Story highlights

"There are so many different recommendations, and it can be confusing," one expert says

There can be downsides to early screening, including overdiagnosis, some experts say

Despite what the American Cancer Society and other health organizations advise, many doctors still recommend routine mammograms to screen for breast cancer in younger and older women, a new paper suggests. Experts are divided on whether more screenings are beneficial.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends annual mammograms starting at 40 for all women, whereas the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends biennial mammograms starting at 50 for all women.

In 2015, the American Cancer Society updated its guidelines to recommend that women with an average risk of breast cancer have the option to start screening with a mammogram every year starting at age 40, and should undergo regular mammogram screenings starting at age 45.

In the new paper, many of the primary care physicians and gynecologists surveyed said they still recommended screening for women ages 40 to 44 last year. The paper was published in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine on Monday.

“All guidelines agree that discussions about mammography should begin at age 40. There is universal agreement on this age. Where the difference comes is the age at which screening should be recommended without the need for an informed decision,” said Dr. Richard Wender, chief cancer control officer of the American Cancer Society, who was not involved in the new paper.

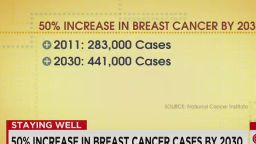

About 12% of women born in the United States will develop breast cancer at some time during their lives, according to the National Cancer Institute.

‘Ultimately, there is no perfect answer’

The new paper involved data on 871 primary care physicians and gynecologists in the United States who self-reported their breast cancer screening practices in a mailed survey from May to September 2016.

The data came from the Breast Cancer Social Networks national survey, which included physicians who were randomly sampled from the American Medical Association’s physician masterfile.

Overall, 81% of physicians who completed the survey recommended screening for women 40 to 44; 88% for women 45 to 49; and 67% for women 75 and older.

“Our results serve as a benchmark for breast cancer screening recommendations as guidelines continue to evolve,” said Dr. Archana Radhakrishnan, a researcher at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore and lead author of the new paper.

“Despite changes to guidelines, doctors are continuing to recommend routine mammograms to both younger and older women,” she said. “The recommendations varied depending on physician specialty; gynecologists were the most likely to recommend screening.”

Among the physicians in the paper who recommended screening, 62.9% recommended annual examinations for women 40 to 44, 66.7% for women 45 to 49 and 52.3% for women 75 and older.

“I trust the results of the paper. The response rate was high for a survey. The distribution of specialties was reasonable and clearly reported,” Wender said.

Dr. Mitva Patel said that she not only recommends annual screenings for women 40 and older, she follows those guidelines herself.

“I am 42. I have had my annual mammogram at age 40, 41 and 42,” said Patel, a breast radiologist at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, who was not involved in the paper.

She added that the American College of Radiology and the Society of Breast Imaging both recommend yearly screenings for women 40 and older.

“I put myself in patients’ shoes when I make a recommendation as a doctor, and I say, ‘this is what I would do for myself,’ ” Patel said. “There are so many different recommendations, and it can be confusing. So it’s important for patients to make their decision for screening with their primary care physician, and I’m encouraged that this study shows most primary care physicians still believe in annual screening starting at age 40.”

Guideline groups bring different perspectives and weigh different types of data differently, said the American Cancer Society’s Wender.

“Screening guidelines will constantly change in response to the emergence of new evidence. This is a good thing. As we learn more, we can refine guidelines based on new information. That’s why it’s important to keep updating guidelines. Groups are asked to balance the risks and benefits of a screening test,” Wender said.

“Ultimately, there is no perfect answer. Guideline groups must bring their own values into the recommendation. Breast cancer is a good example,” he said. “The risk of developing breast cancer steadily increases as a woman gets older; that makes it very hard to choose one starting age that is right for everyone. That is why shared and informed decisions in younger women are recommended by some of the groups.”

