don’t make it. Length is the main one. “People get exhausted,” explained Kuapang. The wind changes from a light breeze to gusts of up to 100mph, both of which tax the racers. They also have to maneuver around obstacles. Even those who have stamina can have technical problems with their gear that knock them out, and many timeout by failing to reach the final gate within the required five hours.

There are also injuries, although they’re rare. Hit a rock or another racer hard enough and you may be out of commission. One crucial rule of Ragnarok is that if you see another competitor in distress, you must stop to help them.

This year’s winner was Felix Kersten from Germany, who came in at 3 hours and 40 minutes. Of the 8 finishers, three were women. Kersten won more bragging right than money as the prize is around 15,000 Norwegian kroner, or about $175.

But win, lose or fall, most everyone ends up at the post-race celebration and awards ceremony at the nearby Haugastøl Hotel. It’s the only business in the local town of the same name, population nine. Awards are given, food is eaten, tales are swapped and the international wind-weary athletes promise to see each other at next year’s battle.

Superhero origin story

The race is located in the middle of Norway surrounded by snowy hills, icy lakes and homes so old they have grass on the roof and separate outhouses. The drive leading up to the race field is reminiscent of the Catskills in New York or the area around Lake Tahoe. Fifteen miles away is the modest resort town of Geilo with a large ski hill.

Haugastøl Hotel – where the hallway banisters double as ski racks – is a skier and snowboarder home away from home. Most of the racers stay there and between its location and snow kite school, it does a good snow kite enthusiast business all winter. Bikers flock to the area in the summer.

It’s also the Kuapang family’s hotel. He and a group of friends started snow kiting Hardangervidda a few miles away nearly 20 years ago. After several years on the freestyle circuit, one of them got a job at Red Bull, the energy drink manufacturer that has built an adrenaline- and Red Bull-fueled side business organizing various races.

The friends teamed up to create Ragnarok in their backyard. The first race was nine years ago, with 100 racers, and it has grown into one of the largest in the emerging snow kiting circuit. This year, all the spots filled up in 10 seconds after registration was open.

Inherit the wind

Snow kiting is highly technical and takes up to a year of regular training to master the basics. It’s like learning a language, explained Mike Kratochwill, a competitor from the Minneapolis area who owns a kiting business. “The learning curve is very steep.” And, Kuapang added, “There are no short cuts.”

It’s one of three power kiting sports that emerged since the 1970s. The first was kite buggying, which is a three-wheeled chair that people use to fly and leap off of beaches. Then came kitesurfing, which is a logical extension of the beach buggy. And then snow kiting, also called ice kiting, basically came from the same people who were already kiting on unfrozen water and sand.

All three sports use the same kind of kites, and enterprising folks have coupled these kites with ice skates, skateboards and kneeboards as well. Whatever the conveyance, you need a lot of space and a lack of power lines and other obstacles to enjoy yourself safely.

The geography of good snow kiting venues means a lot of travel unless you happen to live in Norway, Greenland, Canada, Russia, northern Italy, France or the US. Another expense beyond travel is the gear.

First, you need skis or a snowboard. The longer, straighter and stiffer these are, the faster you will go, but the harder it is for you to turn and therefore more taxing to legs and abdominal muscles. Then you need a harness, available in two types: waist or seat, which have straps under your legs. The choice of harness is personal comfort.

Then, there are clothes, and similar to downhill skiing, you’ll want ventilation and layers to prevent overheating, which can make you too cold from the sweat. Helmets are a must. Poles are a must-not. Everyone skis with a backpack of food and water.

The two most popular types of kites are inflatable tube and non-inflatable foil. It’s such a young sport that there isn’t universal consensus on which is better. Foil was once the norm, then tube became more popular and now foil is making a comeback. Kuapang said foil is harder to manage but faster. Pros tend to use foil.

For the Ragnarok, all kite types and harnesses are accepted, though kites can’t be switched out mid-race. If you have a mechanical malfunction, you’re done.

There hasn’t been a consistent international organization of snow kite racing. Kuapang explained that there used to be a federation, then it shut down and now a new one is in the works. Such is the evolution of an emerging sport. Red Bull has stayed independent of all the attempts at international oversight but has its own protocols for safety and standards for timing.

Let’s go fly a kite!

The surreal and thrilling pleasures and physical benefits seem to far outweigh the real but rare risk of twisting a knee or breaking a bone by running into a rock or another snow kiter. Spending time in nature has a proven wellness benefit and those who are dedicated to this sport, especially on a long endurance race such as Ragnarok, report peak experiences of being in the zone, and engaged at every level.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

The sport is also hard (or great, depending on your point of view) on the whole body, all at once. Harnessing the wind with a kite 100 feet in the sky with your arms and upper body, while simultaneously skiing or snowboarding with your lower body means a serious core workout of abs and back as well.

Legs often take the brunt. When it’s going well you can be in a squatting position for hours, which takes a toll. “If you’re not in shape, your legs won’t make it,” explained Shaun Hammargren of South Africa who now lives in Denmark. He made his third unsuccessful attempt at finishing this year. “And the more tired you get, the more mistakes you make.”

Training involves beingout on the snow as often as you can, but also weight training in the gym to build muscle for endurance rides. It’s not a particularly cardio sport, except for all the times you need to run to catch the wind gods. So try not to offend them.