Why mammograms are a breast cancer debate

Neither the American Cancer Society nor the US Preventive Services Task Force recommend routine mammograms for women 40 to 44 because they are more likely to offer downsides than benefits, according to an editorial published alongside the new paper in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine.

Drs. Deborah Grady and Rita Redberg, professors at the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, co-authored the editorial.

Potential risk factors that can come with mammograms are overdiagnosis, in which a cancer that would otherwise never cause symptoms or death is found, and false-positive results, in which a patient could unnecessarily experience anxiety and take on the discomfort and financial costs of additional tests, such as a biopsy.

“One important issue is that payment systems in the United States typically reward ordering tests and procedures over taking the time to talk to patients about risks and benefits. The fear of litigation is often mentioned as a reason for unnecessary testing,” Grady and Redberg wrote in their editorial.

“Other excuses range from the influence of many decades of hype in the general and medical media, the idea that early treatment must be good, that knowing is better than not knowing, the allure of doing something rather than nothing, and the conviction that patients like more testing,” they wrote. “Limiting coverage of tests known to be harmful is a win-win for patients and the national health care system.”

Grady and Redberg pointed to the US Preventive Services Task Force’s recommendations to screen women 50 to 74 every other year as the appropriate guidelines to follow.

Dr. Andrew Kaunitz said he encourages his patients begin screening every two years at age 50, which is consistent with the US Preventive Services Task Force’s recommendations.

“There are many factors explaining differing recommendations,” said Kaunitz, professor and associate chairman of the University of Florida’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology in Jacksonville, who was not involved in the new paper.

“Clinicians are concerned that if they do not recommend starting screening earlier and they have a patient diagnosed with breast cancer at a young age, they may be sued,” he said. “Although the best evidence indicates the benefits of screening mammograms are in fact quite limited, breast cancer advocacy organizations have been vocal and effective in convincing the public as well as health professionals that screening mammograms have major unequivocal health benefits. This makes it hard to move away from recommendations to start screening early.”

Similar to the findings in the new report, a previous study found that 75.7% of primary health care providers reported screening practices in excess of those recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force. That study was published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine last year.

“From my experience, working with patients, most say that they want to catch the cancer early. They’d rather find out,” said Patel, the breast radiologist.

Although most breast cancers are found in women 50 and older, about 11% of all new cases of breast cancer in the US are found in women 45 and younger, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“These women who are diagnosed in their 40s, their cancer can be more aggressive,” Patel said.

Even if a woman receives a false-positive screening result, Patel said, the anxiety that woman may feel is often short-lived, and as for the risk of overdiagnosis, there seem to be conflicting data on how often breast cancers are overdiagnosed.

“Overdiagnosis is a difficult concept for clinicians and patients to comprehend,” said Kaunitz, who wrote a commentary in the journal OBG Management last month reporting that more than one-third of tumors found during breast cancer screenings represent overdiagnosis.

Some studies suggest that less than 5% of screened breast cancers are overdiagnosed while others suggest that more than 50% are overdiagnosed.

Screening guidelines ‘continuing to evolve’

“So, there’s a lot of talk about all these different risk factors, and some of these societies are placing more emphasis on one of these areas, whereas we should focus on saving the most number of years of life, which comes with early detection,” Patel said.

“Rather than emphasizing the negative aspects of screening such as cost, anxiety or overdiagnosis, we should focus on the most important benefit of early screening, which is early detection and the number of years of life this can bring to the patient,” she said.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Some experts argue that more research is needed to help inform recommendations.

“We are continually understanding more about breast cancer screening – about who should get them, the different age groups of women who really benefit from it and how frequently women need to have mammograms,” said Radhakrishnan, lead author of the new paper.

“The guidelines are continuing to evolve, and there is more similarity now between the American Cancer Society and US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines,” she said. “American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also reports convening a group to look at their own breast cancer screening guidelines. Amidst all of these changes, we need to make sure that both women and physicians are made aware of what the recommendations are.”